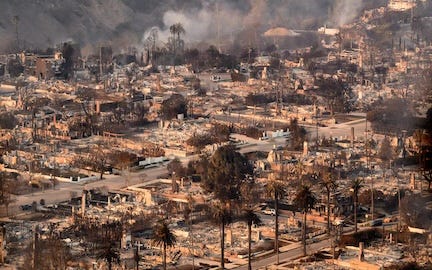

Watching the ferocity of the Los Angeles area wildfires has seemed like a disaster movie. But it’s real. As I write this, over two dozen have been confirmed dead, over 12,000 structures have been destroyed, and between 150,000 and 200,000 people have evacuated. The scale is hard to fathom.

We spent a year in the area fifteen years ago while my wife was teaching at Azusa Pacific. We lived in Arcadia, next to Pasadena. The Santa Anita racetrack, less than a mile from our apartment, is being used as a staging area for rescue and response operations. Pacific Palisades is about an hour east of where we lived. Altadena is about half an hour northeast.

I have former students who lost their homes. I have friends who suffer alongside their friends. Still others not only evacuated and returned home, but their go bags are still sitting packed by the front door in anticipation of the next evacuation order.

As I was reflecting on the devastation this weekend, my mind drifted to Kai Erickson’s Everything In Its Path, the story of the 1972 Buffalo Creek flood. When I started teaching Intro to Sociology in the early 80s, I always did a lecture that used a summary of the book that appeared in a sociology reader.

The lecture, as I remember, was an illustration of the fragile nature of culture and community. The lessons from Buffalo Creek resonate today.

Buffalo Creek was in the heart of West Virginia coal country and numerous villages dotted the expanse of the hollow. Many of the residents worked for the Pittston coal company. Pittston maintained slurry dams containing byproducts of their strip mining operations. One of the dams failed which caused two others to fail. Without any warning, flood waters 30 feet deep came rushing down the valley wiping out over 500 homes and killing 125 people (out of a population of 5,000).

Erickson’s book1 documents the longer term impacts of the disaster. He writes:

I am going to propose, then, that most of the traumatic symptoms experienced by the Buffalo Creek survivors are a reaction to the loss of communality as well as a reaction to the disaster itself, that the fear and apathy and demoralization one encounters along the entire length of the hollow are derived from the shock of being ripped out of a meaningful community setting as well as the shock of meeting that cruel black water. (194)

In addition to these psychological dynamics there is, of course, the physical dislocation.

The symptoms that make up the disaster syndrome, then, are the classic symptons of mourning and bereavement. People are grieving too for their lost friends and lost homes, but they are also grieving too for their lost cultural surround; and they feel dazed at least in part because they are not sure what to do in the absence of that familiar setting. They have lost their navigation equipment, as it were, both their inner compasses and their outer maps. (200)

What was once thought to be a safe and relatively stable — even if hard — way of life now seems open to question. Even a belief in one’s safety comes up for grabs.

The major problem, for adults and children alike, is that the fears haunting them are prompted not only by the memory of past terrors but by a wholly realistic assessment of present dangers. We noted earlier that the physical terrain of Buffalo Creek seems less reliable and less benevolent than it did in the past, and this is no trick of an oversensitive imagination. (238)

It’s early yet in the story of the Los Angeles fires. But I think we can anticipate many of the traumas that Erickson describes. The Washington Post had this story yesterday describing how Los Angeles residents think they may likely be next, that future fires are bound to get them.

Repairing the infrastructural damage in the communities of Palisades and Altadena will be long and very costly. And that’s not even considering the insurance crisis, the realities of climate change, and the regular occurrence of Santa Ana winds.

But as hard as it is to imagine, the repair of the social infrastructure will be much more difficult. And it is much more important than the physical structures.

As I no longer have the sociology reader, I just bought the book.