The Challenge of our Information Infrastructure

Small-d democracy and the need for a shared story

This is the second of my posts this week on the challenges facing our political institution. I mean much more than the president, congress, governors, and state legislators. I’m thinking about the political institution in its sociological sense. The structures and dynamics that enhance or inhibit our shared decision making as a society.

Monday I tracked Robert Putnam’s ideas about the decline in joining behaviors and the resulting loss of the social capital that binds us together. In the beginning of his book Our Kids, he describes growing up in Port Clinton, OH in the 1950s. He says that they had rich and poor but it didn’t matter because they were connected. The children on the playground were “Our” kids in a sense of shared responsibility. He contrasts that with more recent data where people are looking out for “Our” kids in terms of making sure immediate offspring have a leg up. The implication is that those who aren’t “Our Kids” are someone else’s problem.

As I wrote on Monday, he traces some of our collective loss of social capital to television. The more we watch, the less we have time for voluntary associations. Today, I want to examine a similarly devastating problem: the breakdown in our information infrastructure.

In a recent newsletter, Charlie Sykes quoted something he had written for The Atlantic back in April. He was making a point similar to Putnam’s, drawing from Neil Postman’s Amusing Ourselves to Death.

Four decades ago, Neil Postman prophesied an apocalypse of moral idiocy in the age of mass media. “When a population becomes distracted by trivia,” he wrote, in Amusing Ourselves to Death, “when cultural life is redefined as a perpetual round of entertainments, when serious conversation becomes a form of baby-talk, when, in short, a people becomes an audience and their public business a vaudeville act, then a nation finds itself at risk; culture-death is a clear possibility.”

Postman was prophetic, but he couldn’t have had any idea how bad things would get in the age of Donald Trump and Twitter. Faced with Trump’s behavior, America’s norms of decency and truth proved to be far more fragile than many of us imagined.

Postman wrote about the way the entertainment economy demands our eyeballs. And he was writing of the time when there were three evening news broadcasts seen by most of the country. Network television shows were appointment viewing and discussed the next day. Today we have hundreds of television channels, multiple news sources, a dozen or more streaming services, several sports channels with betting, multiple social media apps, and millions of videos available whenever we want. There is no shared experience.

In my old WordPress blog, I once wrote about another prescient figure: Ray Bradbury. One of the dynamics in Fahrenheit 451, the reason they were burning books, was because people were tuned into watch “the family on the wall”, a proto-reality program like The Truman Show. He even imagined the need for 98-inch wall-sized televisions.

These changes, like those Putnam described, do real damage to our small-d democratic lives. The Norman Rockwell image of the New England Town Meeting doesn’t work when everyone is distracted by so much requiring our attention.

This data comes from a Pew study conducted last April. It would have been helpful if they had also broken down which journalists and news organizations they were watching. But the telling factor here — related to the 2024 election and even more so to the ongoing health of our political institution is here in the age breakdown.

Less than half of young people reported getting their political and election news from news media. The figure for Gen X is still around two-thirds and for us Boomers, just over three-quarters.

Look at the other alternatives. I assume that the “none of these” category is a combination of those who have some other category or who just don’t follow political news. That’s just over one in five for Millennials and just under that for Gen Z. For this latter group, a third say that they get their news from friends, celebrities, or random strangers.

I’m a high news consumer. My morning breakfast routine involves reading updates on higher education, opinion and news summaries from the Washington Post, updates on religion news and data, a handful of newsletters, and the Denver Post. I follow news updates on BlueSky and watch Chris Hayes Tuesday through Friday. I have a variety of podcasts I check in on periodically when walking the dogs or driving.

But I’m clearly abnormal. And that matters.

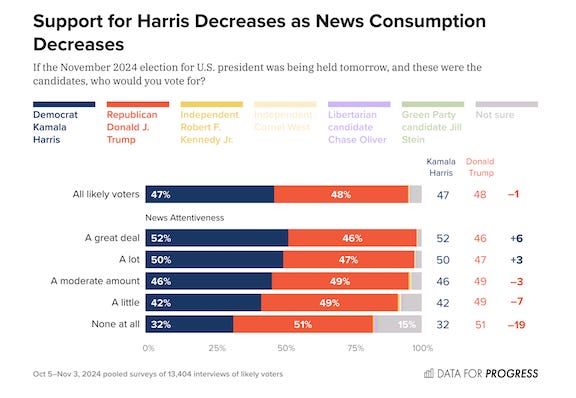

Consider this data compiled by Data for Progress. They analyzed aggregated fall election polls and looked at who voters supported as a function of how much they paid attention to the news.

It would have been great to have broken this data out by party. It may simply be that Democrats pay more attention to the news. But I think this is a bigger challenge. For those who were paying anything less than “a lot” of attention to the election, Trump was favored handily.

So what do we do? What should change in our media landscape to appeal to those who aren’t engaged with the media? Some of this is related to lack of trust in the media and other institutions — which I will address on Friday. Some is related to the standard way news coverage comes to us, as James Fallows observed decades ago in Breaking the News.

In the weeks since the election, I’ve been examining my news intake. I’m finding opinion pieces in the Post or the Times or AP to be singularly unhelpful. You can count on right-leaning op-eds saying one thing and left-leaning op-eds saying another. Even when you have a group dialogue as the Post has started doing, they often talk past each other. Even the straight news is frustrating. The first few paragraphs of a story may tell of some new development but the last half of the story is a rehash of how we got here or how various political figures respond.

Stories about families struggling with increased prices in the midst of strong macroeconomic factors aren’t particularly helpful as they provide a litany of complaints taken at face value with little analysis. Far too many stories have been about how grocery costs have tripled (unlikely) or gas is out of control (it will be under $3 soon).

There aren’t stories about how prices are about to go down in light of Trump’s election. Because they aren’t going to. Nevertheless, there will be plenty of stories about economic optimism and the hopes that prices will return to 2018 levels (they won’t).

In her excellent book, Strangers In Their Own Land, sociologist Arlie Russell Hockschild wrote about how people have a Deep Story. She describes it like this:

A deep story is a feels-as-if story — it’s the story feelings tell, in the language of symbols. It removes judgment. It removes fact. It tells us how things feel. Such a story permits those on both sides of the political spectrum to stand back and explore the subjective prism through which the party on the other side sees the world. And I don’t believe we understand anyone’s politics, right or left, without it. For we all have a deep story. (135)

I’ve thought a lot about mechanistic fixes to our information infrastructure problem. Maybe we need non-profit newspapers (we do). Maybe we need even more long-form SubStacks (debatable). Maybe we need progressive versions of Joe Rogan’s show (to what end?).

At the end of the day, what we really need is for all media sources — newspapers, podcasts, cable news, TikToks, SubStacks — to have a commitment to telling a Shared Deep Story. Yes, we need stories of the lives on rural workers, urban families, evangelicals, atheists, the wealthy, the young, those of us over 70(!), young men, trans women, and any other subsegment that they come across.

But they can’t stop with just telling the story of the struggling family or the hedge fund manager or the undocumented immigrant or the single woman in New York. What we need is for all of us, writing or podcasting or reading news, in whatever our chosen venue, to recast those stories into an amalgam.

Because why the “subjective prism” may feel justifying based on one’s particular group, focusing too much on that only fosters division and misunderstanding. But showing how those stories come together in a larger tapestry is key to our small-d democratic lives.

It’s a dream, I know. But maybe if the news was about that Big Story, people might just turn off the home remodeling show to see what’s going on.

Even if the rest of the media won’t be doing that, I’ll be trying in my own little way here on this SubStack.

John - appreciate your thinking on this and I wonder what are some examples of this deep story in action? One that comes to mind that exerted a lot of rhetorical force in this election, is the deep story of the "economy" (which you eluded to). Is that a deep story in at least a loose way and what might be the sources for reviving a more solidarity oriented deep story around this "household of exchange" (Oikonomia) that profoundly shapes our lives?

Some food for thought here comes from a paper by Lubos Pastor and Pietro Veronesi at Chicago Booth School of Busines where they created a simple model that predicts every election since 1927 on the basis of whether the economy was good or not (and the results are counterintuitive). Would love to hear what you think: https://www.chicagobooth.edu/review/the-economy-has-been-great-under-biden-thats-why-trump-won

Podcast interview: https://www.chicagobooth.edu/review/podcast/this-100-year-old-pattern-explains-trumps-victory

(Full disclosure: I work at Booth.)