Today I’m workshopping an idea from the third chapter of my book project on The Fearless Christian University.1 The focus of the chapter is pedagogy, curriculum, and intended outcomes for Christian University students.

Normally, I post these newsletters on MWF. I started prepping for this piece yesterday and then, frankly, chickened out. I thought that maybe my idea was too underdeveloped, too tentative, to share with the social media world.

But last night, my Westmont sociologist friend Blake Victor Kent shared on social media a student comment he’d received. It’s not my place to share specifics, but the student focused on issues of mentoring, character, and humility. The student comment was more in line with where I see chapter three heading than the traditional Christian Worldview and so here we are.

While the idea that Christian Universities should be different from their secular counterparts was part of the DNA of their founding, it took on a new quasi-intellectualism in the late 20th century. Francis Shaeffer’s How Should We Then Live? introduced evangelicals to a broader philosophical critique of the assumptions of the modern world. In her excellent book Apostles of Reason historian Molly Worthen writes of Schaeffer:

He deployed the trappings of academic investigation – litanies of historical names and dates, an accommodating version of Enlightenment reasoning – to quash inquiry rather than encourage it, to mobilize his audiences rather than provoke them to ask questions.

In 1999, Chuck Colson and Nancy Pearcey (a Schaeffer devotee) wrote How Now Shall We Live? to formalize the assumptions of the Christian Worldview over a wide variety of topics. Running over 600 pages, it mixes stories with strains of reformed theology. They describe the goal as follows:

Understanding Christianity as a total life system is absolutely essential, for two reasons. First, it enables us to make sense of the world we live in and thus order our lives more rationally. Second, it enables us to understand forces hostile to our faith, equipping us to evangelize and to defend Christian truth as God's instruments for transforming culture.

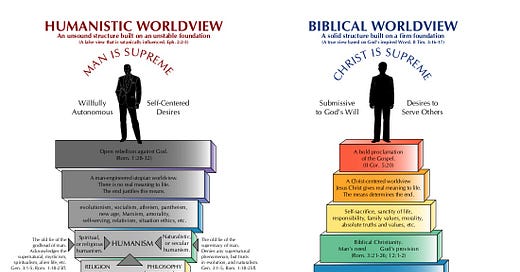

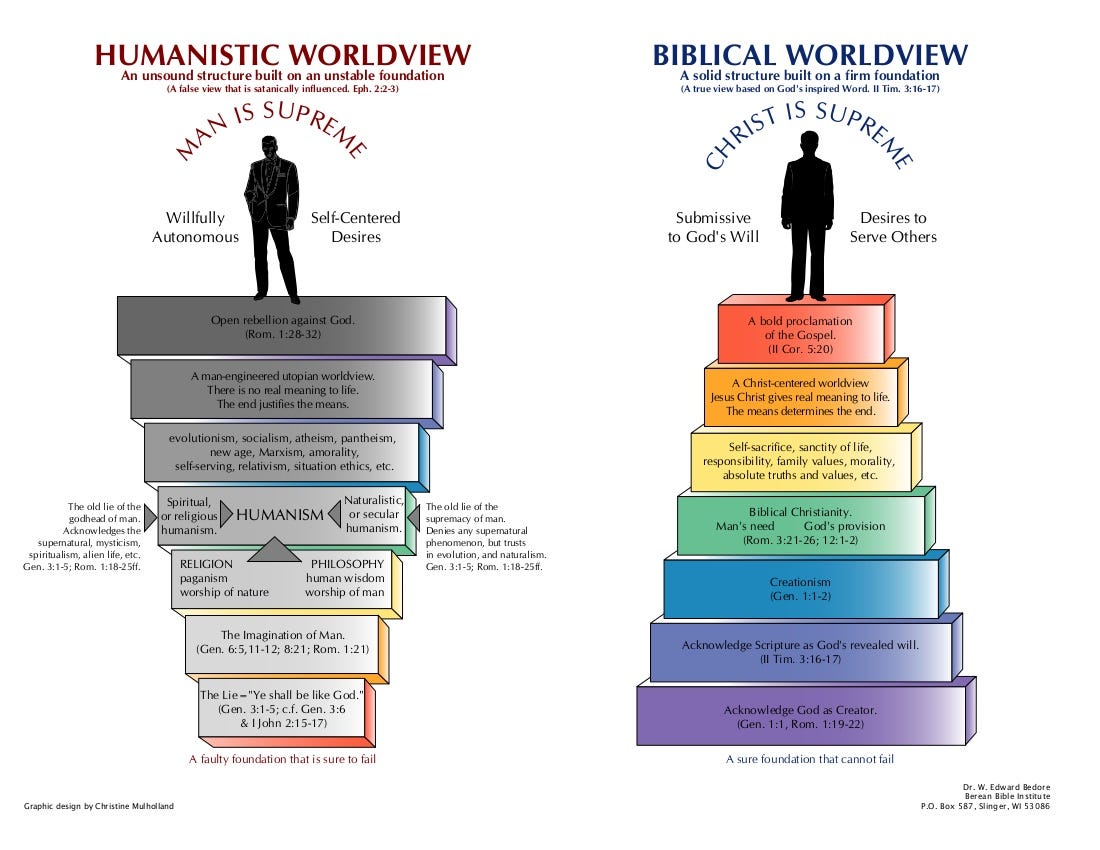

What stands out to me is that the second reason seems to be more of a guiding principle than the first reason. Consider the below graphic about Christian Worldview I found in Google Images.

It seems to me that the pyramid on the left (while overly general) has more specificity to it than the pyramid on the right. The one on the right builds on some scriptural passages with moral values thrown in.

In 2002, David Dockery and others at Union University published Shaping a Christian Worldview: The Foundations of Christian Higher Education.2 Dockery, then the president, solicited essays from a variety of faculty at Union.3 It starts with a set of introductory framing essays4 and then moves into discipline-specific essays. In his introduction, Dockery writes:

A Christian worldview is a coherent way of seeing life, of seeing the world distinct from deism, naturalism, and materialism (whether in its Darwinistic, humanistic, or Marxist forms), existentialism, polytheism, pantheism, mysticism, or deconstructionist postmodernism. Such a theistic perspective provides bearings and direction when confronted with New Age spirituality or secularistic and pluralistic approaches to truth and morality. Fear about the future, suffering, disease, and poverty are informed by a Christian worldview grounded in the redemptive work of Christ and the grandeur of God. As opposed to the meaningless and purposeless nihilistic perspectives of F. Nietzsche, E. Hemingway, or J. Cage, a Christian worldview offers meaning and purpose for all aspects of life.

Notice the primary focus of this paragraph. It’s not on the Christian worldview5 per se but on it as an alternative to all of the other flawed approaches in the contemporary world.

In the chapter, I argue that this approach to Worldview is the Achilles Heel of Christian Higher Education. Because the focus is on what lies outside the Christian University, the idea of what ought to happen pedagogically inside is underdeveloped.

There are several reasons why I argue that this approach is insufficient, at least without significant nuance. First, the student is too often a passive recipient of the contrasts between Christian and Secular Worldviews. They are too often introduced to the humanistic perspectives by the professor and then told how to refute those. It’s not a deep learning but something that goes along with being in a Christian University.6

Second, the very toolkit used in critiquing secular perspectives become models for how to examine implicit assumptions and interrogate alternatives. Four years ago I was working on a content analysis of seven millennial evangelical memoirists. Three of them explicitly credited their apologetics classes with teaching them how to deconstruct their faith.

Third, because the Christian Worldview is not integrated into the student’s self-understanding, it’s hard to see what happens after they graduate and leave the supportive surrounds of the Christian University. Once outside (based upon interactions I’ve had with former students) they are no longer thinking in these terms. It reminds me of one of my favorite passages in Peter Berger’s 1961 Invitation to Sociology: A Humanistic Perspective (yes I see it). He has a fascinating section on what he calls “alternation”:

Intensive occupation with the more fully elaborated meaning systems available in our time gives one a truly frightening understanding of the way in which these systems can provide a total interpretation of reality, within which will be included an interpretation of the alternate systems and of the ways of passing from one system to another. Catholicism may have a theory of Communism, but Communism returns the compliment and will produce a theory of Catholicism. To the Catholic thinker the Communist lives in a dark world of materialist delusion about the real meaning of life. To the Communist his Catholic adversary is helplessly caught in the "false consciousness" of a bourgeois mentality. To the psychoanalyst both Catholic and Communist may simply be acting out on the intellectual level the unconscious impulses that really move them.And psychoanalysis may be to the Catholic an escape from the reality of sin and to the Communist an avoidance of the realities of society. This means that the individual's choice of viewpoint will determine the way in which he looks back upon his own biography.

I would much prefer an approach to Christian pedagogy that builds from student experience, their coursework, their career dreams, and their faith and moves toward a coherent whole. Such a coherence would certainly serve the students for a longer period of time than our current process (which allows them to drop all this once they graduate, if not before).

Fourth, faculty members have already navigated these waters as part of their professional journey. A Christian faculty member moving through graduate education must decide what to exclude from the repertoire, what to reinterpret, what to accept. To ask them to rail at the boogeyman du jour will come off like a performance rather than a true engagement with the student and the material in question. Furthermore, this modeling of Christian intellectual character is key to developing the inquisitiveness we want in our students as they go on to become life-long learners affecting society.7

So this is where this chapter is headed. Once we move beyond the defensive stance against the secular worldviews, we can put our focus on where it should be: the learning of our students. Those students, for whom faith is a critical component of life, have a lot of questions about society, the church, the family, and themselves. We should centralize our energies on how to help them — through constructed curriculum, vital co-curriculum, and faculty/staff mentoring — to help them find an inculcated understanding of their place in the world.

I’m always glad to discuss this project with anyone who is interested.

I’m pretty sure that this was promoted widely by the Council for Christian Colleges and Universities. I had a copy on my shelf for years and know I didn’t buy it, so I’m thinking it was sent to me when I was an academic vice president.

Colson wrote the Foreword.

I have had personal conversations with two authors of these introductory essays who now believe that the Worldview language is not useful.

There is actually quite a bit of scholarship around what Worldviews are about and how a Christian approach differs from others. I’m painting here with a broad brush.

Over the course of my career, I knew many faculty who were assigned such classes. A few of them did take the approach I’m describing here. Most others found some other way to do it.

These latter concepts show up in a large number of Christian University mission and values statements.

I'm excited about your book project, especially (so far) this particular part of it.

Some thoughts, questions, observations:

1. Can Christians agree that there's no monolithic Christian worldview, and that the best we have to work with is the speech and actions of Jesus? The phrase "Christian worldview" smacks of "our American way of life." If Christians can agree on Jesus as the lodestone, then the Christian worldview is found in the gospels--whether one believes that Jesus was the Christ or not, even if one doesn't accept the relationship of the Old to New testaments as "promises made and promises fulfilled."

A secular Jew can have a more articulate and accurate Christian worldview than a myopic Lutheran. We certainly can't craft a cogent Christian worldview out of the behavioral history of the church. Sectarianism shattered it, which is ironic given how Christianity began in the context of the most religiously tolerant empire on the planet. Harvard is better at fulfilling its originally Christian charge now than it was when it started, paradoxically because of how hands-off its curriculum is about Christianity, and it's better at fulfilling that charge than is Liberty University.

2. What were, historically, provably, Jesus's speeches and actions? It seems the church lives in constant denial of how canonization has worked to form the Christian worldview, so how does a Christian college provide an ingenuous curriculum toward a recognizable weltanschauung? I think one healthy step toward a pedagogy of the Christian worldview is to recognize that it's an argument, neither a presupposition nor a destination. What if we made every student enrolled in a Christian college learn exegetical Greek, then told them that was only the lingua franca and not the Coptic and Aramaic and Hebrew they really need before they say Anthony Fauci only has a "worldview" on epidemiology just like they do? An increase in humility over territorialism, perhaps?

Will a Christian university demand of any argument that it be both sound and valid, regardless of whatever side brings it? That's the obligation of higher education to facilitate. Or, will we continue to support tracts of contention and the goal of "winning" over other positions even within the shared faith, as you've rightly pointed out has been too often the message of the ostensible Christian worldview? I mean, whatever we do regarding those "New Age secularists" (an oxymoron Dockery doesn't realize any more than he realizes who E. Hemingway was), let's never give them a seat at the table, because as one of my former pastors once put it, "We don't need to know what they believe. We only need to know what we believe."

The laugh I get when conservative Christian college groomers accuse liberal secularist professors of being groomers is gallows humor. It's not satisfying.

3. As soon as Christian colleges start hiring agnostics, atheists, at the very minimum a few ecumenists and members of denominations not in the direct feed to their schools, I think we'll start making a little faster progress toward a pedagogy representing a/some Christian worldview(s). How often have you seen this happen? Enough to matter? Let's put a Catholic on the board of Point Loma Nazarene, just to keep everyone's historical and liturgical facts straight, and not a rich Catholic, either. Some Franciscan who still eats at a subsistence level and lives in a studio apartment. That'll infuse the baccalaureate in business management (as well as the board meetings) with some Christian worldview.

4. Christopher Hitchens and Bertrand Russell understood the Christian worldview in ways that James Dobson and Paula White do not. By "ways," I mean that Hitchens and Russell actually understood it, given that it's not a church-as-rock anymore but a backpack full of rocks. Teaching Russell and Hitchens honestly is good for the doubt/faith relationship. Teaching against them as savages coming to burn the temple plays right into the hands of higher education's detractors. That's why Hitchens won almost every argument he took up despite his often patronizing, snarky tone.

5. The rocks in a backpack full of rocks wear each other smooth and sometimes mesmerizingly beautiful--we might say in accord--if you carry that backpack for enough miles and let the rocks mingle and work on one another. They get all bloody and broken when you throw them at secularists one at a time, Old Testament style. That backpack analogy comes straight from Taoism. Taoism really gets at the Christian worldview in ways that make non-Emersonian non-Unitarians fidgety.

6. Existentialism is one of the best doors into understanding the Christian worldview through which I have ever walked. To personify it: It doesn't care what Christianity thinks of it (Dockery misreads Nietzsche as adopting a "purposeless" position); consequently, existentialism has no desire to prove religion right or wrong, and to prove it "bad" would contradict at least the Nietzschean ideal; as an epistemology of handling the temporal with the sense that the eternal is horrifyingly unknown, existentialism respects Jesus's life and works more than many Christian epistemologies do; and it teaches us humor against despair. Christians have the hardest time with a sense of humor that isn't at the expense of other belief systems--many of which are at the roots of Christianity. I also prefer Sartre's existentialism, along with Hawkeye Pierce's, to Nietzsche's.

Those Sumerians and Egyptians are every Christian's progenitors, not enemies, along with what happened at the Nicaean councils and in Nag Hammadi. An honest curriculum and pedagogy toward a Christian worldview should teach students how canonization works--not just tell them that canonization worked. It should teach what myth is (i.e. that it does not mean "lie") and the functions of archetypes and forms. I think it should engage with the historical legacy of images toward the formation of spiritual practices, before and sometimes apart from religious institutionalization. I love that passage you quoted from Berger.

A good archaeologist would probably say there's no "worldview" to archeology except the one the archaeology as a profession inherits from its collective findings and vets as a community of scholars. The Hippocratic oath exists in medicine because patient care doesn't work so well when it's based on contention and opportunism. Christian colleges ought to have a "do no harm" clause in their mission statements, and they ought to share it in some attempt to universalize their worldview, at least for the purpose of higher education.

7. As far a curriculum goes, I learned as much about the Christian worldview in my quite secular graduate studies and through my own reading than I did from the formalized bachelor's curriculum of a Christian college. Maybe instead of lamenting that or blaming life-long learners for it, Christian colleges should embrace the contexts of their texts. That's how gestalts form healthily, even zeitgeists, but certainly worldviews. The groups that isolate themselves from the world, the ones that fail to reconcile faith with claim-to-evidence positions, those are just cults.

If a Christian college could set aside its ideological presuppositions and not sequester empiricism in the sciences, that would be remarkable. Students can usually tell which professors have already done this, so I think the more significant institutional impediments are the upper administration, board, and church. Who forms the Christian worldview" is, I think, as relevant a question as "What is it?"

A truly liberal curriculum and pedagogy of openness to ideas and compassion for others' experiences would set it apart from the elitism in secular institutions that conservatives often cite, an elitism that is, ironically and often, far more conservative than it is liberal. Think of teaching economics as a faith text (because it is!) and then demanding a prima facie case for the presence of the Epistle to the Colossians in the New Testament. Then we could explain the interdisciplinary, inclusionary nature of higher education by reminding everyone that Middleton gave Shakespeare (maybe even the Earl of Oxford) the witches for Macbeth.

The collegiate articulation of a Christian worldview should be better than the land-grant institutional articulation of it. At least the members of a secular land-grant school should have gathered any supportable articulation of the Christian worldview from their theological peer institutions. Do you think that's the current situation?

I think the same things about the poststructuralist cult in academia, which ironically faces the same problem you're tackling--trying to fit a problematic set of faith premises into a framework of knowledge. Postructuralism is in my view a near total failure, mainly because humanities academics who have embraced poststructuralist critical "theory" as "what we do" have also, as a friend put it, "written themselves into irrelevance."

Christian colleges have long been enabled by the anti-intellectual faction of the nation that wants to see its decidedly non/anti-Christian ideology accepted as Christian. It seems to me that a Christian college's attempts at articulating a Christian worldview isn't up against the argument of its possibility. It's up against the manipulation of the Christian worldview into irrelevance by fundamentalists and opportunists, who will sabotage any premise that would establish a pedagogy their club would deny admission. Is it possible to do for the Christian worldview what John Dewey did for progressive pragmatism in education?