It’s easy to see where talking points come from. Anecdotal items come to be seen as patterns. News reports start connecting the dots between the anecdotes and describe a trend. Pollsters ask people if they are concerned about the trends. Politicians point to the polls to argue that people want something to change and critique the party in power for not doing something about the issue.

Data has a remarkable way of complicating political talking points. When we step back and reflect on what the data tells us, things are never as clear as the talking points suggest.

I was reminded of this while scrolling Twitter on Tuesday. Two different threads provided a very interesting perspective on crime and immigration, topics I’ve written about in this newsletter.

John Pfaff, law professor at Fordham and author of the excellent book Locked In analyzing mass incarceration, had this tread about the Department of Justice’s release of the 2021 National Criminal Victimization Survey (NCVS). Matt Soerens, US Director of Church Mobilization for WorldVision, had this thread explaining “apprehensions at the [Southern] border”. Both arguments deserve some unpacking. I’ll start with the crime data and then turn to the immigration data.

In late July, as part of my series on criminal justice, I wrote this piece on the FBI’s “Crimes Known to the Police” also known as the Uniform Crime Reports (UCR). As I explained, this report is created through the voluntary submission of data from localities to states and from states to the FBI. It allows a summary of both incidents and rates per 100,000 population for different categories of crime.

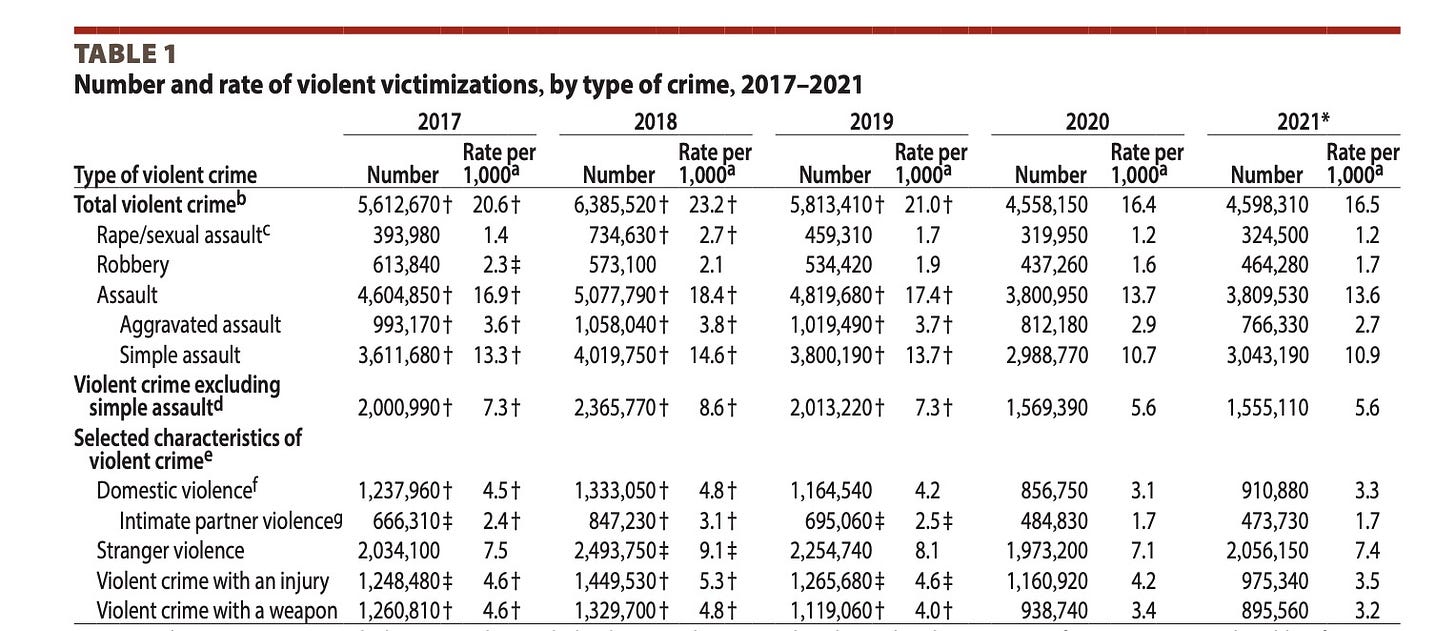

The NCVS is a national survey that asks people if they’ve personally been a victim of a violent offense or if their household was victimized by a property offense. Like the UCR, data is broken out by category within each of these broad classifications.1 Here is the top line data for violent crime.

Let’s first look at the incident numbers. I want to focus on the “violent crime excluding simple assault” line. Simple assault can include a scuffle outside a bar or domestic violence or some forms of road rage. These can be traumatic but aren’t what we think of as violent crime.2 The NCVS data shows that violent crime increased from 2017 to 2018 and then has fallen ever since. Notice that the NCVS estimates its crime rates as amount per 1,000 where the UCR uses amount per 100,000. What the NCVS rate tells us is that 5.6 people per 1,000 were victims of violent crime. In percentage terms (out of 100) that’s a 0.56 probability of being a violent crime victim in 2021. Pfaff correctly observes that the violent crime rate (and incidents) were relatively stable between 2020 and 2021 even though we were all staying at home in 2020.

In addition, Pfaff points to a part of the report where respondents were asked if they reported their incident to the police. Using the same “violent crime excluding simple assault” line, the percentage involving the police increased from 49.3% to 52.2% between 2020 and 2021. This is roughly consistent with the historic data showing that only half of offenses are reported. But if 3% more people report their offenses to the police, that will have a direct impact on the UCR and the overall violent crime rate will appear higher.3

This should in no way be seen as minimizing our concerns about the amount of gun violence occurring, especially in urban areas. It’s quite likely that we are seeing patterns of repeat offenders and repeat victims. But even with that, it suggests the need for much more caution when politicians and media figures talk about “fear of crime”.

Last Friday I wrote about Gov. Ron DeSantis’ stunt sending Venezuelan asylum seekers to Martha’s Vineyard. Stories about this strange plane trip from Texas to Florida to Massachusetts kept referring to those transported as “migrants”. DeSantis had apparently used laws that gave him some financial discretion about people in Florida “illegally” and how they could be moved out of state.4

Matthew Soerens’ thread on Tuesday began by acknowledging news reports claiming that “for the first time ever, 2 million people crossed the border illegally.” In fact, as he explains, there have been two million “encounters” at the border. But not all those crossed illegally. There are repeat encounters in the totals. This means that people “encountered” officials from Customs and Border patrol. It does not mean that 2 million people crossed the border and are now roaming freely throughout the United States.

He goes on to describe “border crossers” as those who had no legal reason to be here and entered between points of entry.5 But the Border Patrol's own numbers show that they have been doing an excellent job of interdicting those crossing illegally. The most recent data he shares shows that the Border Patrol had a target of apprehending 81% of illegal crossers in 2021 and beat their target by nearly 2%. It's true that nearly one in five illegal crossers were not apprehended, but that's a far cry from those screaming OPEN BORDERS!

He shows in the thread that there was a time when we had 2 million unlawful entries on the Southern Border. That was in 2005 during the second George W. Bush term.

He also points out that two policies have limited entry: metering at border crossings (which gets people stuck in Mexico) and the ongoing impact of Title 42. The latter was enacted during Covid to control the pandemic. The Biden administration has tried to end that program but both Courts and Conservatives have blocked those efforts.

As we come back to the Venezuelans last week, they fall into a special asylum category. We can’t return them to their home country (also true with Cuba and Nicaragua) because we don’t have diplomatic relationship with the country.

In both of these cases, a careful consideration of the actual data gives us a much more nuanced picture of crime and immigration. With both topics, carefully segmenting the data (as I’ve tried to do) not only minimizes the demagoguery in politics and media. It also helps us see that there are policy solutions that those interested in governing could find once we triage the data.

As Pfaff points out, homicide is excluded in the NCVS because…duh, no victim survey response.

There is no Law and Order: Pub Crawl series.

As Pfaff observes, this increase flies in the face of the common wisdom that post-George Floyd people are unwilling to trust the police.

There is currently an investigation about the situation by a Sheriff in Texas, a lawsuit in Florida filed by a state senator regarding the funding of the stunt, and a lawsuit in Massachusetts filed by some of the asylum seekers. Last night Chris Hayes suggested that the DeSantis stunt had parallels to Chris Christie’s Bridgegate.

If they are asylum eligible, they can present themselves as such upon interdiction.

Thanks again John.

I had no idea that we had over 2 million crossings was during George W's time in the White House. That’s not something the Republican party would trumpet.

I appreciate the wisdom about the nuances of interpreting data--thank you for sharing this data with me and guiding me through some of it. (In an optics lab in my class yesterday a student group had issues related to this... turned out they really didn't understand the procedure in the first place—their data was good, but what they measured wasn’t what the procedure was investigating!)

Your comment early on “Data has a remarkable way of complicating political talking points” is spot on. In our era of 24/7 news, busy people with bills to pay (me!), and short attention spans, simplistic talking points will dominate. We don’t really have an informed population that would watch a talk on data analysis. (I’m not even sure some of our politicians would understand data analysis.) I’m also not sure that a competent, honest, “Mr. Smith” could go to Washington these days.

God bles.