While many good things happened during the Clinton Administration (and some bad things like abuse and impeachment), the legacy of triangulation modeled by the Democratic Leadership Council has continued to haunt our political environment. The attempt to move to the middle and embrace anti-crime/expanded law enforcement effots led to an inability to critique the current system and allowed Republicans to 1) ratchet up their commitments to law enforcement (and ICE) and 2) continue to claim Democrats don’t care about crime. Similarly, agreeing to work requirements for welfare only managed to set a baseline that Republicans could build upon, as we saw in the Big Beautiful Act.

But the thing that has perhaps had the biggest impact was Clinton’s desire to shift economic focus from workers to finance. His measure of success, which landed us a surplus for a few months before Bush squandered it, was the insure the healthy growth of the bond market and the financial industry in general. Bob Woodward explained the case in The Agenda, released in 1994.

Rather than taking territory from Republicans’ favorite talking points, the move to financial markets (as opposed to real markets) has played into the hands of those Republicans from Romney to now talking about the “job creators”. Simultaneously, it got working class voters asking if there was really a difference between the two major political parties.

As part of his series on economic inequality, economist Paul Krugman addressed how financialization has changed the nature of our economy in ways that are not helpful. He asks (full piece in paywalled):

The extraordinary growth of the share of US GDP accounted for by the financial industry raises two related questions. First, what are all these overworked but highly paid people doing? Second, is what they’re doing productive for the economy as a whole?

Krugman continues:

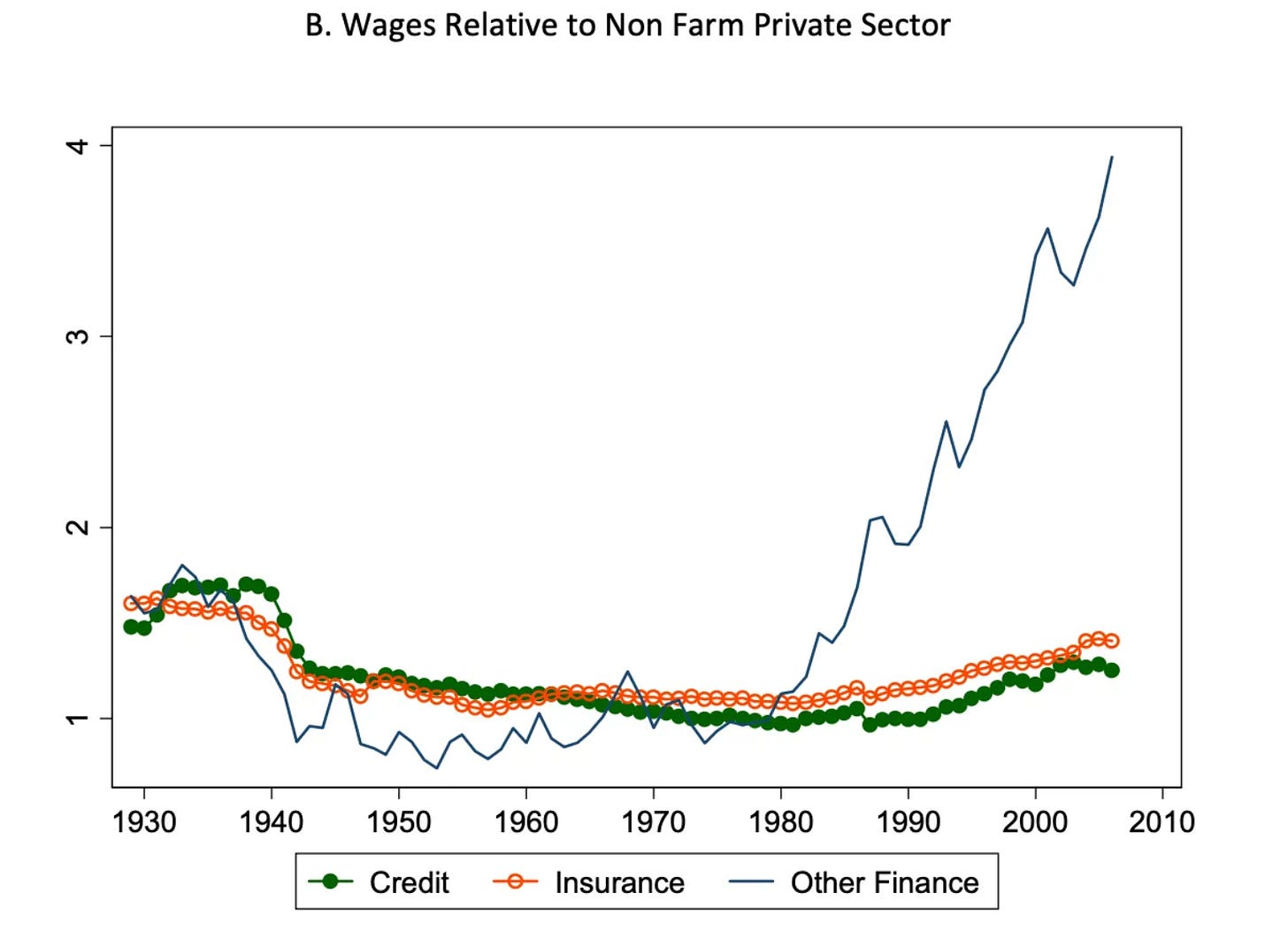

After 1980, however, earnings for employees in finance began soaring, more or less in tandem with the rising share of finance in GDP. This surge mainly took place in the more exotic parts of finance — that is, earnings in insurance or ordinary lending didn’t take off, but earnings in the activities we usually mean by “Wall Street” did. Philippon and Reshef have a nice chart making this point. The left axis shows the ratio of compensation in financial sectors to compensation in the nonfarm private sector as a whole:

He goes on to report that betweene 1996 and 2014, 35% of the wealth growth in the US came from the financial sector. And 41% of new billionaires over that period were the finance area.

The unique role of this sector of the economy came clear to most of us in the aftermath of the Great Recession. Creative financial instruments like Credit Default Swaps seemed to lie at the heart of the crisis. If you haven’t watched The Big Short, do so now. Even the players didn’t really know how these innovations worked, beyond the fact that they made lots of money. Regulators, lawmakers, and credit agencies were in the dark about the impacts. Those in the finance sector, at least those willing to take risks, could move faster than the watchdogs. And it’s real people who lose.

Back in 2018, I read Brian Alexander’s Glass House. It told the story of the Anchor Hocking glass factories in Lancaster, Ohio and what happened when the company was taken over by private equity firms who didn’t know anything about glass but were looking to find ways of increasing value for their stockholders. They and their beneficiaries did well. The town of Lancaster was never the same.

Brian followed that book with another three years later: The Hospital. It told the story of a community hospital in Bryan, Ohio, just a few miles from the Indiana line in Northwest Ohio. The hospital tried to serve its population well, many of whom were on Medicaid. But it faced increasing competition from larger chain hospitals and eventually absorbed into them.

Both of Alexander’s books contrast the stories of real-live people in small-town Ohio with the cold, analytic views of the finance titans. Both books read as tragedies and serve as an indictment on our economic systems. Trump won the counties for Lancaster (by 6%) and Bryan (50%) in 2024.

Given my interest in this topic, I was pleased to read Megan Greenwell’s new book, Bad Company: Private Equity and the Death of the American Dream. She tells the stories of four individuals and how their situations were devastated by private equity firms. In each case, a financial entity like KKR, Bain Capital, or Alden Global took over their company. This was accomplished, as was the case for Anchor Hocking, by leveraging debt. The predatory financiers loaded the company (not the PE firm) with the debt needed to buy the enterprise. Then they proceeded to bleed the operation dry, sell its property out from under them, and slash staff.

She tells the stories of Liz, who worked at Babies R Us in Tigard, Oregon; Roger, who was a leader at a small Wyoming hospital; Natalia, who was a journalist for a number of newpapers, largely in Texas; and Loren, who was a resident in a large apartment complex in Alexandria, VA. While the circumstances, industries, and locations vary, the patterns are very similar. There was a period of excitement with a job or hospital or vocation or residence. Then the private equity firm took over. Things don’t fall apart all at once, but a slow slide is evident and appears irreversable.

One of the surprising things about Greenwell’s book is that the last section is all about people pushing back. Each of her subjects land on their feet and wind up becoming activists in the process. Roger has put together a group that is trying to privately fund a new community hospital. Liz and Loren are activists in their own right, trying to bring light to what happened. Natalia winds up workign for a voting rights public journalism outfit shaping things in her home state in ways that local newspapers find difficult.

As encouraged as I was to see how these four turned out, I’m left with the sense that there is something very wrong with this situation. Why, for example, aren’t the private equity firms required to carry their own debt? Why are these “carried-interest” benefits taxed at lower rates? Why don’t we see that these firms, while ideally benefitting their shareholders, aren’t contributing to the overall economic well-being of society? I’ll close this post with a couple of paragraphs from Greenwell’s conclusion chapter:

Regulating an industry with so much power and wealth would require massive willpower, and willpower can be very hard to come by when it comes private equity. A committed lobbying operation and generous donations to politicians of all political stripes have helped protect the industry’s ability to operate largely unchecked; even support from both Donald Trump and Joe Biden wasn’t enough to close the carried-interest loophole.

Ordinary people, though, don’t benefit from those industries donations. And while support for private equity unites Republican and Democratic politicians, anger abotu wealth inequality and the disproportionate power of the ultrarich increasingly unites all Americans. (236)

There seems to be a never-ending supply of thought pieces on what Democrats should do looking toward the 2026 midterms and the 2028 presidential elections. I don’t think a Bernie Sanders strategy of attacking billionaires is the way forward. Some of those billionaires contribute to our overall economic well-being. But taking on the lack of oversight that allows predatory finance figures to destroy major segments of the economy seems like a good place to begin.

This. This is certainly a part of what's wrong with our economy and therefore our society. Thanks, John.

For me, crypto is another step removed from reality, and I'm amazed that some financial experts now say that ordinary people should hold 25% of their investments in crypto. So far as I can see, crypto provides nothing to our society in terms of real production.

And I think REITs should be regulated, too. In some cities, 20–25% of the housing is tied up in REITs, which contributes to our housing crisis, which end up being rentals that are generally not maintained the way that a home-owner would.

But regulation is one of the dirtiest words in the political vocabulary. Discouraging.

Motivating summary. I just put the book on hold at our (public) library!