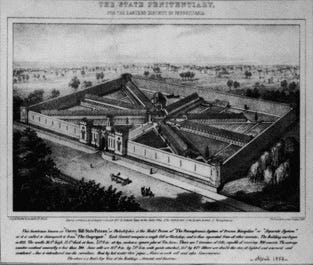

In the summer of 2010, I attended a conference of Christian Sociologists at Eastern University outside Philadelphia. It was hosted by two of my long-time friends on the faculty there. In addition to the conference proceedings, we took a field trip to visit Eastern State Penitentiary.

Eastern State was the first prison actually operating on the idea that prisoners would be penitent. They would reflect on their bad actions, consider where they went wrong, and pray God that they are changed in the future. Opened in 1829, it was nothing if not austere.

Some of that austerity came through immediately as we toured a 181 year old facility. But what has stuck with me over a decade later is the design of the cells.

The cells were spartan to say the least. Each one contained a bed and a writing table. There was a skylight that provided the only natural light available. There was only a small opening in the door through which food would be passed by guards who wore hoods. The whole idea was to completely isolate the inmate.

The oversight of the prison was based upon the idea of Jeremy Bentham’s “panopticon”. A minimum number of guards could observe every cell in the double-decked facility from a viewing point in the middle of the prison.

In spite of the creators’ best intentions, Eastern State didn’t live up to the hopes of individual reform. The severe isolation in the cells and the absence of human contact led to high rates of mental illness and suicide. The hooded guards became much more like today’s correctional officers. A second problem was the the incarcerated population grew beyond the design capabilities of the facility. In the middle of the twentieth century, normal cell blocks were added within the walls and between the spokes of the original facility. No attempt was made for penitence, just incapacitation.

In January of 2019, I took a group of students to visit the Cell Block 7 museum at the Jackson State Prison.1 (The museum closed that November.) During the tour, I could only reflect on what I’d seen in Philadelphia. The cells bore a certain similarity to Eastern State.

Not all prisons are like Eastern State or Jackson. Many prisons allow double-celling, were there are two inmates per cell.2 But the cells still have more in common with the historical models than we’d like to admit. This is even more the case when we consider the practice of solitary confinement.

The New York Times reported last week the death of Albert Woodfox, an inmate at the Louisiana State Prison known as Angola. He had served 42 years in solitary confinement after being accused of killing a correctional officer (which he denied). As the Times describes:

Mr. Woodfox’s punishment defied imagination, not only for its monotony — he was alone 23 hours a day in a six-by-nine-foot cell — but also for its agonies and humiliations. He was gassed and beaten, he wrote in a memoir, “Solitary” (2019), in which he described how he had kept his sanity, and dignity, while locked up alone. He was strip-searched with needless, brutal frequency.

Woodfox’s treatment is reminiscent of the infamous Stanford Prison Experiment.3 As originally reported, Stanford males who volunteered for the experiment were randomly assigned the role of guard or prisoner in a facility Philip Zimbardo had constructed in the basement of the Psychology building.4 The “guards” were given uniforms while the “prisoners” were made to wear dresses and hairnets (because Zimbardo didn’t get permission to shave their heads). Over the course of the experiment, some guards became overly brutal5 and many prisoners became increasingly depressed or agitated.

Sociologist Erving Goffman characterized situations like those faced by Woodfox and the Stanford students as representing “total institutions”. Total institutions were defined by four factors: 1) a totalizing sense of schedule with all of life being defined by the institution, 2) a mortification process through which persons were stripped of individuality; 3) a strict code of behavior that rewards right behavior and severely punishes noncompliant behavior; and 4) a means of adaptation through which inmates develop their own operating systems within the total institution.

This last step is known as “prisonization” as introduced by Donald Clemmer in 1940. It reflects the ways in which culture within the prison is adopted by the individuals within it. One figures out whom to trust, how far to push things, informal economies, and coping mechanisms. Making these changes are necessary for one to successfully navigate the internal dynamics of the prison (and stay out of fights and/or solitary confinement).

Prisonization, to the extent it has been internalized by the inmate (or guard), makes change difficult. Making the adjustments required to learn from one’s mistakes, repent of past behaviors, and prepare for life on the outside is limited by the actual lived environment of those inside. To point out what I think is obvious, it’s exactly the same problem faced by Eastern State inmates in the 19th century.

When the time for parole/release comes around, the inmate has accommodated to the institutional environment. Learning how to behave “outside” becomes a challenge. Here is the end of Albert Woodfox’s Times obituary:

After being released, Mr. Woodfox had to relearn how to walk down stairs, how to walk without leg irons, how to sit without being shackled. But in an interview with The Times right after his release, he spoke of having already freed himself years earlier.

“When I began to understand who I was, I considered myself free,” he said. “No matter how much concrete they use to hold me in a particular place, they couldn’t stop my mind.”

It is encouraging to see many states taking a fresh look at “ban the box” laws, which eliminate the question of prior conviction as a screen for denying employment. Recognizing that there many be extenuating circumstances in an otherwise employee’s background that can be explored at an interview is a positive step. So are halfway houses and community treatment centers (which both struggle with “Not In My Backyard” reactions).

But we need to rethink our reliance on mass incarceration as our chief criminal justice strategy. It removes individuals from community support, puts them in an artificial environment that inhibits their operation on the outside, and is vastly more expensive that available alternatives.6

The “new” Jackson Prison opened in 1926.

In the midst of the overcrowding crisis in California, the gymnasium was turned into a double-bunk dormitory.

As I mentioned before, the Zimbardo experiment has recently been challenged for not disclosing the role that the psychologist played in coaching guard behaviors.

The Stanford experiment is taught in research methods classes as an example of ethical violations.

The later evidence suggests that the guards knew they could be brutal and played it as a game.

Wednesday’s newsletter addresses the lousy return on investment provided by current criminal justice practices.

UPDATE 8/9

This morning I came across “The Visiting Room Project”. It’s a series of interviews conducted with 100 inmates serving life without parole at Angola (where Albert Woodfox was). I’ve only watched a few of the interviews but one wonders how these guys are benefitting from being incarcerated some 20-30 years from their crime.

https://www.visitingroomproject.org/