Back on March 8th, the Senate acted with the support of President Biden to endorse a House resolution blocking the District of Columbia’s attempt to rewrite their criminal code. For nearly 20 years, the DC council had been working to review and update the district’s criminal code. The final product was approved by the council but mayor Muriel Bowser vetoed it, raising concerns about a potential rise in jury trials and reduced sentencing for carjacking (which has seen increased incidents in recent years). The council overrode her veto.

This is where the House of Representatives comes in. Since the 700,000 residents of the district don’t live in a state, they don’t have autonomy from the federal government. So the House has constitutional oversight, so they passed their resolution blocking the new criminal code from going forward. A Guardian report includes this quote from Speaker McCarthy:

“Many residents are worried about taking their kids to school or going to the grocery store. But rather than attempt to fix this problem, the DC city council wants to go even easier on criminals,” Republican House speaker Kevin McCarthy said in February, when the chamber’s lawmakers approved a resolution blocking the city council’s passage of the new code.

Let’s back up a second. The existing criminal code in DC dates back to 1901 and includes many crimes that are anachronistic (the Guardian mentions a ban on playing “Bandy”). The DC council started researching potential changes in the code in 2006.

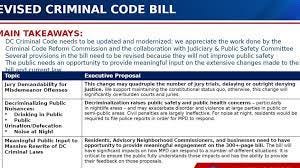

In addition to eliminating out-of-date offenses that were never charged the council wanted to align mandatory minimum sentences more closely to what judges in DC were actually doing. This is what brought about the supposed “easy on criminals” claim from the Speaker.

The Washington Post’s Perry Bacon served as an advisor to the DC council during their review. Here is Bacon’s description of their process:

Full disclosure: I was one of the two criminal law professors appointed by the council to the advisory group of the Criminal Code Reform Commission, which drafted the code. The other members included representatives from the U.S. attorney’s office, the D.C. attorney general’s office and the Public Defender Service. D.C. Superior Court judges and police representatives also attended many sessions, which were open to the public.

Of course, there were some pitched battles, and nobody got everything they wanted. The work took a long time — 51 meetings over almost five years — but we reached a consensus that resulted in the nearly 300-page proposed criminal code, which we unanimously presented to the D.C. Council.

Mayor Bowser’s concern that jury trials might strain the operation of the courts is valid on the one hand. On the other, the right to trial is constitutional and shouldn’t be shortchanged in place of guilty pleas just because it’s more efficient. (Even George Will agrees that plea bargains are constitutionally problematic!)

But the concern about going easy on carjackers is simply political posturing. As Bacon explains,

The proposed code reduced the maximum sentence for carjacking from 40 to 24 years. (Carjackers who use a gun could be incarcerated for 30 years, using the sentencing enhancement the code allows for gun crimes.) One of the group’s charges was to harmonize the criminal code with the actual practices of D.C. judges. We looked at sentencing records between 2010 and 2019 and found that for carjacking almost no one gets sentenced to the maximum. The average sentence is 15 years. It didn’t make sense to maintain 40 years for this crime when judges weren’t even locking up people for 30.

Our mandate also included making sure sentences are proportionate to offenses. Forty years meant that people could get the same sentence for carjacking as second-degree murder. The revised code punishes carjacking like most states (and for the record, more harshly than Biden’s home state of Delaware, where the maximum punishment for unarmed carjacking is 11 years).

There are at least two huge issues in the DC criminal code story. The first is this idea that reducing maximum sentences somehow is easy on criminals. If you heard that the penalty for unarmed carjacking was 24 years, would that seem lenient? Probably not — especially when it’s twice that of other states like Delaware. But if you’re told that it went from 40 years to 24 years, that makes it seem like something shifted even though judges were not using the lower level once mitigating circumstances were taken into account.

In the “Why Is This Happening?” podcast I referenced on Wednesday, host Chris Hayes got bonus points from me for citing Cesare Beccaria — an 18th century philosopher and jurist who created our modern understanding of punishment. He is thought to be the father of modern criminal justice. Beccaria argued that it was the certainty of punishment, and not its severity, that should be our goal. And if that punishment is to have some deterrent effect, it should happen fairly close in time to the actual offense.

So the whole reducing 40 years to 24 years claim is misguided. If the 15 years commonly sentenced (which is a lot!) doesn’t effectively deter carjacking, why would 24 or 40 or life?

The Brooking Institution announced a new initiative this week that is in line with Becarria’s philosophy. They suggest that the federal government use it’s funding streams to incentivize states and localities on efforts to lessen sentence lengths to more meaningful levels. Over the long run, they argue, it will reduce mass incarceration significantly.

I said that there were two huge issues in the DC council story. The second stems from the congressional assumption that DC is a crime-ridden hell-hole that can’t manage itself. Because it is predominantly a minority city and votes overwhelmingly Democratic, it becomes easy to scapegoat.

Just this morning, I saw a reference to an alarming statistic about the DC US Attorney. The National Review claimed that recent data showed that the USA only prosecuted one-third of arrests. They quote the opening from Law and Order, as if all crimes are prosecuted. The assumption is one of a “soft on crime” bias.

I looked up their reference. It is a document titled United States Attorneys Statistical Report for 2022. And if you go to Table 17, you can see that the USA declined to prosecute 52% of felonies and 71% of misdemeanors.

That’s all it says. There is no additional data presented as to why arrests were not prosecuted. In all likelihood it has to do with the quality of arrests and less to liberal prosecutors.

In addition, we have no context for what US Attorneys normally do. Because DC has this unique status as a district and not a state, it’s data appears in a table that includes no other jurisdiction. Evaluating the National Review’s claim would depend on knowing what USA’s do in all other jurisdictions. Perhaps prosecuting 1/3 of arrests is higher than average — we just don’t know.

At the end of the day, we have three issues with the criminal justice system in DC. First, the court system isn’t robust enough to allow defendants their constitutionally allowed jury trial. Second, a reliance on mandatory minimum sentences doesn’t really work as a deterrent. Third, we hold DC to standards not experienced by any state.

If you didn’t already think it was time for DC to become a state, this helps demonstrate why.