As I’ve written, media portrayals of the criminal justice system have created the moral imagination we use in thinking about Crime, Enforcement, Adjudication, and Punishment. Consider the famous opening to the long-running parent of the Law and Order franchise:

In the criminal justice system, the people are represented by two separate yet equally important groups: The police, who investigate crime, and the district attorneys, who prosecute the offenders. These are their stories. [dun dun].

Technically, it is only the prosecutor who represents “the people” because any offense is considered a “Crime Against the People of the State”. Before the victims’ rights revolution of the 1980s, victims played almost no part after giving initial information to law enforcement.

But this L&O framing ignores the role of the defense attorneys (either hired, appointed, or public defenders, depending on jurisdiction). They represent the accused but in some ways are also representing the people’s interest in constitutional order. The judge is also lacking from the framing and her role is often minimal and procedural in the L&O franchise.

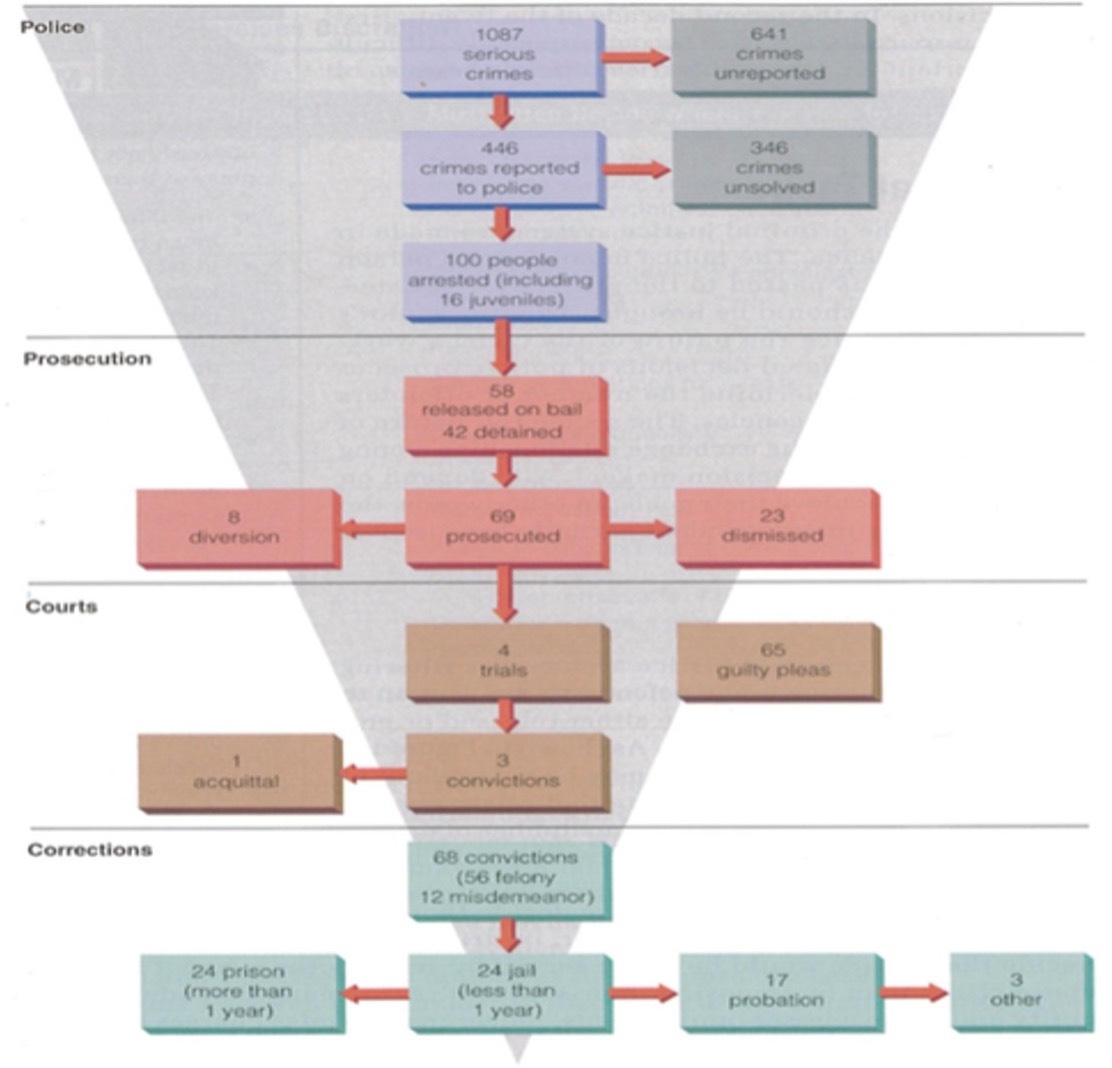

Stepping back to observe the entire process, it becomes clear that things are not as tidy as “ripped from the headlines” stories would suggest. An important early lecture in Introduction to Criminal Justice explained the “criminal justice funnel” which illustrated how a case moves through the system. I paired that with information from a study1 that evaluated outcomes from more than 1000 actual crimes.2 The pairing is illustrated in this PowerPoint slide.

The first point I would make is my class is that each of the four levels separated by the horizontal bars have different decision rules guiding their behavior.3 For the police, the bar to reach is Probable Cause. In other words, does it seem likely that the suspect is responsible for the crime? For the prosecutor, it’s about Preponderance of Evidence. Does the evidence in the case line up in such a way that the case is likely a winnable one? Of course, in court the threshold for the judge and jury becomes Beyond a Reasonable Doubt. For Corrections, they are making decisions on How the Prisoner Has Behaved. While they look back at the severity of the incident, actions on early release (or alternatively, solitary confinement) are the result of rule-following within the correctional setting.

These decision rules (especially before corrections) are important to keep in mind. When someone who is arrested is not prosecuted, that doesn’t mean that the prosecutor “let them off'“. I means that the evidence was insufficient. When the judge rules out “poisoned fruit” evidence, it doesn’t make the judge liberal, it means that he’s following the bill of rights and not “letting someone off on a technicality”. If the jury acquits, it means that there was too much reasonable doubt, not that a criminal “walked free”.

The second point I would make is to explore what happened to those actual crimes and what those numbers tell us about the Criminal Justice System. Picking up on where the last newsletter ended, of the 1087 crimes in the study, less that 500 were actually reported to the police. Of the 446 crimes that were reported, only 100 were solved with an arrest.

As we move into the Prosecution segment, the first decision has to do with whether to release the arrestee on bail. Just under 60% were released on bail and the remainder were held in local jail. I want to pause here because the question of bail has been big in the news lately. There are two reasons why bail would be denied. One is that the offender is a risk of either violence or flight from prosecution. The other is that the arrestee cannot afford the cost of bail. As a result, they remain in jail awaiting trial often for more than a year.

Some jurisdictions, recognizing the inequality of holding alleged offenders in jail even though they’ve not been found guilty, have eliminated cash bail for some offenses. This results in people being able to keep jobs, stay with their families, and remain engaged in the community. This practice has been recently criticized in San Fransisco, New York City, and other locations.4 Rather than deal with a system that purports “innocent until proven guilty” critics prefer to keep “violent criminals” in jail. There is no evidence of a connection between cash bail and increased crime rates, as a number of no-bail advocates have argued.5

Regardless of bail status, of the 100 cases considered by the prosecutor’s office, nearly a third were dismissed without going forward. Another handful were sent through diversion channels. These are often programs for drug, alcohol, or anger recovery. Successful completion results in charges being dropped. That left 69 cases out of the 100 moving forward with prosecution.

Of the 69 cases, only four went to trial (makes for a quick L&O season!). One of those resulted in acquittal and three in conviction. The remaining 65 cases were concluded as a result of guilty pleas. While the study didn’t explore the charge pled, it is often either a lesser crime than originally charged or the reduction in a number of charges moving forward.

As this study suggests, plea bargaining is an integral part of our criminal justice system. In fact, the process would break down without pleas. Sometimes defendants plead guilty because they know they were responsible for the incident. Other times, however, the plea comes as a rational calculation comparing time away from family regardless of guilt. If one can avoid spending a year in jail awaiting trial and instead serve a few months and have it all done, there is an incentive to plead.

This is one of the places where a “tough on crime” prosecutor has control over the situation. Sometimes there is actually abuse as in an infamous case in Tullia, Texas where a crooked cop acted with a prosecutor to obtain 30 guilty pleas from innocent people accused on being in a supposed drug ring.6 Furthermore, a prosecutor’s discretion to charge multiple stacked offenses (combined with mandatory minimum sentences) may be a driver in our mass incarceration explosion according to research by John Pfaff.

The plea bargain is offered on behalf of the prosecutor to the defense attorney, who presents it to the defendant for a quick yes or no decision. Public defenders and other attorneys often have very full slates and have but a short period of time to reach a decision.

In the final season of “The Good Wife”, the lead character Alicia Florrick is no longer at her law firm and is restarting her career in bond court. She is handed a stack of files representing defendants who are attempting to avoid jail. Of course, she takes the most egregious of these and wins some battles. I mention it because it is one of the few times that criminal justice television gave any visibility to a practice that is central to our court system.

At the end of the process in the study, there are 69 people considered for processing in the correctional system. The majority of these go to either jail or prison (depending on length of sentence). Another seventeen are sentenced to probation, which leaves them under correctional care but not incarcerated. If probation terms are violated, an in-cell sentence would result. The last handful are undefined but likely engaged in some type of post-conviction diversion.7

Even though each of the components of the criminal justice system have different decision rules, one thing that guides all of them is a massive power imbalance between criminal justice actors and the individual. It works because the public (influenced by media coverage) believes that the offender, just like Doc Ock, is already guilty and are just waiting for the system to confirm that prior judgment.

Whose reference I have lost — if you know it, put it in the comments

As reported through victimization studies, which differ from Crimes Known to the Police as they result from surveying people to see if they have been a victim in the prior year.

This is another reason why I referred to the Criminal Justice “System” in the opening of this series. The quotes get cumbersome, so just remember that’s what I mean even if the quotes are missing.

This became freshly incendiary in the case of the man who attacked New York gubernatorial candidate Lee Zeldin. The county prosecutor, who served on Zeldin’s campaign committee, charged the offender with an offense that allowed no bail. Zeldin, who had been a critic of bail reform, jumped on the case as an example of criminal justice gone wrong.

There are a number of current and former public defenders and journalists I follow on Twitter who have continued to ring this bell. Here is a short list: Radley Balko, Lara Bazelon, Scott Hechinger, and Alec Karakatsanis. Any of these are worth following for better information on criminal justice.

This should be an outrage. Having innocent people plead guilty to offenses they know they did not commit is a potential feature, not bug, of our current practice.

I wish the study had been able to one more step. I’d love to know the differential recidivism rates (i.e., committing subsequent offenses after release) from the jail, prison, and probation populations. My guess it that is would not show that prison reduces future crime.

I share your outrage at innocent people pleading guilty to avoid jail—or even the risk of jail. As I mentioned in an earlier post, I know someone who did just this, after being coerced and threatened by an officer in the criminal justice system. I see no way this can be fixed.

I believe that Chuck Colson—even after he was released—was not allowed to vote for some 30 years or so, despite the fact he’d properly served his time (and he even started a prison ministry). I’d like to see folks who committed just one crime that involved no violence have their name cleared after peacefully serving their time. Indeed, I believe Colson wanted to shift to a more restorative system of justice… if, say, you stole from someone you were released to serve and, over time, pay back as best as you could.

I appreciate your hard work on these newsletters. Thank you!

Is the note #1 study from Buil-Gil, Moretti, and Langton? I was only able to read the abstract & sample, but it seems to be on the track of your graphic. I couldn't find one (via Google searches; I don't have a handy academic library) that had the exact numbers in your graphic (e.g., starting with 1087 actual crimes and 641 unreported numbers).