It was exactly two years ago tomorrow that I wrote about Jennifer McKinney’s excellent Making Christianity Manly Again. A content analysis of Mars Hill Church under the control leadership of Mark Driscoll, it used a sociology of gender lens to explore the culture of Mars Hill and the impact it had on members. I wrote:

Wait, you might ask, wasn’t there a whole podcast series on Driscoll and Mars Hill? Do we really need another look at what happened? The quick answer presented in Jennifer’s book is, of course we do. Because her book does many things that other excellent approaches have not.

For one, she puts the role of gender relations at the center of the Mars Hill experience. The misogyny present is not an unfortunate by-product. It was the brand. Who better than a gender sociologist to be able to unpack what happened at Mars Hill?

For another, she does a deep dive into content analysis. First, into Driscoll’s various sermon series and writings. Second, she uses interviews and online sources of Mars Hill members — those who loved it and those who couldn’t stay — to demonstrate the real world impacts of the Mars Hill masculine ideology.

Driscoll built the brand around the strong man imagery he felt was missing in Seattle. He critiqued modern men as “Cabriolet-driving, sweater-vest-wearing, Spice girls-singing wusses.” The Bible, according to Driscoll, required tough guys who like UFC and were willing to take strong stands for the faith. This would be the counter-cultural image that would change Seattle for Jesus.

I keep thinking that I need to write a SubStack post — or a series of posts — trying to make sense of the whole “crisis of men” argument. Sure, changes in macroeconomic structures have made life harder for men without college degrees. Or maybe the bro-culture around online video games and sports betting and crypto is about forming a new sense of belonging. Or maybe it’s a matter of stamping their feet because women are outpacing them and not “staying in their place”. Or because somehow calling out toxic masculinity among some (the Tate brothers?) gets splashed onto all (why would they be so susceptible, I wonder?).

I’ve come to see that I have seriously underestimated the challenges presented by the angry young man cohort. I was reminded of this when I listened this week to Ruth Braunstein’s new podcast, When the Wolves Came. In the first episode now out, she tells the story of two churches in Phoenix. One has set out to be a corrective to the influence of Christian Nationalism in evangelical churches. The other, though, is all in.

This second congregation had a very deep connection to Charlie Kirk and Talking Point USA. His organization has made great inroads among college campuses, especially young men. The militance of the church echoes the kind of “take it back” rhetoric from Kirk’s rallies (which often happen at churches).

By the way, perhaps it is no surprise that the “rehabilitated” Mark Driscoll now has a church in Phoenix and is taking the same stances he took in Seattle.

A post today in the Religion in Public blog written by my friend Paul Djupe and Brooklyn Walker made clear how serious all this is. They write about the elimination of the religious gender gap among young people. This is a combination of an increase in “nones” among females and an increase in participation among males.

To date, researchers are not showing the distinctiveness of the young religious men who are bucking expectations. For this we turned to a survey of Christians that we conducted in January 2024 (n~1500) that is weighted to resemble the national distribution of Christians.

Not only are young men equally or more likely to be involved with religion, but the nature of their involvement and commitments are distinctive. As shown below, young Christian men attend religious services more often than young Christian women and more often than older Christian men. But it’s not just showing up to church. This pattern repeats when it comes to religious involvement beyond worship, for which young men are involved in 2-3 more groups and activities than women – that’s 50 percent more. The differences do not end there as we also find that young Christian men have stronger Christian nationalist worldviews (measured using the Whitehead and Perry scale), and higher concentrations of apocalypticism (as measured by Djupe, Neiheisel, and Lewis). These gender differences are in the range of 10 percent among young adults and generally fade with age. Together they show younger Christians are more engaged with a very particular form of Christianity that seeks to exert control over the nation in part because they believe they are under siege by evil, demonic forces.

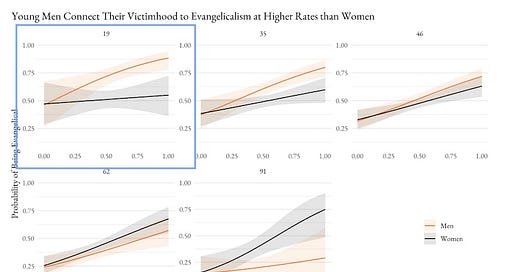

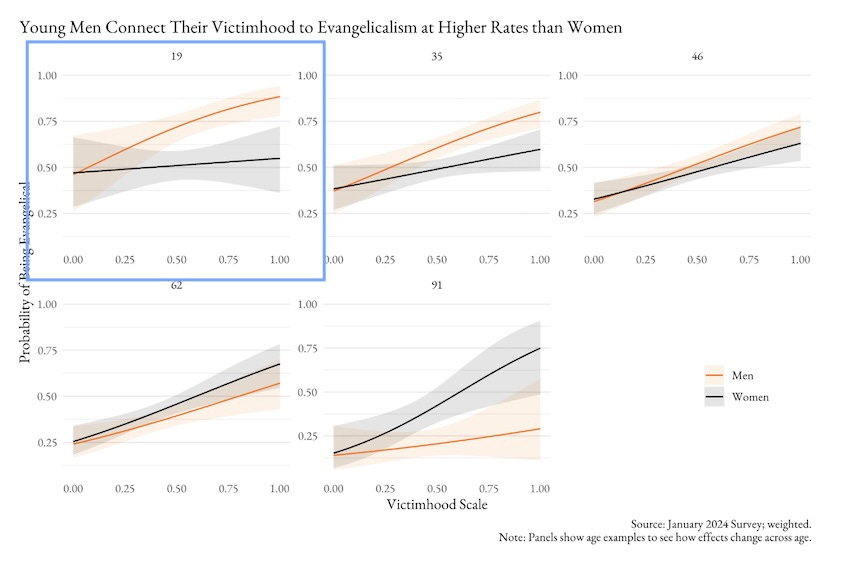

In a survey conducted last year, they examined the relationship between having a sense of victimization and the probability of being evangelical. They broke the relationship down by age and sex. The results look like this:

There is some interesting information here. First, the relationship between victimization and being evangelical is evident in the upward slope on most of the age categories. The exceptions are the very young women and the senior citizen men. But the slope for young men (in the blue box) is greater and their score on both victimization and likelihood of being evangelical are higher than the other age categories.

I want to be cautious about painting with too broad of a brush. As I said earlier, there are likely multiple factors feeding the so-called “crisis of men”. But a rise in militant, misogynistic, young men claiming the backing of Christ is a real challenge. Their influence of the rest of male youth culture could be huge and absolutely damaging to our social fabric.