On Monday of this week, the Internal Revenue Service reached a proposed agreement in a lawsuit (still must be approved by the judge) that modifies the understanding of the Johnson Amendment to allow pastors to endorse candidates to their congregations. It may be a meaningless change. Or it may create all kinds of havoc.

As a refresher, the “Johnson Amendment” refers to a 1954 amendment then-Senator Lyndon Johnson made to an IRS reauthorization. His move banned non-profits (501c3 organizations) from advocating for political candidates. President Trump railed against this amendment as stifling the views of Christians and put forth executive orders in both terms to block its enforcement when it comes to churches.

It’s worth noting that there has only been one major case back in 1999 where a congregation lost tax exempt status for political activity. In that instance, a congregation had taken out a full-page ad opposing President Bill Clinton.

The current lawsuit had been filed by two Texas pastors and an association of religious broadcasters. As David Fahrenhold points out in the New York Times, the original suit had much broader aims.

The plaintiffs that sued the Internal Revenue Service had previously asked a federal court in Texas to create an even broader exemption — to rule that all nonprofits, religious and secular, were free to endorse candidates to their members. That would have erased a bedrock idea of American nonprofit law: that tax-exempt groups cannot be used as tools of any campaign.

Instead, the I.R.S. agreed to a narrower carveout — one that experts in nonprofit law said might sharply increase politicking in churches, even though it mainly seemed to formalize what already seemed to be the agency’s unspoken policy.

The agency said that if a house of worship endorsed a candidate to its congregants, the I.R.S. would view that not as campaigning but as a private matter, like “a family discussion concerning candidates.”

I’m not sure what “a family discussion” looks like in a megachurch, but I’ll let that go for now. At the very least, an endorsement from the pulpit of a particular candidate would have some coercive effect on congregants, encouraging them to comply, stay quiet, or find another church.

A Nothing Burger

As congregations have been sorting themselves politically for years, increasingly over the last decade, the notion of endorsing a candidate may not be a big deal. It’s not like there haven’t been workarounds for years. Ralph Reed and the Christian Coalition were behind “voters guides” that laid out how Good Christians ought to vote (Pro-Life, Small Government, Strong Defense, Traditional Marriage, Low Taxes, Strong Defense). So naming the favored candidate is a small step making explicit what everyone knew was implicit.

As the Washington Post observed, even though actions against congregations were rare, it made for a great talking point. Organizations like the Alliance Defending Freedom have advocated for defiance of the Johnson Amendment.

The IRS rarely enforces the rule. Starting in 2008, thousands of pastors joined an activism effort called “Pulpit Freedom Sunday” to test the ban by endorsing political candidates during their sermons. The IRS investigated one but did not punish anyone in that case, according to the group that organized the effort.

Even before Covid, many congregations were regularly advocating for Republican initiatives, especially the reelection of President Trump in 2020 and 2024. Apostolic Prophets shared the prophecies God gave them about a triumphant Trump returning to office. Other conservative pastors, like Greg Locke in Tennessee were ubiquitous on social media with angry rants denouncing liberals (sometimes as witches).

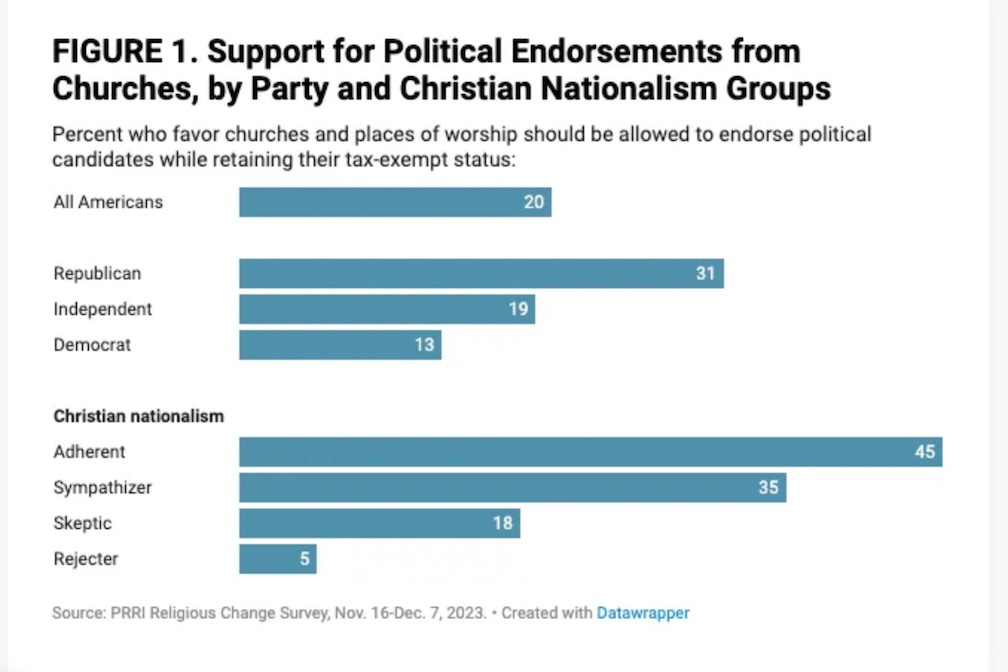

Congregations and pastors steeped in Christian Nationalism will feel further emboldened but the proposed IRS agreement, although they never showed any reluctance under the present circumstance. While according to PRRI, most people regardless of political party oppose pastors endorsing candidates, strong advocates for Christian Nationalism are much more favorable. Just under half of the Adherents favor political endorsements. The Pew Research Center has similar findings.

So, it’s quite possible that this proposed agreement supported by former auctioneer/congressman and now IRS Commissioner Billy Long may not make a lot of difference. Most congregations will be reluctant to have their congregation officially endorse candidates and frown upon overly partisan comments from the pulpit. The conservative firebrands and Apostolic Prophets will continue to do their thing knowing that the IRS isn’t coming after them (which it wasn’t doing anyway).

It’s a Trap!

On the other hand, I’m quite suspicious of how this new-found freedom will work when clergy or congregational endorsements run counter to the current administration. Will the IRS’s openness to “family discussions” work when the congregation is encouraged to vote for the Democratic candidate for Congress in November of 2026?

The Washington Post story cited above includes a quote from Doug Pagitt, executive director of Vote Common Good.

This is an important opportunity for liberal-leaning faith leaders who have held back from speaking out about political candidates while their conservative counterparts plowed ahead, said the Rev. Doug Pagitt, executive director of Vote Common Good, a liberal faith-based organizing group.

“We view this as a significant opportunity for Democrats to engage faith voters en masse. ... This change opens the door for more honest, values-based conversations in faith communities across the country,” Pagitt wrote in a statement. “Democrats who care about justice, compassion, and the common good should not shy away from this moment.”

A different story in the New York Times focused on the political stance of faith groups in New York City. The author noted that one could probably predict stances taken by Catholic parishes or Mosques in terms of abortion or support for mayoral candidate Mamdani. It then quotes a Reformed Jewish rabbi:

In a statement, Rabbi Jonah Dov Pesner, the director of the Religious Action Center of Reform Judaism, said the I.R.S. decision was bad news for houses of worship because it could wreak havoc on the lives of their communities.

First and foremost, he said, the decision introduces explicitly political debates into the religious life of a congregation that is supposed to be a place of refuge and spiritual shelter for all its members.

The decision also creates an opportunity for politicians to persuade a house of worship to endorse them by making a donation, which could then be portrayed as a tax-deductible charitable contribution.

But what happens when those Catholic parishes take a stand against candidates that support the administration’s immigration raids? Or an Imam critiques Israel’s heartless attacks on Gaza, Lebanon, and the West Bank? Will that be seen as “family discussion”?

It’s hard for me to be optimistic given the way the administration is currently treating international students who criticize US foreign policy or Catholic organizations advocating for humane treatment of undocumented immigrants. Do I really think that the administration will see those as “deeply held religious beliefs”?

As has been the case with this administration and this Supreme Court, I’m afraid that conservative Christian views are welcome from the pulpit and don’t threaten the church’s tax exempt status. But other groups may need to be wary. It’s not a stretch of the imagination to see those non-conforming religious groups become the subject of Truth Social screeds, AG Bondi press conferences, and over-the-top Fox News coverage.

Thank you

These are quite helpful thoughts, John. Thanks!