As I’ve mentioned several times on here, five years ago I was immersed in a project (now abandoned) on millennial evangelical memoirs. The books I was analyzing told a story of people growing up in an evangelical subculture and subsequently critiquing it while searching for other, better, expressions of faith.

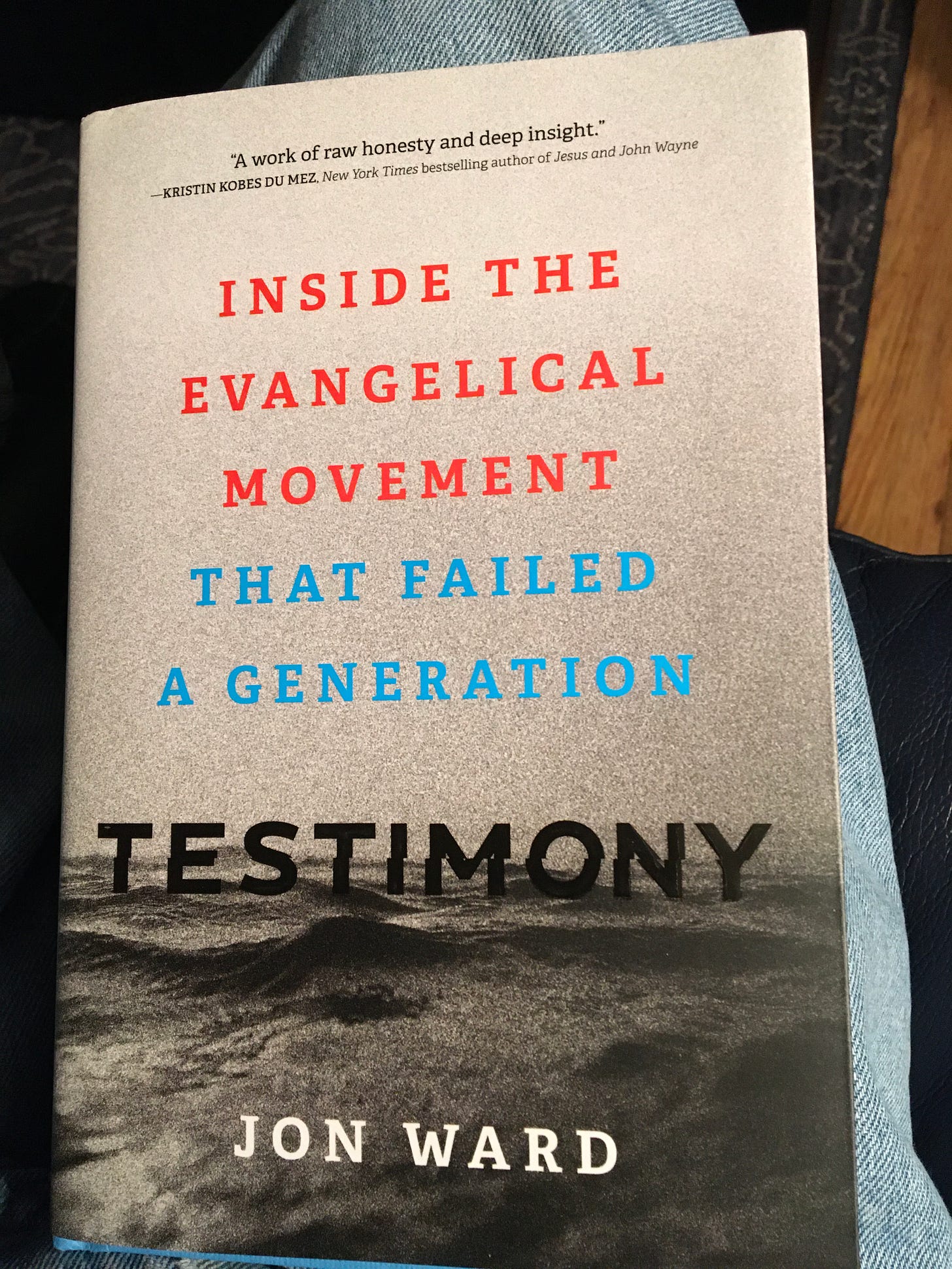

Even though that project didn’t come to fruition, I’m still interested in the topic. So when Jon Ward’s Testimony: Inside the Evangelical Movement That Failed A Generation came out last week, I knew I needed to read it.

Ward1 tells his story in three parts, which he labels “Growing Up Evangelical 1977-2000”, “Separation 2001-2012”, and “Reformation 2013-2022”. The first part describes his life growing up in a charismatic church in Maryland.

[Early on, he mentions that the pastor was his father’s high school friend, C.J. Mahoney.2 That named seemed familiar to me as a scholar of evangelicalism. Then the church became part of Sovereign Grace Ministries and I remembered that it was in the news over not responding to child abuse and called out by Rachel Denholander. It was also home to where Josh Harris (of “I Kissed Dating Goodbye” fame) was pastor before leaving and deconstructing on Instagram.]

That church operated like what Erving Goffman called a Total Institution, where all aspects of life are circumscribed and controlled. Here’s how Ward describes the subculture:

For church leaders, the idea of surrendering to God is a velvet hammer sitting right there out in the open, for easy use anytime. You don't like my decision? Well, you need to submit to God's will. It was never said that bluntly, of course. We developed elaborate rituals and a pseudospiritual language all our own that could be used to corner and subdue anyone who questioned the accepted beliefs. And it was no doubt easy for the leaders who oversaw my Christian training in school, at church, at home to confuse the notion of submission to God with the idea of intellectual surrender. They didn't have much incentive to separate the two.

Here's a typical Friday night youth group meeting. After the songs had been sung and the sermon had been preached and the eyes were closed (by most) and the mood was soft, the pastor would come up on stage and lay it on thick. "How many of you are still holding something back from God? He wants all of you!" The problem is, he would say this to thirteen-year-olds who had no clue who they were yet. So to say, "I give all of myself to God" can easily morph into "I give all of myself to whatever the leaders tell me to do." Talk of surrender is more credible, and a lot more respectful of each child's humanity, if leaders are also giving young people critical thinking skills. Why not teach them Bible basics and the creeds while giving the child space to think for themselves, without emotional manipulation? Well, I can think of a reason. It's harder to control kids that way. (p. 54)

In his teen years, Ward went on a Teen Mania mission trip to Chile playing a clown in evangelistic dramas.3 He also spent summers attending national evangelical teen conferences.

From that moment, I was radicalized. I was "on fire." I had a clarity about my purpose in life, and I took extreme measures to pursue it. I stopped hanging out with my best friend, Steve, because he drank alcohol and didn't listen to Christian music all the time and didn't read the Bible every day. I became a fanatic.

Part of this fanaticism was trying to match the fervor of those meetings in Pennsylvania. Sustaining the emotional intensity became a marker for whether I was excelling at being a Christian or not. And excelling was important to me. I was competitive, driven, ambitious. Our family mythology encouraged this. But at this point in my life, I'd nearly exhausted the sports route. I'd done pretty well in my two years of playing junior college baseball and thought I might try to walk on at Maryland the coming fall. But it was a long shot. So I poured all my energy into spiritual achievement.

For years I interpreted the events of 1997 through the well-worn grooves of storytelling that are passed down from churchgoing generation to generation. I understood my story as simply miraculous. Now I cannot help but notice the ways in which even before I went to the Celebration conference, the net was closing in around me, pulled by human beings who were being paid tc make sure my peers and I got more involved in the church. And I was an easy catch. Pulling me further into the only community I’d ever known wasn't that hard.

I believe miracles can and sometimes do happen. But sometimes we are simply acted on by other people and the worlds they've created, and we call it a miracle. Being open to both is balance faith and reason. It's not something I was taught growing up. (p. 63)

That idea of being open resonated with me and drew parallels to John Seel’s The New Copernicans. Seel argues that millenials (even late Gen X folks) are approaching the world differently that their older peers. They’ve had to in order to make sense of the world around them.

The second part of Ward’s book is the story of his professional career. Shortly after graduating from Maryland, he lands a job as a metro reporter for the Washington Times (founded by the Unification Church’s Sung Myung Moon).4 In 2004, he went through Chuck Colson's Centurion Course, which I'd consider a Worldview course for professionals.5 In 2009, Ward went to work for Tucker Carlson's "Daily Caller". After two years there, he went to work for a short-lived Rupert Murdoch publication called "The Daily".6 Two weeks later he was approached by the "Huffington Post".7 Eventually Ward lands at his current assignment with "Yahoo! News".

I find it very interesting that Ward makes a closed-to-open move in his professional life similar to what he did in his religious life. Several things prompted this shift that he outlines in the last section of the book: living in his neighborhood in Washington D.C., researching a book on the Kennedy/Clinton primary fight in 1980, and seeing the extremism of the Republican party in the Tea Party era and beyond, including the prophetic movement’s embrace of Trump.

His more “open” stance was not without its price. Those family members still living in the closed environment couldn’t deal with his questions and opinions. The text messages he shares are simply painful to read. One hopes that better family relationships can form in the future, but if the last six years have taught us anything it’s not to hold out a lot of hope for change.

But change does occur in Ward’s life. I was encouraged by his comments at the end of the book:

My own faith was dimmed because for years I was told or shown that following Jesus meant avoiding people who don't think like you, prioritizing emotion over critical thought and question asking, and trying to avoid difficulties in life through prayer and other "spiritual" tools. The difference between Christians and non-Christians was supposedly that we were a little weird and should be glad to be thought of that way, because we were old-fashioned on things like sex and drugs and drinking and cussing. But if we just held on, and stayed "pure," we'd get to heaven.

But the faith I was taught beckoned to something I still want: a fullness of life. I am puzzled and discouraged and heartbroken that something that promised so much good has contributed to so much destruction, damage, and hurt. My tribe has sought to escape reality through religion that deemphasizes this world, or by trying to control it and bend it to their wishes. This is not the way of sacrificial love, truthfulness, and weakness. (p. 236)

I’ve always told students that if I hadn’t picked a career that let me study evangelical subculture, I would have gone into politics or journalism. Jon Ward’s book allowed me to look at the intersection of all three areas. I highly recommend it.

Jon Ward was born in 1977, so he isn’t technically a millennial but I’d argue that he was an early innovator.

Mahoney and Ward’s father were both part of the Jesus Movement and their trajectory tracks along with that in Sara Billups’ Orphaned Believers.

One of the books in my earlier project was Addie Zierman’s When We Were on Fire. She also was part of Teen Mania playing a mime for Jesus in the Dominican Republic.

It’s not quite as conservative (reactionary) as Epoch Times funded by the Falon Gong.

Not to be confused the the New York Times podcast!

He doesn’t say this, but I like to think he was hired as a “conservative whisperer”.

C. J. Mahaney is one of those figures that seems to be close to so many different stories within evangelicalism. You mentioned Rachael Denholer and Joshua Harris. But he was one of the original group that founded The Gospel Coalition and Together for the Gospel (T4G).

Tullian Tchividjian was asked to leave TGC blog and at the time it appeared that at least part of his relational break with TGC was because he was critiquing TGC's defense of CJ Mahaney because of Mahaney's defense of sexual abuse within his church network and the authoritarian response to the news of that. (Tchividjian not long after had his own sexual abuse and other misbehavior crisis that led to him being removed from his pastorate and also had a group that came around and defended him.)

Kevin DeYoung was mentored by Mahaney. Mahaney offered to mentor Mark Driscoll and appears to have been close around 2007 when Driscoll was facing an early crisis. Doug Wilson and John Piper both invited to preach or speak at conferences long after issues with Mahaney were clear.

Many of these memoirs seem to have come out of particularly problematic church backgrounds. And I do wonder about how that reality matters.