It is tempting to write on the long-term impacts of the Supreme Court decisions over the last two days: ending affirmative action, siding with Missouri on the student loan policy, and affirming Creative 303’s desire to not do web pages for same-sex weddings (that no one had asked for). I’ll likely address some of all of those next week when I’ve had some time to reflect. Instead I want to tackle a huge divide in our society that is evident in politics, in health care, in economics and is the major cleavage point in society.

I’ve written before that one of my favorite podcasts is Chris Hayes’ “Why Is This Happening?”. With a minimum of the random chit-chat that haunts many podcasts, he digs in for an hour on major policy issues with researchers in the field. Last week’s episode was a discussion with economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton as they reflected on their 2020 book Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism.

Their research analysis drew heavily on Emile Durkheim’s study of suicide and Robert Putnam’s work on declining social capital, so naturally I was hooked. As soon as the episode ended, I put in a hold at my local library. I’m halfway through but the argument is persuasive enough that I want to write on it now.

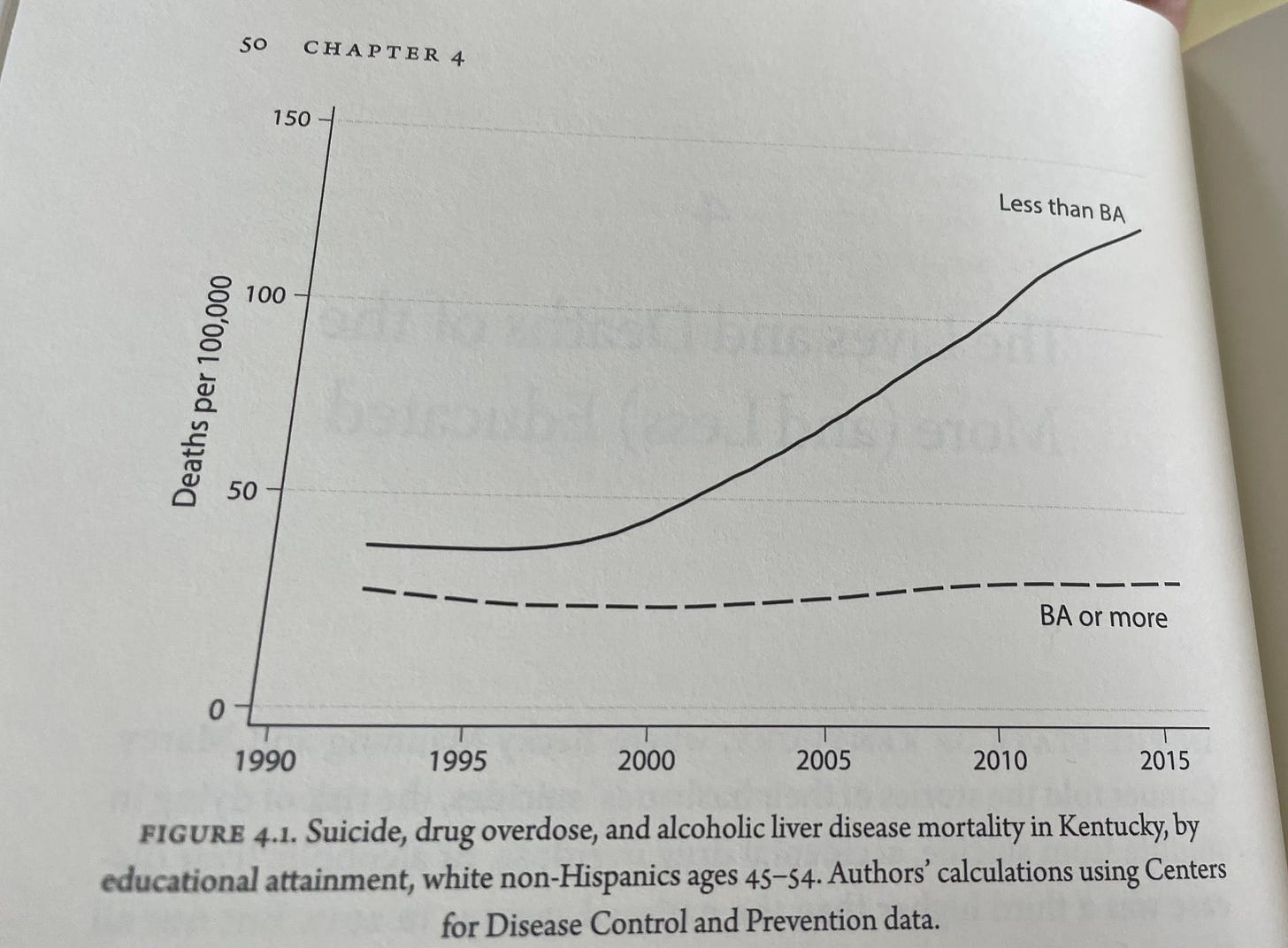

In their work on economic changes over the last 50 years, they discovered a troubling pattern. What they call deaths of despair — suicide, alcohol abuse, and drug abuse — have increased dramatically. But that increase hasn’t been uniform. It is concentrated among those without a bachelor’s degree.1 This chart shows increases in deaths by suicide and alcoholic liver disease for whites who are mid-career in Kentucky.

Where the gap between those with a BA and those without was (rough estimation from Y-axis) around 10 deaths per 100,000 in the early 1990s, by 2015 it had jumped more than tenfold. The with-BA line remains stable while the without skyrockets beginning in 2000.

A host of other charts document similar trends on a national level. When they looked at cohort data (people born in similar points in time) two trends emerge. First, each successive generation of non-BA whites is a little worse off than the one before it. Second, the gap between non-BA and BA continues to increase.

The Durkheim and Putnam stuff enters as the non-BA group has faced a different level of social upheaval including but not limited to economics. Further, the more rural states have lower density feeding less interaction and social support. Unions are weaker as are churches and fraternal organizations.

Not surprisingly, this gap shows up prominently in our politics as the separation between those with college degrees and those without maps directly upon partisan identity, especially among white males. It shows up in the Josh Hawley/Jordan Peterson/Tucker Carlson “what about the men?” fad. It shows up in opposition to affirmative action and student loan forgiveness.

Curiously, it seems like the despair of the non-BA crowd also feeds the “college isn’t worth it” claims. As the non-BA population rightly feels ignored, it’s easier for them to believe the bogus claims that all colleges are indoctrination factories insistent on turning everybody Woke.

Some of this is due to the tendency of the college-educated crowd to talk down to the non-BA group. Characterizing them as racist or backward or ignorant of their economic interests has negative consequences. And, of course, there is a dedicated right-wing media ecosystem that will take every comment out of context, exaggerate it, and demand outrage in response.

The root of the despair that Case and Deaton are describing rests in changes in the American Economy over the period. We don’t like talking about Political Economy because it flies in the face of individual striving and belief in meritocracy.2

The reality is that we have systematically left behind large groups of Americans as the economy changed.3 Those of us in higher education benefitted for a while as the percentage of high school students attending college increased. Now the demographic cliff combines with some ceiling effects to make that difficult.

We celebrated First Generation College students and talked about why they needed special supports (which we cut back as budgets got tight). But we didn’t do enough to see those students graduate. Someone who doesn’t finish isn’t any different than those who never went.

I congratulate leaders like PA governor Shapiro, who has reduced the number of state jobs that require a BA. And recent actions by the Biden Administration — from CHIPS to Infrastructure to IRA — look to make a difference in revitalizing construction and manufacturing. We learned in COVID that people could work away from big cities, which addresses those left behind when the jobs left.

Those of us in higher education benefitted greatly from the economic shifts of the last 50 years. We encouraged people to see the value of a college degree, even given the high impact of college loans. I’m one of those that argued that job prospects for those with only a high school diploma had severely diminished from what was true for the first half of the Boomer generation.

But reading Case and Deaton’s excellent book reminds me that I’ve been complicit in what’s gone on. Why did the gain in a knowledge class require the abandonment of the manufacturing class? Couldn’t we have sustained both of these elements of our economy rather than pitting them off against each other?

I had an email exchange this week with a sociologist who is studying gown-town relationships. It strikes me that those relationships often depend upon the town recognizing the value-added component of having a college in its midst. Perhaps we on the gown side needed to have spent much more time learning about the factories and shops and tool and die operations in the town.

Interestingly, “some college” doesn’t provide that much protection. There seems to be a sharp break between those with a BA and those without.

Looking at you, six SCOTUS justices!

This is the second half of the Case-Deaton book. I’m very much looking forward to it.

Hmm - this has a striking parallel to Jessica Rose's op Ed on the decline in Church attendance which seems to be more common in individuals without a BA:

"every demographic group in the United States is becoming less religious, but groups that are overrepresented among people with no religion in particular are those without high school diplomas, who are single, who don’t have children and who earn less than $50,000 a year."

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/28/opinion/religion-affiliation-community.html?unlocked_article_code=9dIbgh1c8f29v5sZ2wjw6iT1qtiGA3Y75Owix7rJdHDPHcENKxFE9f0-_Zq56Ukv0k3-LNb62MGhX-ct8ZObltHcnWNTM4hD_SYqIia3C1YVUzscauLathsRhgeWaCfqVATUO6_0FmdB7zgqgBfeqEBvSB_co0GNlDQNMqTr0mVc-rchoCPyGE6G3SI_tc6uH0-9JB8MbNc4joTZYplE8nBi2xkU3H_UYwDuqf9rtW940z0DyH3y2FtQeGDSty1BJrCmTxEqh6eEoGzBmeKO6sGTFnUbJypShTTHhznWUHBgoK525p2B4dja-NILZ_ON81_ZmCk3OZTvEnGuoYHIl_6k6lGH7M9w&smid=url-share

It seems both the academy and the church are failing the poor and the oppressed 😭

There is a terrifying divide between "vocational" and "academic" with each side seemingly unwilling or unable to address the division. I proposed a joint program where students would complete programs in carpentry, electric, plumbing, etc. in tandem with a liberal arts degree. Maybe they would get jobs as managers in the manufacturing or service world, or maybe they would like having well-paid hands-on jobs or get inspired and head into grad school or whatever. More options! Appreciation for different ways of working! The admin (at my college) was not interested, vocational contacts were not interested, and in talking to students (a growing number of first generation) - they were not at all interested.