On Monday the New York Times posted this story about a professor at New York University (NYU) who was terminated after nearly a a quarter of his students submitted a petition complaining about his Organic Chemistry class. The author of the Times piece made clear what she thought about this:

In short, this one unhappy chemistry class could be a case study of the pressures on higher education as it tries to handle its Gen-Z student body. Should universities ease pressure on students, many of whom are still coping with the pandemic’s effects on their mental health and schooling? How should universities respond to the increasing number of complaints by students against professors? Do students have too much power over contract faculty members, who do not have the protections of tenure?

Reactions to the piece followed the predictable patterns.

These Kids Today! They want something for nothing. They are underprepared. They see grievance around every corner. They demand to be placated.

These Immoral Universities! Always focused on the bottom line. They see faculty as impediments to be removed and not resources to be nurtured. They treat every disagreement as a PR issue to be managed instead of finding reasonable accommodation.

These Professors today! They think they’re prima donnas who don’t have to change with the times. They are royalty in their own classrooms demanding respect and admiration. They think their special status allows them to behave however they want.

You have to make it past paragraph twenty in the article to find some nuance to the Kids Today argument. There had been a petition regarding the class two years ago (30 of 475 student signed). There were issues with internet access and later problems with cheating on exams. Professors responded to the cheating by lowering grades, critically important in a “weed out” class like Organic Chem.

Professors seemed okay with Organic as a gateway course. A colleague of Dr. Jones, Kent Kirshenbaum, is quoted in the article:

“Unless you appreciate these transformations at the molecular level,” he said, “I don’t think you can be a good physician, and I don’t want you treating patients.”

But is that really true? Does a diagnostic physician think about Organic Chem when treating a patient? And if it is true, how does the institution justify putting 375 to 420 students in the class? This would simply guarantee that a certain percentage would not clear the gateway to continue their premed pursuits.

Oh, and it’s important to remember who these students are. While I don’t have data on just the Organic Students, we can infer quite a bit from NYU students in general. According to an article by NYU’s independent newspaper, Washington Square News, the acceptance rate at NYU for fall 2022 dropped to 12.5%, less than half of what it was five years earlier. So seven of eight applicants don’t get in. And those who do? Their median SAT score was 1550. The average high school GPA was 3.70. While a fifth of the new students are first generation students and two-thirds of domestic admits were students of color1, they still met rigorous admissions standards. In any case, general assumptions about "today's college students" don't fit a highly selective institution like NYU.

Here’s another complicating factor. While Dr. Jones wrote an innovative textbook that changed pedagogy in Organic Chem, that was back when he taught at Princeton. The second edition came out in 2000. My attempt to figure out when the first edition appeared was unsuccessful. Jones had retired from Princeton in 2007 and had been teaching ever since at NYU on a series of annual contracts (which is why normal tenure protections weren't involved).

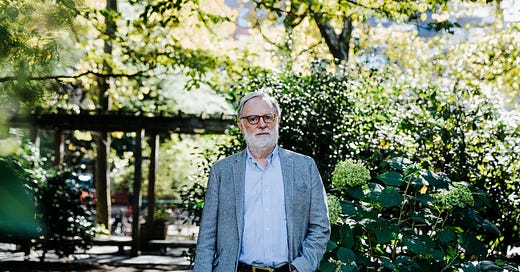

Taking the risk of being called ageist, I’ll point out that Dr. Jones is 84. His sophomore students would not been alive when that second edition of the textbook was published. Relating to students, especially those who are struggling, requires a certain degree of empathy and connection. I think the multiple generation divide provides part of the backdrop to the story.2

This is further acerbated by a perception of dismissive or demeaning comments toward students. From the petition:

“We are very concerned about our scores, and find that they are not an accurate reflection of the time and effort put into this class,” the petition said.

The students criticized Dr. Jones’s decision to reduce the number of midterm exams from three to two, flattening their chances to compensate for low grades. They said that he had tried to conceal course averages, did not offer extra credit and removed Zoom access to his lectures, even though some students had Covid. And, they said, he had a “condescending and demanding” tone.

There is no easier way to make students give up that to talk down to those who “don’t get it”. They are simply going to stop asking for help. Until, of course, they have to write a petition to the administration.

It’s like this classic scene in 1973’s The Paper Chase. Professor Kingsfield confronts first year law student James Hart, telling him “Here’s a dime3. Call your mother and tell her there’s serious doubt about your becoming a lawyer.” In the Hollywood version, such treatment makes James Hart work just that much harder to prove his worth and show Kingsfield that he could cut it. In real life, lots of students just quit.

Here’s one final complicating factor this story: the assumptions made by administrators. Early in the story, we read of the memo the director of undergraduate studies of the chemistry department sent to Jones.

Marc A. Walters, director of undergraduate studies in the chemistry department, summed up the situation in an email to Dr. Jones, before his firing.

He said the plan would “extend a gentle but firm hand to the students and those who pay the tuition bills,” an apparent reference to parents.

University officials had also taken the remarkable step of allowing last spring’s petitioners to retroactively withdraw from the Organic class.

This is a perfect example of what’s wrong with “the student as our customer” motif. This argument focused on maintaining satisfied customers and resulted in a never-ending series of “How did we do?” surveys, especially in support areas like financial aid or the business office or the cafeteria. But the student as customer argument also showed up when students would say “I pay your salary.” or “I pay tuition to get this credential.”

I spent the last half of my career railing against this motif. Faculty members are not producers who give a product to students who then consume them. Students aren’t “buying” what we’re “selling”.

The faculty student connection is best described as an expert-client relationship. I have a certain expertise in the sociological understanding and students come to me to develop and nurture their own. Consider the relationship between a personal trainer and a client.4 The client has certain identified goals and the trainer develops strategies to help the client in pursuit of those goals. Same goes for a financial advisor or a spiritual director.

The successful expert-client relationship depends on having all the things that were missing in the NYU story. A teaching environment small enough to attend to individual needs. A belief in the potential success of the client. Affirmation that the expert understands the client’s struggles and can be trusted to find the best way through them. And a system designed not to wash people out but to help them succeed.

This story in Inside Higher Ed on Tuesday documented the impact of gatekeeping classes on students of color, disproportionately pushing them out of STEM classes.

At my 50th high school reunion on Saturday, I had several conversation that revolved around that one professor in college who was unrelatable (due to age or language or demeanor) that was a contributing factor in a students’ struggles in college or abandonment of a degree altogether.

It was 1973 and we could make calls on things called pay phones using small coins called dimes that were worth 10 cents.

Or so I’m told, having never been either a personal trainer or the client of one.

Out of class and can't resist one more response. (Sorry!)

This paragraph portion is superb: "... A teaching environment small enough to attend to individual needs. A belief in the potential success of the client. Affirmation that the expert understands the client’s struggles and can be trusted to find the best way through them. And a system designed not to wash people out but to help them succeed." ... Amen!

I teach physics to pre-meds, engineering majors, physics majors, and math folks. I have no doubt that in time the details of what I teach will be gone from their minds. The purpose of my class is to help them embed some big ideas into their mind (Newton's Laws, energy and its conservation, types of waves, etc etc) show them how a physicist thinks and analyzes a system and help them gain skills in problem analysis. I'd rather my physician have skills at problem solving skills, an appreciation of their own fallibility, a desire to solve a puzzle (my health dilemma) , and the ability to seek out new information to help solve the puzzle. Hopefully education gets most of our doctors to this place.

One final thing. Sadly, everything in the USA is now a commodity, dollars run everything. Politicians serve for the perks and the pension. There are hundreds in an Organic or Physics classroom at Big State University to minimize cost. Most of the hundreds in Organic are there not to learn Organic, but because med school requires it. And most (not all) seek med school because it's a well-defined profession parents and students understand that leads to dollars and a nice retirement account in the long run. Our universities are slowly becoming professional schools for a reason...

Have a blessed day. Thanks again!

Superb John! I want to write more but have to head to class... let me say a few things quickly.

"But is that really true? Does a diagnostic physician think about Organic Chem when treating a patient? " Good question John--it is not true. The diagnostic physician has patients in the waiting room and must process the one before him or her expeditiously. The doctor relies on the Organic skills of the pharmacological community as they develop and test drugs, etc.

The concept of "weed out" courses has always bothered me. A course is a season of student development in a subject area. The difficult part is that our system of education demands a letter grade be assigned, and this is a subject worthy of a long discussion.

Thanks again!