I have been closely following the research on Christian Nationalism for five years, ever since Andrew Whitehead and Sam Perry’s Taking America Back for God released. The argument is that there is a group of Americans who are looking for Christianity to have a directive role in our society. This extends to beliefs that our laws should be Biblically based and that being a True American requires one to be Christian.

Their work has been replicated by PRRI in a national survey (with a slightly different scale). Matthew Taylor explored the New Apostolic Reformation version of Christian Nationalism. Amanda Tyler wrote a helpful book on how to push back against Christian Nationalism.

The consistent argument in my posts on the topic is that the solution to Christian Nationalism rests on what Whitehead and Perry called “Accommodators”; people who loosely hold favorable views on Christian Nationalism but might be persuaded to distance themselves from the more stringent believers (“Ambassadors”).

Critics of the Christian Nationalism research argue that we are demonizing good Christian patriots who believe in generalized providence and love their country. I recently had the opportunity to participate in an American Values Coalition discussion with Richard Mouw about his book How To Be A Patriotic Christian. I thought the book and the discussion made some useful and important distinctions.

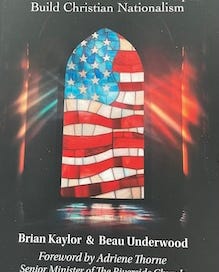

As I have tried to make sense of the Accommodators’ weak view of Christian Nationalism, I finally read Baptizing America: How Mainline Protestants Helped Build Christian Nationalism by Brian Kaylor and Beau Underwood. As a Methodist, it made me uncomfortable.

Kaylor and Underwood trace the history of America’s “God and Country” efforts going back to the late 19th century. Since the modern evangelical movement was still 50 years away, it’s not surprising that efforts to declare the US a Christian nation were generally mainline efforts.

It was mainline leaders who, in the midst of Cold War fears, prompted the government to add “Under God” to the pledge of allegiance, to put “In God We Trust” on our money, and to create a Presidential Prayer breakfast. It was mainline politicians who regularly invoke God in political speeches. It is telling that these efforts had less to do with religion per se than to draw contrasts to Atheistic Communism.

One of the chapters caught me up short. It explored Robert Bellah’s famous1967 essay on Civil Religion. Bellah argued that America has a civil religion that is not quite Christian, believing in a vague sense of Providence. Even though it uses religious trappings, it is disconnected from actual religious practice.

Back when I taught Intro to Sociology, I had a lecture on Bellah. Drawing from Durkheim’s definition of religion as “a unified system of beliefs and practices relative to sacred things…”, I argued that Bellah was defining the functional approach to religion. Form is more important than substance. That vague form bound us together as a society, I argued.

I should note here that in Trump 2.0, there is no interest in promoting a generalized civil religion. His claims to protect (conservative) Christians and “bring God back” are anything but unifying.

This is why Kaylor and Underwood wrote the book. Because they are classical Baptists1 who believe in the separation of church and state, they are concerned with even the mild versions of state endorsement of the Christian faith. They rightly take the view of the atheist who is continually confronted with God language. Does that person not have rights because they are a numerical minority in society? What about Buddhists or other faiths? What is their place in a pluralistic society?

At the end of the penultimate chapter, the authors write:

Reducing religion to political tribalism makes Christian faith appear unprincipled and hypocritical. The attractiveness of its ideas and values becomes overshadowed by its misuse and abuse for partisan ends. Maybe too many people are throwing the baby out with the bathwater, but clearly a lot of people no longer believe Christian faith is redeemable from the way it’s been used to commit political sins. To use the language of marketing, Christian Nationalism is bad branding that soils the entire American Church. While mainline protestants helped lay the foundation for the larger edifice, the worst offenses now emanate from other corners, but they still sully everyone’s reputation. Unlike the business world, this is not a problem that can be resolved by a logo refresh or a clever name change. To the extent that non-Christians equate following Jesus with strident politics and fringe viewpoints, it becomes more difficult for the gospel to gain a fresh hearing. (180)

This soft fusion of religion and country can be seen in full force across southern states from Louisiana to Mississippi to Arkansas to Texas. This past Sunday, the lower house of the Texas legislature passed a bill requiring a particular version of the Ten Commandments to be posted in public school classrooms (violating the fourth commandment while doing so). The bill is now under consideration in the Texas Senate and the Governor is sure to sign it if it passes. While there are sure to be court challenges before it takes effect, the past stance of the current Supreme Court doesn’t offer hope in terms of a fair consideration of the First Amendment Establishment restrictions.

That such legislation is seen as just endorsing community standards or reflecting the supposed foundations of our legal code is a perfect illustration of how church and state get blurred. And we mainliners have much to ponder and for which to repent.

I’ve been told that Beau is Disciples of Christ, not Baptist. The point about separation still stands.