Political Polarization (4): Don't Believe What They Tell You

Broadcast Media, Social Media, and What to Do About It

Shortly after we were married in the late 1970s, my wife got a job doing soil analysis for a farm consulting firm. The owners would travel to huge farms and collect samples, which my wife would analyze to determine Ph and phosphorus levels. These would get turned into maps to tell the farm owners how to best treat their crops. A few months after she started work, I got added on as a part-time worker.

We worked in the basement of a house-turned-office running tests on little bags of soil samples. The radio was always on. The local station devoted part of the day to a call-in show. One regular caller always raised concerns about the Council on Foreign Relations, The Trilateral Commission, and the dark forces that were controlling our lives. The moderator called him “the CFR Kid” (or else we did — its been 45 years!).

In retrospect, the CFR Kid seems almost quaint. According to a report from the Center for American Progress, there are now over 1,700 talk radio stations in the country, the vast majority of which are conservative in their politics. Conservative talk radio provides the background noise for small shops, farmers, and office workers across the country.

Attempts at progressive versions of talk-radio have generally failed to draw a sustainable audience. The CAP analysis showed that there were 2,570 hours of conservative talk radio broadcast each day compared to 254 hours of progressive talk radio.

National syndication and media consolidation has allowed a uniformity of voices. This also has the effect of nationalizing issues, drawing voters into larger cultural and petty political fights to the neglect of more local issues.

These same patterns can be seen in the realm of cable news. Long gone are the days in which television viewers shared their news from one of the three major networks.1 Today we have a plethora of viewing options and more people are tuned into something like HGTV than care about the daily issues of politics.

And yet there is a sense in which both conservative cable and progressive cable wind up responding to the demand issues raised by their viewers. It’s why Fox News will spend its time critiquing the foibles of a Democratic administration and MSNBC will focus on the latest outrage of the January 6 committee. CNN is for those who want to see a half-dozen people engaged in rapid fire overtalking about the conflicts of the day.

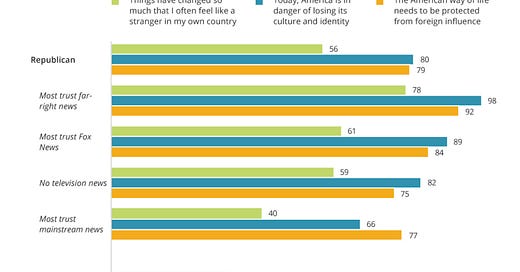

This matter of playing to the base has a differential impact on its viewers. The Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI) analyzed Republican and Democrat Views on American Culture, by Media Source as part of the 2021 American Values Survey. The results are interesting.

There’s a lot here to explore. Let me focus on only one of their items: “Today, America is in danger of losing its culture and identity.” The first thing to jump out is the difference between Republicans and Democrats with the former being 47 percentage points more likely to agree than the latter. Second, notice the stability of views among Democrats. Regardless of media source, agreement barely varies. Contrast that with what happens among Republicans. For those who only watch mainstream news, two-thirds agree with the concern about American culture. One the other hand, nearly all of those watching far-right news (Newsmax and OAN) agree.

Again, this may simply be demand effects. But even if the polarization pre-exists the viewing, its hard to argue that watching right-wing news sources isn’t making the polarization worse and increasingly intractable.

We can expand this analysis to include “print” and web sources. The AdFontes Media group recently updated their Media Bias chart. It places sources on a left to right axis and a fact to fabrication axis.

Again, we can see a structural imbalance here. There are sources further into the “hyper-partisan right” than into the “hyper-partisan left”. A second challenge is that, with the exception of the very top cells of the chart, facts give way to analysis, opinion, or hyperbole.

A 24-hour news cycle, even for “print” media, means a constant search for clicks. It’s easier to write analysis stories than detailed news stories. This is why we know more about how Joe Manchin feels about reconciliation than we know about what the components of the legislation are and what difference it would make. So we get horserace coverage and what will benefit President Biden’s approval numbers or the Republicans in the November election.

This is not a new problem. James Fallows wrote Breaking The News nearly 30 years ago and the issues he raised then (pre-cable) are still with us today.2

If they recognized that their purpose was to give citizens the tools to participate in public life, and recognized as well that fulfilling this purpose is the only way journalism itself can survive, journalists would find it natural to change many other habits and attitudes. They would spend less time predicting future political events, since the predictions are so often wrong and in any case are useless. They would instead devote that energy toward understanding and explaining what had already occurred and its implications for the future (which are different from guesses about who will win the straw poll in Florida). They would spend less time on sportscaster-like analysis of how politicians were playing their game, because they would realize that very few people care. Many journalists care, and their friends in politics care, but when they make this chat public they become as boring and irrelevant as any other group of insiders talking shop. They would feel less compelled to flock to the spectacle of the moment, in hopes of following the audience's fickle interest, and instead act as if the real challenge in journalism was that of making important matters seem sexy and intriguing. Broadcasters will always need to think about ratings and publishers will always need to think about circulation. But the evidence is clear: The "canny" tactical analysis on which today's political reporters pride themselves is not valued by the public. If it were, the press would have become more popular as it has grown more pundit-like (269-270).

If journalists focused more on what voters need to understand about policy proposals3 and how our lives would be impacted (for good or ill) it might just shift those demand preferences that push us back to the who-said-what arguments.4

Finally, there is the issue of social media. Many people today get their news from YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter. These sources are in many ways different from those described above in that they are driven by the algorithms that shape their audience while feeding the demand side.

In fact, the whole point of these sites (and others like them) is to get you to click on the next thing. To engage through clicks, through comments, or through sharing. Each time that’s done, the advertisers are pleased as you get pushed on to something else.

Dan Pfeiffer has an excellent chapter on social media strategies in Battling the Big Lie. Most importantly, don’t feed the trolls! There are lots of sites that will point out the latest ridiculous claim made by some figure (like Marjorie Taylor-Greene). It does no good to engage the claim as it simply increases the reach of her tweet. (Pfeiffer is a fan of sharing a screen shot of the claim instead of responding directly as to not feed the algorithm.) Be responsible in what you share. If you can’t verify it, don’t pass it along. When you find a correction made to misinformation, share that broadly. Keep things light and don’t let your anger push you in negative ways.

Pfeiffer ends the chapter by encouraging social media users to engage people In Real Life. Rather than taking on an ultra-conservative talking point, have a conversation about public issues with a couple of real people who might vote.

Ezra Klein has a similar take on real-life, local people as a solution to our polarization.

It's possible to make local and in-state news sources a bigger part of your media diet and thus make your local political identity more powerful. It's just a lift, particularly when those stories aren't being pushed at you by friends on social media or covered by the national publications you love. But there's a real reward from rooting more of our political identities in the places we live. First, we tend to live among people more like us, so the politics is less polarized. Second, the questions are often more tangible and less symbolic, so the discussion is often more constructive and less hostile. Third, we can have a lot more impact on state and local politics than on national politics, and it feels empowering to make a difference. And fourth, even if your heart lies in national politics - Im a journalist who covers national politics, I get it - being involved in state and local politics will make you much more effective, both because it's valuable experience and because local officials eventually become federal officials, and they keep in touch with the people they've known along the way. When the next presidential campaign rolls around, the people they're going to want most as volunteers are the folks who already know how to organize in their communities (266).

In addition to my national news sources, I get an online version of The Denver Post each day. The DP not only has tons of local news, but it aggregates stories and op-eds from a variety of other sources. I also subscribe to the local Commerce City paper. I’m trying to learn who my city councilperson, state representative, and state senator are in addition to the candidates for Congress and Senate.

In addition, I’ve tried to combat polarization by following right-of-center newsletters and twitter feeds. I don’t always agree (I often don’t) but it’s helpful to see a reasonable argument made.

I’ve covered way too much ground in this newsletter.5 Each of the topics covered in the section of this piece likely deserve a long treatment on their own. I imagine I will return to these topics often in the months to come.

I read an opinion piece today claiming that the January 6 Committee hearings were unimportant because 75% of households watched the Watergate hearings in 1973 compared to only 13 million viewers for the Cassidy Hutchinson hearing last week. I can remember that nothing else was on television EXCEPT the Watergate Hearings.

Most of us now get the “print” publications digitally.

In addition to Fallows, three media analysts are Jay Rosen, Dan Froomkin, and Margaret Sullivan.

I still couldn’t tell you what’s in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Act except I know it garnered votes from both sides.

I miss the days of just having the local paper in the yard in the morning, and Walter Cronkite on my black-and-white TV. (I’m old enough now I’ve earned the right to pine for the good ol’ days.)

I was raised quite right-of-center, so that’s the news and radio that I gravitated to as it became available. Thank goodness I outgrew it- but it took a long time! You get sucked into that “us vs. them” or “sports-team” sort of mentality, as you’ve pointed out.

Thanks for the counsel “don’t feed the algorithm.” It’s easy to forget about that. I was pleased to see that the new sources I now use are in the middle section of the data above. As far as Facebook and Twitter go, if it were up to me neither would exist. I’ve never done Twitter, and I canceled Facebook some years back because (for me) it was useless and a waste of time and energy.

There’s much in your essay above to digest. Thank you! I’ll have to read this again later,