How Christian Universities See Themselves

Peer Institutional Networks Vary

When I was teaching at Olivet Nazarene in the late 1980s, a number of us faculty were encouraging the administration that, due to a variety of recent changes within the university,1 it was time to raise our sights and strive to become more of a regional player in Christian higher education. The administration responded that they’d continue to be happy being “the best of the Nazarene schools”.2 I’ve always felt that this was a lost moment and the beginning of a number of conflicts between faculty and administration over the next few years.

That conversation has never left me. It informs many themes of my book. Is the “Christian” in Christian University the primary characteristic of the university or does it modify the kind of educational experience present? Is the institution “parochial” or “cosmopolitan”?

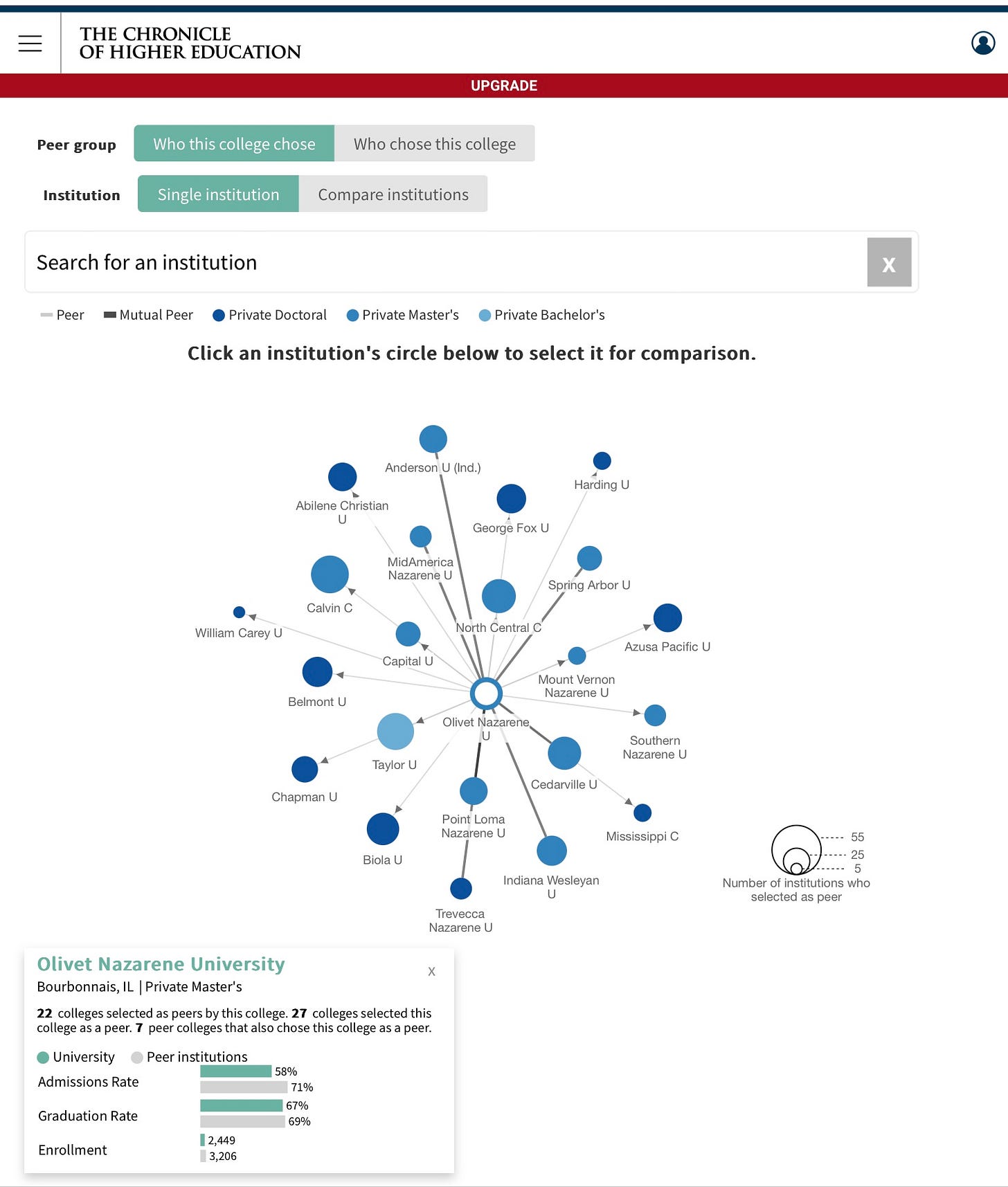

A story that appeared in The Chronicle of Higher Education last week piqued my interest.3 Titled “Who Does Your College Think Its Peers Are?". It provides results the peer institutions schools name as part of the annual IPEDS4 data. The Chronicle reported on 1500 institutions, identifying who they named as peers and who named them as peers.

I took at look at twenty Christian universities, many of which found their way into the data crunching I did while writing the book. There are some methodological limitations, the primary one being that the IPEDS data is highly dependent on who filled out the survey. Nevertheless, the variability is interesting.

The median institution from my list selected 22 peers with a range running from 9 to 40. The median for being selected was 30 with a range of 17 to 42.

Here is the Olivet Nazarene University peer selection.

When I was in grad school I took a class in social network analysis (which was cutting edge in 1980). It allows one to examine a network and determine where meaningful linkages exist. I wrote the author of the Chronicle piece, Jacqueline Elias, to see if the images reflect social network logic. I thought that perhaps (using the Olivet example that Olivet was more similar to Cedarville than it was to Azusa Pacific because the arrows are shorter. She wrote me back and said, no, that just how the graphics package arranged things. I was disappointed (and somebody should do that actual analysis as a masters project!) but was still able to dig more deeply into the data.

I was particularly interested in how likely Christian universities were to select and be selected by other Christian institutions. I made some arbitrary decisions about which schools would be considered “Christian”. So, for example, I left out Lutheran schools, Catholic schools, and Methodist schools. I included some institutions that could be considered conservative Christian even if not officially part of the CCCU.

Of the twenty schools I examined, eight identified Christian institutions as forming over 85% of their peer network. For three of those, 100% of the network were other Christian schools.5 On the other hand, five schools had less than 30% of their peer network as other Christian schools with two having none at all. This doesn’t necessarily mean that those schools are less Christian but it does mean that they see themselves as part of the larger higher ed market. Perhaps this is due to the balance of Christian vs. secular institutions in their region. I find it interesting that the three institutions least likely to have Christian schools in their peer network (Whitworth, Eastern, and Belmont) were the ones who recently changed their HR policies to allow hiring LGBTQ+ faculty or staff.

The three 100% schools were Cedarville, Taylor, and Union. If we look at the connections between the first two, we get this image.

With just two institutions, we have a closed network comprising about a quarter of all colleges in the CCCU. The Chronicle page would only let me pick two schools at a time. I think it would have been great to build the entire CCCU network from a total of 4-6 schools.

My analysis of the second category, who selected this school as a peer, showed a much higher concentration of other Christian institutions picking these schools. Only three institutions fell below 60% in terms of who identified them as peers (the same three as in the first analysis). The most homogeneous schools had networks that were 80% Christian schools (Cedarville, Abilene Christian, and Taylor).

I don’t want to make too much of this analysis. It’s only one piece of data with the limitations stated above. Yet, I think the data is suggestive of something. When it comes to understanding institutional identity, some universities see themselves as Christian first and foremost. Others, while not taking anything away from their Christian commitments, see themselves as part of a larger educational environment.

I think it would provide for some fascinating conversations at the beginning of the next academic year if faculty, administrators, and trustees spent time in conversation about who they saw as peer institutions. It would be very productive to discuss the heuristics available in selecting like or aspirant institutions. It might just set the institution on a new trajectory, unlike what I experienced nearly 40 years ago.

Including the name change from College to University.

A claim that was disputed at the time.

It actually appeared on May 16th and reprinted on the 30th.

Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System

Olivet Nazarene was next at 91% because they identified two area institutions in their peer group.

That's a fascinating tool that the Chronicle put together. One thing I've noticed in 8 years at my CCCU school -- which has undergone some serious turmoil and culture wars recently (and may not recover) which has forced some internal arguments about what it is to be a Christian university -- is that leaders will invoke who are our peers in different ways to suit their purpose. E.g., when it comes to why we pay our faculty so little compared to other local universities (whose faculty also have to live in the same expensive region), or when someone notes that our most common cross-applications are with the local public R1 university, they will disregard those as our peers ("we're not really in the same league") and focus on our Christian identity and play up our CCCU connections, as if really, they form our peers. But when it comes to discounting tuition to "stay competitive," or our broader academic reputation (e.g. in the US News 'national universities' category), or the proliferation of our 'professional' programs offered, or in constantly using consultants to hire the next VP and (of course) set their administrators' compensation to remain competitive, suddenly it's about the larger landscape of higher ed and what non-Christian schools are doing, and our Christian identity or CCCU peers are not relevant. When they have to wring their hands about how enrollments are falling, they'll cite national trends about higher ed, or our region's declining high school graduation rate; but if we get some honor or a faculty member gets a big grant they might be quick to highlight that we were the only CCCU school to get it. And when it comes to seeking more donors, we might point out how well other private colleges nearby are doing with building nice new buildings etc.; but no, the donors we court are mostly just the deeply connected CCCU evangelical types (of which there are, of course, so few, particularly since most of those give to the Wheatons and Biolas and Liberties and Hillsdales of the world).

What was the basis of leaving out the three denominations you ignored?