The Bullwark’s Jonathan V. Last calls this “the Vibes Economy”. Never mind about macroeconomic indicators or the recent history on inflation or the views of the Federal Reserve or the actions of the stock market.

No, the economy can only be measured by dissatisfaction with rising prices of gasoline or eggs or chicken or fruit. According to JVL’s colleague Sarah Longwell’s focus groups, people see those prices go up every day and they don’t like it.1

There are many explanations for these ongoing price increases and most of them aren’t a result of government policy. One exception that’s been argued is that the Covid relief funds provided families with a financial safety net in the midst of a global crisis. As those ended, that cushion went away and the prices became a struggle.

Costs to suppliers went up, which impacted prices. In addition, some companies took advantage of the crisis to raise their prices; evidence for this is that major companies are suddenly lowering prices on their product (but not to the pre-crisis levels). I read this week that one of the byproducts of tariffs on imported goods is that it allows domestic suppliers to raise prices to just below the imported product.

Some of what is presented to the public by social media and legacy media is distorted. You don’t see reports on gas prices in the midwest but almost every story about gas prices has a picture (taken who knows when) of a gas station in California (which requires a special blend that is more expensive). You see isolated claims about skyrocketing prices for certain items (which is often a response to some supply disruption).2 Then there are the stories about that homemaker who has to choose bargain brands because milk is more expensive.

These stories feed the Vibe economy. It’s why people report that their personal finances are in good shape but they’re sure the economy in the country is in the tank.3

All of the above is context for what I want to rant about. I want to focus on the role of polling in creating these Vibes. Sometimes this is a function of not asking the more in-depth questions that would give meaning to responses. I wrote about this when I came back from the Religion News Association convention and Pew’s tendency to ask about “religious beliefs” without digging into how those were expressed.

During my break from this SubStack to work through my copyedited book, I saw a story about a Harris Poll conducted with The Guardian. As the Guardian reported:

55% believe the economy is shrinking, and 56% think the US is experiencing a recession, though the broadest measure of the economy, gross domestic product (GDP), has been growing.

49% believe the S&P 500 stock market index is down for the year, though the index went up about 24% in 2023 and is up more than 12% this year.

49% believe that unemployment is at a 50-year high, though the unemployment rate has been under 4%, a near 50-year low.

To their credit, the story goes into great detail about why these views are wrong. It also underscores the role that partisan polarization feeds this data, with Republicans believing the worst (which will suddenly reverse in January if Trump is reelected).

The Washington Post’s Catherine Rampell had a great opinion piece about the Harris-Guardian poll. She wrote:

But none of this explains why the public appears so wrong about more straightforward metrics, such as whether unemployment is at historic highs or whether the stock market has risen or fallen recently.

Many commentators (particularly those on the left, who are furious about how these misperceptions reflect upon President Biden) blame the media for the public’s economic illiteracy or for leaving the public with the impression that economic conditions are terrible. I agree that we journalists generally give more play to bad economic numbers than good ones. We’ve also done a lousy job of helping the public understand what the right benchmarks are, such as whether they should expect prices to fall outright, what counts as a “good” GDP report, or how our outcomes compare to those in other countries.

But here’s a secret: If the media has a bad-news bias, that’s because our audiences have a bad-news bias, too.

Unfortunately, the Guardian story doesn’t provide a link to the actual questions asked by Harris. I assume (unless somebody can point me to the survey) that they asked yes or no or strongly agree to strongly disagree questions. But why would anyone ask such questions about recession or inflation or unemployment? Are we simply documenting that people are wrong about major economic indicators?

I see nothing wrong with asking about personal finances or whether prices are too high (hint: they’ll always say “yes”). Or whether they favor certain policies to improve their economic lot (this usually involves higher taxes on the wealthy so it doesn’t get much play).

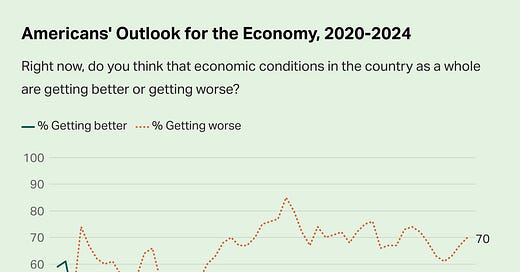

But asking people about factual items as if they were opinion matters seems bizarre to me. Gallup released a report on Friday that, among other things, asked people their view of the economy.

I would have loved for this chart to have a much longer X-axis so that we had better historic context (the right-track/wrong-track data has been upside down for decades). Even still, there are Vibes going on here. Notice that the redline was at 74 in April of 2020 and is now at 70, having peaked at 85 in June 2022.

But in late April 2020, we were six weeks into Covid. The economy had shut down, unemployment was rampant and we didn’t know when things would ever end. Was the economy 11% worse in June of 2022 than it was in the midst of the pandemic? Perhaps asking about that contrast would have been helpful instead of a general question about the economy.

Pollsters could help level-set the conversation before asking the question. If the question had been “are things better today than they were in the midst of the pandemic?” people would have a better referent than their top of head responses. What if the Harris poll has framed their question as “The stock market just hit a record high. Does that give you more confidence about our economic improvement?” One could have done the same thing with questions about recession (“predicted but never happened”), inflation (“near double digits and now under 3%), or unemployment (“longest streak under 4% in decades”).

Of course, such framing wouldn’t eliminate the partisan bias in responses. The out-party will view things in the worst possible light. But at least they wouldn’t make up their own reality.

Here’s one more example of the same polling problem. A CBS poll over the weekend asked respondents if they believed Donald Trump got a fair trial. They report that 56% thought it was fair and 44% thought it was unfair. Naturally, they also reported on the partisan split, with 96% of democrats, 54% of independents, and 4% of republicans saying it was fair.

Now, they had gathered this data by re-interviewing people they had talked to before the verdict was reached. And they found little movement. Of course there wasn’t movement. Not only is the partisan bias heavily entrenched, but they were reporting this data THREE DAYS after the verdict was handed down.

But here’s my point: IT DOESN’T MATTER WHAT RESPONDENTS THINK!

The fairness or unfairness of the trial will be determined by the appeals process as a matter of law and not public opinion. There is no purpose (beyond getting clicks) to ask such a question of random Americans who couldn’t watch the trial (because it wasn’t televised), heard about it only from their information bubbles, and don’t know the law.

Pollsters, our democracy needs you to be better. Please take the necessary steps to make that happen.

End of rant (for now).

But not Costco hot dogs!

Remember Mehmet Oz shopping for “crudite”?

This is parallel to the stories about crime rates and the effectiveness of Congresspeople.