Last week, Politico’s Alexander Ward and Heidi Przybyla released a story titled “Trump allies prepare to infuse ‘Christian Nationalism’ in second administration.” They write:

Christian nationalists in America believe that the country was founded as a Christian nation and that Christian values should be prioritized throughout government and public life. As the country has become less religious and more diverse, Vought has embraced the idea that Christians are under assault and has spoken of policies he might pursue in response.

One document drafted by CRA staff and fellows includes a list of top priorities for CRA [The Center for Renewing America] in a second Trump term. “Christian nationalism” is one of the bullet points.

While they admit that the documents they reviewed “do not outline specific Christian nationalist policies”, they do provide a review of past statements by Russel Vought, head of the CRA and his affiliation with William Wolfe, a proud defender of Christian Nationalism. Their story references recent comments from Donald Trump and Michael Flynn’s “ReAwaken America” tour.

Every time a story like the one in Politico appears, there is a very predictable response. First, there is a claim that nobody knows what Christian Nationalism means (more below). Second, there is the claim that this is a direct attack on people of faith, an affront to Conservative Christians everywhere who are being denied a voice. Then some will proudly take the label of Christian Nationalist, arguing that they are Christians who love their country. After the waters are sufficiently muddied, people leave the conversation behind until the next critical story appears.

I’ve been following this conversation ever since Andrew Whitehead and Sam Perry wrote Taking America Back for God: Christian Nationalism in the United States in 2020. Using data from the Baylor Religion Survey, they explored four broad approaches to Christian Nationalism. They differentiated between Ambassadors, Accommodators, Resisters, and Rejectors. They then examined the political, policy, and background correlates of the four groups.

Today, the Public Religion Research Institute released results of a detailed survey on Christian Nationalism. Their survey follows logic similar to that of Andrew and Sam. They have five critical questions:

The U.S. government should declare America a Christian nation.

Laws should be based on Christian values.

If the U.S. moves away from our Christian foundations, we will not have a country anymore.

Being Christian is an important part of being truly American.

God has called Christians to exercise dominion over all areas of American society.

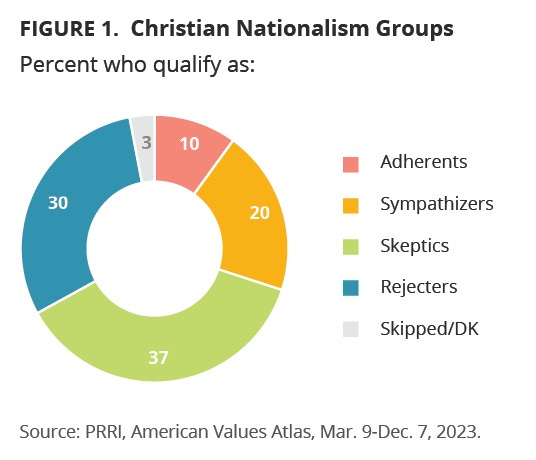

They measure agreement with these five issues to develop four categories. They label these Adherents, Sympathizers, Resisters, and Rejectors. The distribution of those four groups looks like this:

Roughly three in ten respondents are at least mildly favorable to Christian Nationalist sentiments, with a third of them being all in. As I wrote when Whitehead and Perry’s book came out, this sympathizers are important because they create a permission structure for the adherents. Because they hold milder versions of these, CN views, they can claim they are wrongly accused of extreme positions.

PRRI’s data examined various correlates with being either a sympathizer or adherent. They were more likely to be white evangelicals than mainline, a pattern observed by Ryan Burge last week. Ryan demonstrates that support for Christian Nationalism (using a different survey over time) had declined dramatically among mainlines and less so among White Evangelicals. PRRI found not only that Christian Nationalism was more predominant among Republicans, but that the aggregated state level support looked an awful lot like the red state and blue state maps that have become part of our political culture.

The data shows that thirteen states have over 40% adherents or sympathizers (in descending order): Mississippi*, North Dakota, Alabama*, Kentucky*, West Virginia*, Louisiana*, Wyoming*, Nebraska, Arkansas*, Tennessee, South Carolina*, South Dakota, and Oklahoma*. The nine states with asterisks have 17 percent or more of adherents (23 in Alabama!).

I find that separating out the adherents is a useful way to avoid the confusion (intentional or playacted) around what Christian nationalist goals really are. Alabama is an interesting example. The recent IVF decision by the Alabama Supreme Court declaring frozen embryos persons related to wrongful death litigation is a good case. On the one hand, we might have argued that this was simply a reflection of conservative pro-life positions. Yet the chief justice (who was a pal of Judge Roy Moore back in the Ten Commandments fight) filled his decision with quotes from the Bible (KJV) and theology. I learned during the PRRI webinar that right after the decision, he appeared on a podcast promoting Seven Mountain theology (where Christians should take control of the seven major institutional areas of society). Here’s David French:

But Christian nationalism isn’t just rooted in ideology; it’s also deeply rooted in identity, the belief that Christians should rule. This is the heart of the Seven Mountain Mandate, a dominionist movement emerging from American Pentecostalism that is, put bluntly, Christian identity politics on steroids. Paula White, Donald Trump’s closest spiritual adviser, is an adherent, and so is the chief justice of Alabama, Tom Parker, who wrote a concurring opinion in the court’s recent I.V.F. decision. The movement holds that Christians are called to rule seven key societal institutions: the family, the church, education, the media, the arts, business and the government.

French observes that not everyone who holds conservative christian values and policy positions is a Christian Nationalist. What is key is the notion of Christian supremacy to the exclusion of others. I’ve heard many commentators react to Speaker Mike Johnson’s claim that you can find his political ideology by studying the Bible on his shelf. Does that make him an adherent? I’d prefer to see him as a staunch sympathizer, who can offer legitimacy to the actual adherents. At least until his advocated policy position become more Christian nationalist than partisan. Mark Tooley of the Institute on Religion and Democracy tries to make such a distinction:

Christian Nationalism is distinct from conventional Christian conservatism. The former are typically post-liberals who want some level of explicit state-established Christianity. The latter have been and largely still are classical liberals who affirm traditional American concepts of full religious liberty for all. Both groups want a “Christian America.” But the former want it by statute. The latter see it as mainly a demographic, historical, and cultural reality.

I’m not sure what he means about that last sentence. Demographic and cultural change is what is fueling much of Christian Nationalism. Leaning on the history of a Western European Colonial tradition doesn’t provide the framework for dealing with today’s shifting pluralistic democracy.

Yesterday, Daniel Williams made this distinction clear in The Anxious Bench. He contrasted civil religion, as articulated by Robert Bellah in the 1960s, with Christian Nationalism.

In other words, Christian nationalism differs from traditional civil religion primarily in being anti-pluralist. Christian nationalists may be mostly correct about the historic prevalence of God in public life for much of the nation’s history. But their use of that history to try to reclaim the country from the secularists is at odds with the intention behind civil religion.

Nevertheless, political actors use vague phrases to prompt both sympathizers and adherents to action. When Jack Prosobiec told CPAC that he wanted to end democracy in favor of the crucifix he was wearing, that will signals adherents. When Donald Trump says that revival is coming, that preachers will have new power, and that he’ll stop “anti-Christian bias”, he knows that sympathizers will be excited and adherents will be motivated.

As we engage Christian Nationalism during this election cycle, it’s important to keep our focus on the adherents. They are engaged in a fundamentally anti-democratic process. The sympathizers give them cover when they take offense at some insensitive claim about Christians (think “clinging to their religion and guns”). The good news is that the adherents are only ten percent of the population, albeit a vocal and active ten percent. What we need to do is to mobilize the skeptics and rejectors and move some of the sympathizers into the skeptic column. That requires shining a bright light on what the adherents really want to accomplish.

Excellent.

Thank you .