The topics for this newsletter are often prompted by some convergence of unique items that make me look at issues in a new light. One of those clearly happened last week.

My wife, Jeralynne, is reading Sarah McCammon’s The Exvangelicals (now a NYT bestseller!). My reading of an advanced copy has been the subject of two posts on this SubStack. On Wednesday, Jeralynne asked a relatively innocuous question about the 1980s period of evangelicalism and why it developed as it did.

I responded with a lengthy monologue that somehow managed to wend its way from the Second Great Awakening, rural vs urban religion, the modernist fundamentalist controversy and the Scopes trial, the 1940s period of institutional establishment, Billy Graham, Jimmy Carter, The Year of the Evangelicals, the Moral Majority, Christian Nationalism, and Donald Trump.

After 49 years, you’d think she’d know the risk of asking questions like this!

The next day, Katelyn Beaty’s SubStack was titled What “Post-Evangelical” Means to Me. Katelyn picked up some of the same reflections shared by Sarah and Jeralynne. This passage stuck out:

I used to think that evangelicalism — specifically its ’90s and early 2000s Midwestern permutations, with its passionate preaching, purity rings, and puppet ministries — was the entire river of Christian faith. Later, in college and in my first professional and adult church experiences, I learned that in fact, it was actually just one tributary, or more like a trickle sourced from one tributary. And that tributary was one of countless tributaries that all pool water from this great, rushing river we call Christianity.

If you spend your whole life splashing around in the trickle, you might end up with a shallow and stagnant faith. And no wonder so many people leave the trickle entirely, especially if it’s contaminated with narcissistic leaders and consumerism and political idolatry. If you think the trickle is the whole river, then you might leave not realizing there are waters that are deep and mysterious and sustain life — indeed, with the living presence of the Source.

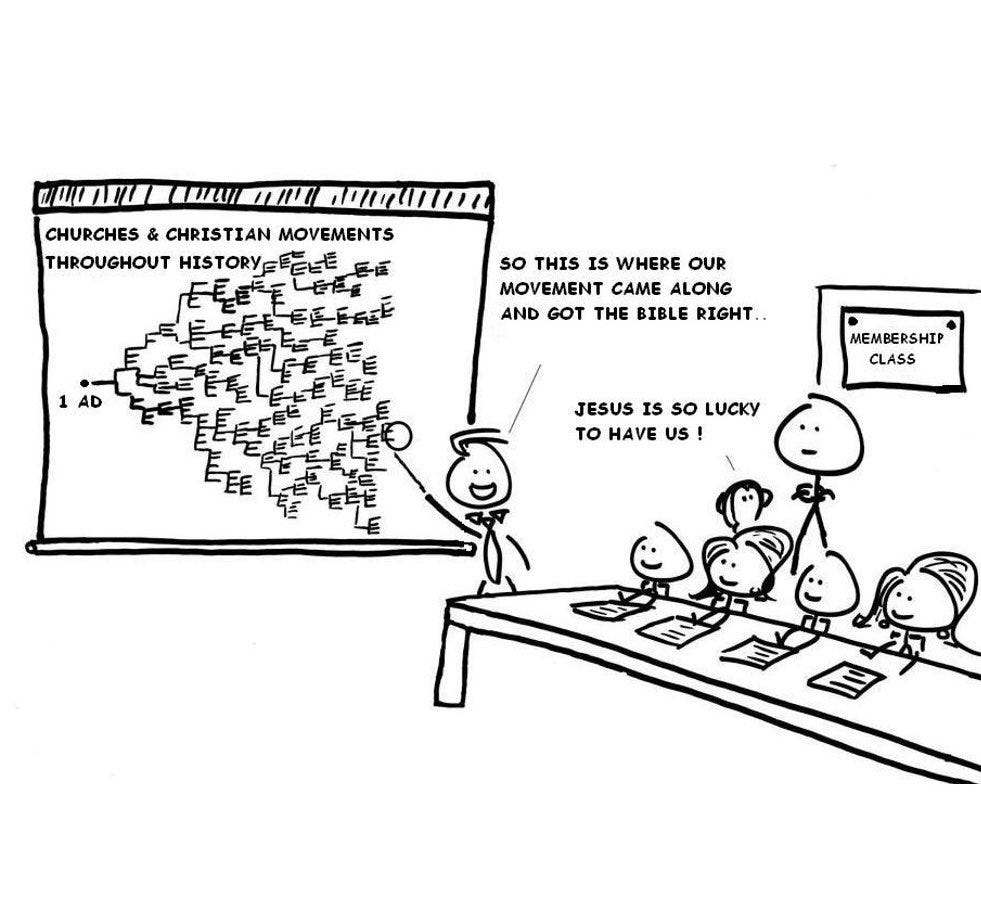

Katelyn’s image of the narrow tributary among countless others, reminded me of one of my favorite church history cartoons. No doubt you’ve run across it.

As a sociologist of religion, I’m normally drawn to data on questions of evangelical identity. I’m a faithful reader of Ryan Burge’s Graphs About Religion SubStack.1 I eagerly open whatever new update I get from the Public Religion Research Institute.2

The Grand Themes I addressed in my response to Jeralynne’s question are rightly the kinds of things historians explore in detail. Each one is full of complexity and nuance that requires attention to detailed original sources. So, with apologies in advance to my historian friends, I’m not doing that. Instead, I’ll examine some broad sociological themes running over those periods of time.3

The Second Great Awakening helped feed the growth of the American Frontier. As towns were established, they needed churches but were often short of clergy, relying instead on circuit riders. This allowed the development of a folk religion Christianity that remains with us (and is a large part of the rural “real American” notion I wrote about recently). It’s also connected to the Doctrine of Discovery that Robbie Jones wrote about in his most recent book.

The rural-urban split is a key part of late nineteenth and early twentieth century life. The cities were seen as places of evil.4 Moreover, the urban clergy were not only seminary trained, but were learning about Historical Criticism and science. The modernist-fundamentalist controversy followed. More correctly, the conflict was one-sided, with the fundamentalists critiquing the modernists. The Scopes trial is one of the latter stages of the conflict. The fundamentalists won the battle and lost the war.

Twenty years later, some conservative groups distanced themselves from the stridency of the fundamentalists. The National Association of Evangelicals5, Christianity Today, and a number of other organizations developed in this period.6 Billy Graham crusades coincide with the advent of television to popularize the evangelical approach.

The 1960s and early 1970s brought what sociologist Jeffrey Hadden called The Gathering Storm in the Churches. As urban mainline clergy were supporting civil rights causes and critiquing the Vietnam War, they found themselves increasingly at odds with their congregations. Evangelicals pointed to those stances as yet another example of mainlines losing their way. Dean Kelley’s Why Conservative Churches are Growing provided more justification for why evangelicals were right.

Jimmy Carter gets elected president in 1976, being the first candidate to public declare he was “born again”. In short order, evangelicals were seen as a movement. Both Newsweek and Time declared a “year of the evangelical” (one in 1978 and one in 1979). But Carter didn’t fit the NAE/Billy Graham mold. He was left of center. Most significantly, his administration denied the tax exemption of Bob Jones over their racial policies. Suddenly, he was anti-religion. Randall Balmer’s biography of Carter illustrates how the evangelicals moved away.

Another wave of evangelicals institutionalization follows in the 1980s. The Moral Majority, the Christian Coalition, and Focus on the Family are born. Their focus was not on theology per se but on politics and social issues. Real Christians were to be different from social Christians who were concerned about accommodating culture.

The period Katelyn describes follows. Having separate cultural markers on issues like sex, music, dress, prom create a unique subculture.7 Unique cultural artifacts follow: Purity Balls, See You at the Pole, Teen Mania and the like.8

For a variety of reasons, these alternative structures were hard to sustain. The harms of purity culture became readily evident. As young adults engaged a broader world through social media, the parochialism of their teen years just didn’t make sense. Add to that concern over LGBTQ+ friends, and the structures seemed way too rigid.9

Which gets us to Trump and Christian Nationalism. Tim Alberta’s recent book explores the mentality that undergirds this thinking, even as he struggles to reconcile it with his understanding of the Christian Faith.

So what do I take away from my 35,000 foot look at evangelicalism? First, what we think of as evangelicalism has operated as what I would call “a negative referent”. In other words, evangelicals were not crazy fundamentalists but they also weren’t urban mainliners. One positioned oneself as Not The Other Guy.

It’s also important that the negative view of the other is often a caricature. Those people attending mainline churches weren’t really folks who didn’t believe anything (or believed everything) but the evangelicals had their own systems and networks where they talked to each other. The suburbanization of the evangelical church furthered that separation.

The ways in which evangelicals redefined everything as “deeply held religious belief” also contributes to the isolation. It’s not that they differ on policy issues like small government or immigration policy. It’s that the conservative position gets sanctified as a religious position. Significantly, this is in contrast to articulating actual religious beliefs related to theological tenets or scriptural themes.

Finally (for now) creating separate cultural systems in music, purity culture, youth group, and the like are increasingly difficult to maintain in contemporary society. This is a primary reason why I wrote my book. Simply having Christian universities continue to operate as subcultural identity supports will not work with the current generation of students.

I don’t know if all this adds anything to the broader conversation about evangelicals in the 21st century. But it helps me to try to think of broad trends.

I’ll now defer to my history and theology friends to point out all the important nuance and detail that I glossed over.

I’m grateful to Ryan for recommending my SubStack to his followers, which has significantly increased my subscription list!

Their new report on Religious Change will be the focus of Wednesday’s newsletter.

I’m reminded of a discussion group I attended at the Institute for the Study of American Evangelicals forty years ago. I was the only non-historian in the room (and some great ones were there). The discussion had turned to whether 1980s evangelicals could appropriately trace their roots to Princeton in the early 20th century. My response was that we needed to address whatever those evangelicals thought they were.

I once had a copy of an early 20th century ad for Asbury describing it as being “75 miles from the nearest known sin”!

The Bebbington Quadrilateral is often cited as key to understanding evangelicals, but that doesn’t show up until the late 1980s.

Richard Quebedeaux labeled them “polite fundamentalists”, a characterization I’ve always liked. Although politeness has fallen from favor lately.

My book makes much of the contrast between Christian Smith’s Subcultural Identity approach to evangelicals and James Davison Hunter’s Cognitive Bargaining approach. Hint: the latter wins.

It was Addie Zierman’s When We Were on Fire that first got me thinking about this.

The new PRRI report demonstrates the ways in which this has influenced religious switching.

This sentence is interesting: “ Simply having Christian universities continue to operate as subcultural identity supports will not work with the current generation of students.”

40 years ago I wrote an article in our denominational magazine, the Covenant Companion, arguing that North Park University (then college) needed to think of its mission as serving the church. Today I think it is more accurate to see it as a ministry of the church to students. I think that is more in line with your comment.

Great read!