The Big News last week was that Democrat Mary Peltola won the Alaska Special Election to replace the late (and colorful) Representative Don Young.1 She beat Sarah Palin who was well known (for good and for ill) and endorsed by former President Trump (for good or for ill).

But the real story behind Peltola’s victory lies in changes that Alaska has made to their voting procedures. The first big innovation for Alaska was the Jungle Primary.

In a Jungle Primary, all candidates — regardless of party — compete in a single primary election. The field is then winnowed to the top four candidates who receive at last 25% of the vote. These move on to a second vote.

The first round of voting took place on August 16th and included ten candidates. Another twelve had been disqualified or had withdrawn before the 16th. When the voting finished on the 16th, only three candidates — Peltola, Palin, and Begich — moved forward. The fourth place finisher only got about 4% of the vote and was not able to be considered in the next wave.

It’s worth noticing how the pattern (and the campaigning) would be different in a traditional partisan primary. Two candidates — one democrat and one republican — would have emerged for a head to head. The advantage of the jungle primary is that it moves candidate quality above partisan loyalty as voters are making their decisions.

A second electoral innovation in Alaska involved Ranked Choice Voting (RCV). Traditional voting prioritizes the first choice of candidate. Feelings about any of the others become irrelevant.

RCV allows for a more nuanced approach to election of candidates. First, to win election, a candidate must win a majority of votes cast.2 In RCV, voters identify their preferences for each candidate running, listing first, second, third, and fourth preferences (as stated above, there was no fourth candidate in Alaska). If on the first wave, a candidate has 50%-plus-one of votes cast, the election is over. If that doesn’t happen, the lowest finishing candidate is dropped and the voters’ secondary preferences are allocated among the remaining candidates. If the new count puts a candidate over the 50% threshold, the election is over. If not, the new lowest finisher is dropped and the cycle repeats.

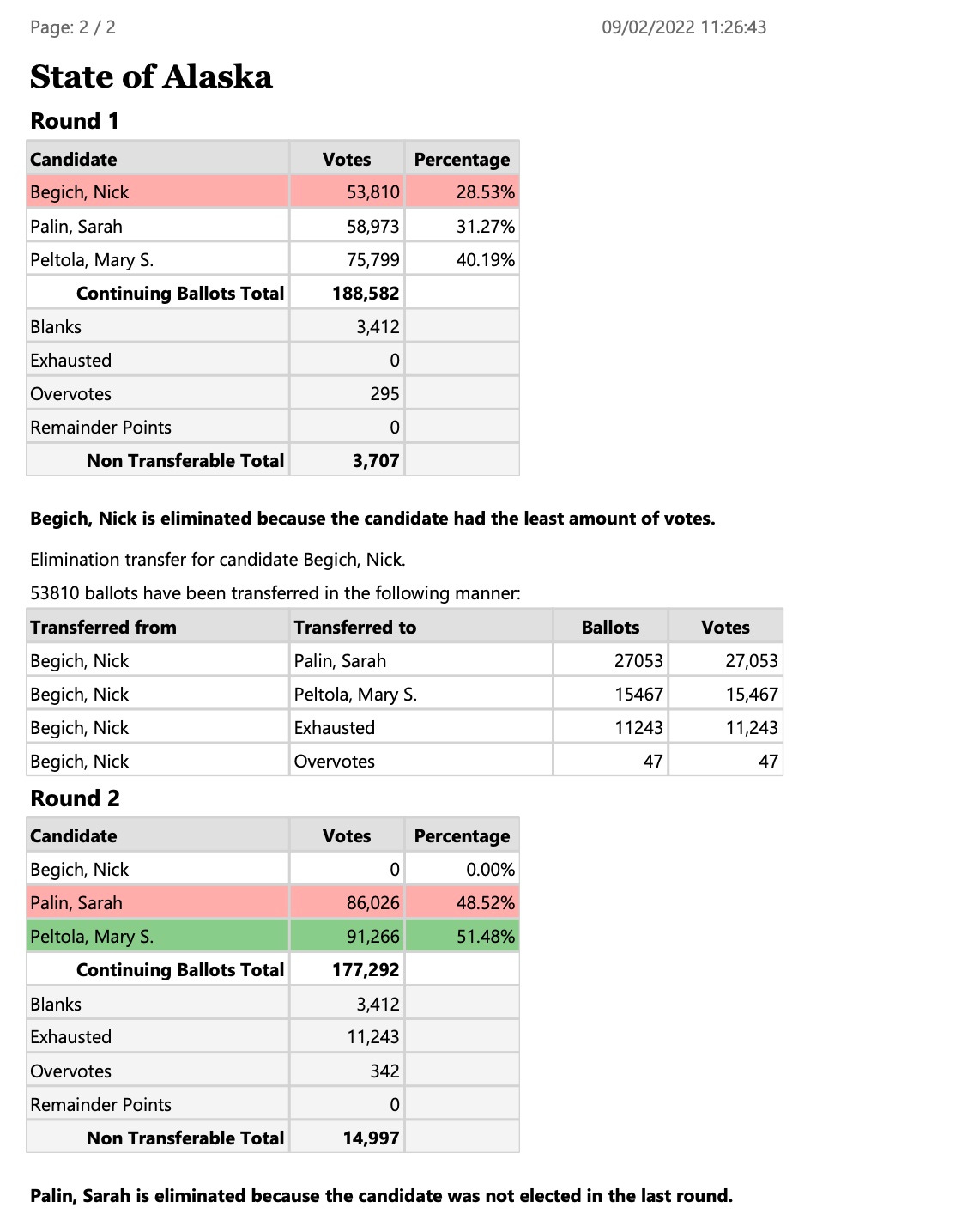

You can see how this played out in the Alaska special election.3 Helpfully, Alaska provide a very clear explanation of how the process worked. Here is what they reported:

In Round One (with candidates listed alphabetically), nobody got to a majority position. Peltola received the largest share of votes at 40%. Palin is second and Begich comes in third. Having two republicans and one democrat in the race changes the dynamics that would occur in a traditional primary (although we can’t assume that all Begich votes would have gone to Palin — more below).4

Following RCV rules, Begich is dropped from contention in Round Two. His votes are then divided among Peltola and Palin according to the second choice listed by voters in Round One. As the middle part of the above chart shows, Begich’s 53,810 votes were divided up among the two remaining candidates: 27,053 to Palin and 15,467 to Peltola. Adding these votes to the Round One totals gives Peltola 91,266 to Palin’s 86,026, putting Peltola over the 50% threshold and giving her the victory.

One particularly striking thing about the race is the 11,243 “exhausted” votes in the Begich first round. What that means is that over 11 thousand Alaska voters opted NOT to select a second place finisher. Those voters who didn’t participate in ranked choice gave Peltola enough of a margin to get a majority. The polling that showed Palin with a 40-60 favorable/unfavorable rating likely made the difference.

RCV is somewhat new in Alaska, so it’s possible that people didn’t understand the rules. Or maybe they did and just didn’t want the pundit and part-time governor to be their one congressperson.

On balance, however, I think both jungle primaries and ranked choice voting are very positive electoral reforms.5 They lessen extreme polarization and expand people’s voice in democracy.

In exploring these electoral reforms, I also discovered that Alaska has had a non-partisan redistricting board since 1998. These boards, which now operate in several states, have great potential to lessen the impact of gerrymandering. At least they would if state legislatures would quit trying to weaken them.6

So Alaska has achieved what I think of as the Trifecta of election reforms: Jungle Primaries, Ranked Choice Voting, and NonPartisan Redistricting. Now all they need to do is join the National Popular Vote Compact7 and they’d be perfect.

Thanks to my former colleague Mark Edwards who suggested that I tackle this topic.

In numerous states this cycle, the “winning” candidate only carried about a third of the total vote even in partisan primaries. That’s how we get candidates like Oz or Vance or Lake.

This was only the election to fill the balance of Representative Young’s term. They get to do this all again in November.

Senator Tom Cotton tweeted that this was a travesty and that Palin was robbed. I told my friend Mark that if Cotton was opposed, there must be great value in this process.

They aren’t necessarily tied together. You can have a plurality based jungle primary that simply moves the top two candidates to the next level (CA system). But you can’t do RCV without a jungle primary.

Another sign that they have the potential to accomplish their advertised ends.

This is an agreement among states that the popular vote totals in each state will automatically be added to the total for each candidate in presidential elections. This eliminates the winner-take-all dynamic that sets the electoral college against the popular vote. It has been enacted by 16 jurisdictions (15 states plus DC) for a total of 195 electoral votes. Once enough jurisdictions adopt to total 270 electoral votes, it becomes law. Alaska’s 3 electoral votes wouldn’t get us there but it’s consistent with their other reforms.