I have always loved Ruth Graham’s writing. She has an ability to go deep into a subject and describe what those involved experience and believe. She rarely editorializes and is remarkably fair to her subjects, even when they have been the object of some scorn. Her 2019 Slate story about former Cardinal Theodore McCarrick was phenomenal.

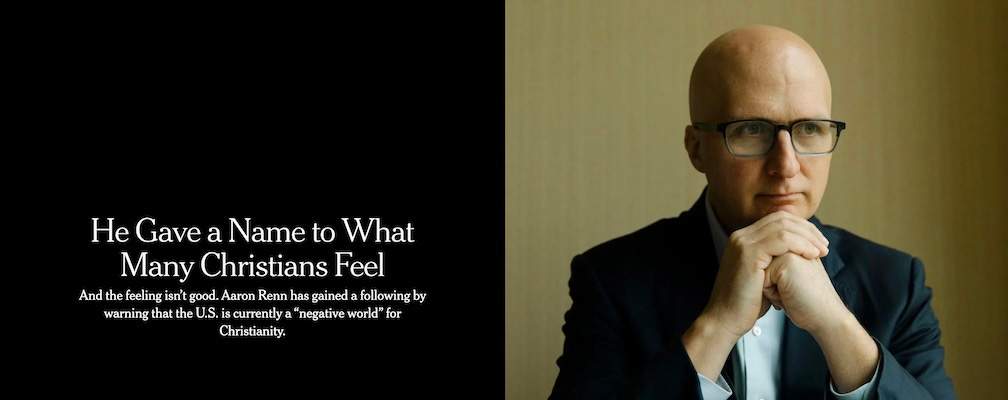

Ruth is now a religion reporter for the New York Times. Whenever I come across her work on social media, I stop to pay attention. Yesterday’s story on Aaron Ren caught my eye.

Honestly, what caught my eye were the references to Carmel, IN. Not only did I grow up in Indianapolis (immediately south of Carmel), but my son and family lived there until last August. So I knew the development and the safety and, mostly, those roundabouts.

Renn’s thesis is that we’ve seen a transformation in the relationship between (conservative) Christianity and the society at large. This is true as far as it goes, even if I’d likely characterize the shifts in different ways than he does. Here’s how Ruth describes it:

Mr. Renn’s schema is straightforward. Modern American history, he argues, can be divided into three epochs when it comes to the status of Christianity. In “positive world,” between 1964 and 1994, being a Christian in America generally enhanced one’s social status. It was a good thing to be known as a churchgoer, and “Christian moral norms” were the basic norms of the broader American culture. Then, in “neutral world,” which lasted roughly until 2014 — Mr. Renn acknowledges the dates are imprecise — Christianity no longer had a privileged status, but it was seen as one of many valid options in a pluralist public square.

About a decade ago, around the time that the Supreme Court’s ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges made same-sex marriage legal nationwide, Mr. Renn says the United States became “negative world." Being a Christian, especially in high-status domains, is a social negative, he argues, and holding to traditional Christian moral views, particularly related to sex and gender, is seen as “a threat to the public good and new public moral order.”

His first time period, pegged between 1964 and 1994, was when Christians were seen as having a positive impact on society. I probably would have begun this period in the late 1940s as mainline churches were seen as providing legitimacy to people in the public sphere. There’s different period post 1970 as mainlines decline and the evangelicals come on the scene (notably with the Moral Majority).

His second phase, the neutral world, falls between the early Clinton administration and the pre-Obergefell Obama administration. I’m struck that what he sees as the “neutral period” occurs at the time when evangelical leaders were accusing Clinton of drug-related murders and Obama of being a secret Kenyan Muslim.

To be fair, I haven’t read Renn’s book. And given Ruth’s review of where he has published and which other authors really love his argument, I’m certain that the ven diagram of his work/readership and mine is simply two circles.

The current period, beginning with Obergefell, is the “negative world”. He shares an example of how a church in Columbia, MO lost a popular film festival because the pastor espoused traditional views on gender. Tellingly, he blames this on “secular elites” and skeptics in the academy and corporate suites.

Ruth quotes a pastor in Wenatchee, WA who has started a podcast on the idea. I know Wenatchee a little as well. Suffice it to say that it’s not a hotbed of secularism and radical figures attacking conservative Christians.

It seems to me that the “negative world” is one where conservative evangelicals are expected to live within a pluralistic structure. They no longer have the luxury of believing their values are simple the default, “common sense” values. It means that if people feel your church is too restrictive (which you saw as traditional), they won’t support your film festival because the festival could be relocated.

As I was preparing to write this, I got Katelyn Beaty’s SubStack. She was responding to Rod Dreher’s new book, that draws heavily on Charles Taylor’s A Secular Age. Because Katelyn has more discipline than I, she has read Taylor’s book and offers a counter to Dreher’s interpretation. What she writes aligns with what I’ve said above.

When Christian authors claim that we’re living in an “anti-Christian” or “godless” age, they are speaking less to observable fact than to a perception of minority status and worldly hostility. That’s a visceral emotion, and boy does it sell books.

But when Taylor says “secular,” he doesn’t mean that most people are atheists now or even that they harbor anti-religious bias. Instead, he says, modern people now face a spiritual “supernova” of choices for faith, and that this plethora “fragilizes” the religious choices we make, knowing that we might have chosen otherwise, as do many of our neighbors.

I think when Dreher and other Christian writers hand-wring over our secular age, they are recognizing that Christianity is now one option among many, and that this fact creates unease. It means that we’ll likely meet neo-pagans, tarot card enthusiasts, UFO conspiracy theorists, worshipers of tech, psychedelics dabblers, and run-of-the-mill liberal agnostics who seem happy, fulfilled, and even sometimes more morally righteous compared with some devout Christians we know. It means that for every individual, there is a spiritual path perfectly tailored to his or her specific instincts and intuitions and context. Christians haven’t lost their seat at the table; they’re simply no longer sitting at its head.

While authors like Renn and Dreher (and scores of others) are writing about how society is downgrading religion, we’re watching an administration stop humanitarian aid by religious nonprofits and threaten religious groups who do refugee relief. The cabinet is full of conservative Christian influencers. The Supreme Court has taken up a case allowing a private religious school in Oklahoma to receive state funding.

Believing in a “negative world” may just be a marker of where you stand within the broader religious landscape.

There’s at least one reader who subscribes to both John’s newsletter and Aaron Renn’s (though I read John’s more than Renn’s) 😉 I read Graham’s profile and my two reactions were A) his negative world concept doesn’t reckon with the ways in which Christianity in this country earned a negative reputation and B) that I wish incredibly fair journalism like Graham’s was more celebrated and not just all demonized as the “MSM” But alas both of these phenomena are products of digital culture that for better and worse we see to be stuck with.

Good thoughts all around. I would make one stipulation that Renn’s framing is probably bad though. I think it’s better to look at religious culture in America as “institutionally protestant” for the first 100 years of our existence. church attendance was about as low as it is now, maybe lower, but there was an informal understand that religion was necessary for moral teaching, and our leaders were expected be church-going. The country was “culturally Christian” though disestablished. And then a bunch of catholics came over in the late 19th century. And suddenly Protestants got a little uneasy. And then world war 2 happened and the red scare, and we got richer and more culturally secular. That’s when Christians sort of came together and we saw the first waves of Christian nationalism (albeit minor to today) with “In God we Trust” as the motto, and with “under God” in the pledge. They incorporated those ideas because Christianity was no longer *universal.* those ideas were not incorporated in documents because they were assumed true, but not so much. The Public Square “bowling alone” christianity that we associate with American religiousity was really at its apex in the 50s and 60s. The religious rights influence over the last 60 years has grown on the right simply because they are losing power in the entire culture. Their apex has past. I don’t like the positive/negative framing, because I don’t think people actually view Christianity negatively, just *conservative Christian sexual ethics*. It seems better to look at the history of Christianity in America more as “universal disestablished” to “privately instituionalized” to “privately disestablished” today. Sorry for rambling!