I got home last night from having driven to Salt Lake City and back for the annual meetings of the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion1. Each year, the conference brings together social scientists and some religious leaders for a consideration of a variety of topics. Some of these are plenary sessions in a large ballroom. Some are “author meets the critics” sessions where recent books in the field are discussed by a variety of scholars with a response from the author. The vast majority are smaller breakout sessions where attendees chose a topic of interest to hear presentations and have discussion. I’ll share more of what I learned at the conference in Wednesday’s Substack.

I had organized a session on “The Future of Christian Universities”. I asked friends from various institutions to reflect on situations on their own Christian University campuses, focusing on particular issues that had been central in recent years. I wrapped up by talking about themes in my book project. Our session ran from 9:00 to 10:30 on Saturday morning and so I was very pleased that we had about 40 people in attendance.2

Suzie Macalouso is a sociology professor at Abilene Christian University, a Church of Christ school. She reported on a survey that had been requested by the student life committee of their board (sociologists always get roped into these conversations — I did a big one in the mid-80s.) The survey reported on religious vitality and examined subgroup differences in light of diversity of denomination/none, race/ethnicity, gender, and athlete/non-athlete. The short version is that there were minimal differences among the subgroups except for minor differences around the nones. While there may have been some nonresponse issues due to it being a non-anonymous survey so the students could get chapel credits3, it still showed how vibrant the faith life of Christian University student can be. While she didn’t (couldn’t) explore this in her data, this is still significant because the challenges discussed in the next two presentations happen among Christian students as opposed to some imagined less religious group on campus.

Josh Tom and Jennifer McKinney are sociology professors at Seattle Pacific. I’ve written quite a bit here about the tensions at SPU surrounding LGBTQ+ policies, particularly in regard to hiring. Students and faculty had advocated for changing the hiring policy resulting in student protests and lawsuits. The Board on multiple occasions refused to budge. Josh and Jennifer reviewed the history of the conflict. Of particular significance was a “policy on human sexuality” that had been created in 2004. In the early part of the 2010s, the Board adopted the policy as official but never announced it had done so. As the policy cannot be easily found on the SPU website, fully 40% of faculty were unaware of its existence. Unsurprisingly, it is now used as the excuse on why things cannot change. A fairly positive development could be seen in the development of a working group of faculty, staff, and trustees4 that was charged with developing a “third way” that would allow SPU to change its policy while still remaining a Free Methodist school. A Church leader on the board shared the working draft with denomination leaders who then issued a denomination-wide policy precluding any consideration of change in LGBTQ+ hiring. Recently, SPU was in the news for an HR policy prohibiting advocacy materials outside office doors. Thankfully, this is not being strictly enforced, but that could change in a moment. The key takeaway from their presentation was that SPU had an informal structure that was affirming of LGBTQ+ issues while boxed in by a formal structure that denied them.

The third presentation about Taylor University was done by Hannah Evans of Springtide Research Institute and a Taylor alum. Last spring, word came down that English professor Julie Moore, an ongoing contract faculty member, would not have her contract renewed. Julie, a former HBCU professor, had used race as a centralizing theme in her composition class. Her course shell (what we use instead of printed syllabi) included a quote from Jemar Tisby’s The Color of Compromise (more below), although his book was not on the reading list. Hannah did a great job of placing Taylor in its socio-historical context. She noted that Taylor is only 14 miles from Marion, Indiana — the site of the last known lynching in America. Given the cultural context of rural Indiana, it tends to skew conservative in its politics. Hannah traced the history of the Black student organization at Taylor, noting that most students of color were international students. Still, there was interest and passion among many white students to deal with racial issues post-Ferguson. But administrators and trustees are more conflict averse. The president and provost both have such a history coming from Gordon and Cedarville, respectively. So, in light of the Grove City crisis over Tisby and the fact that Moore was non-tenured, they took advantage to purge their ranks.

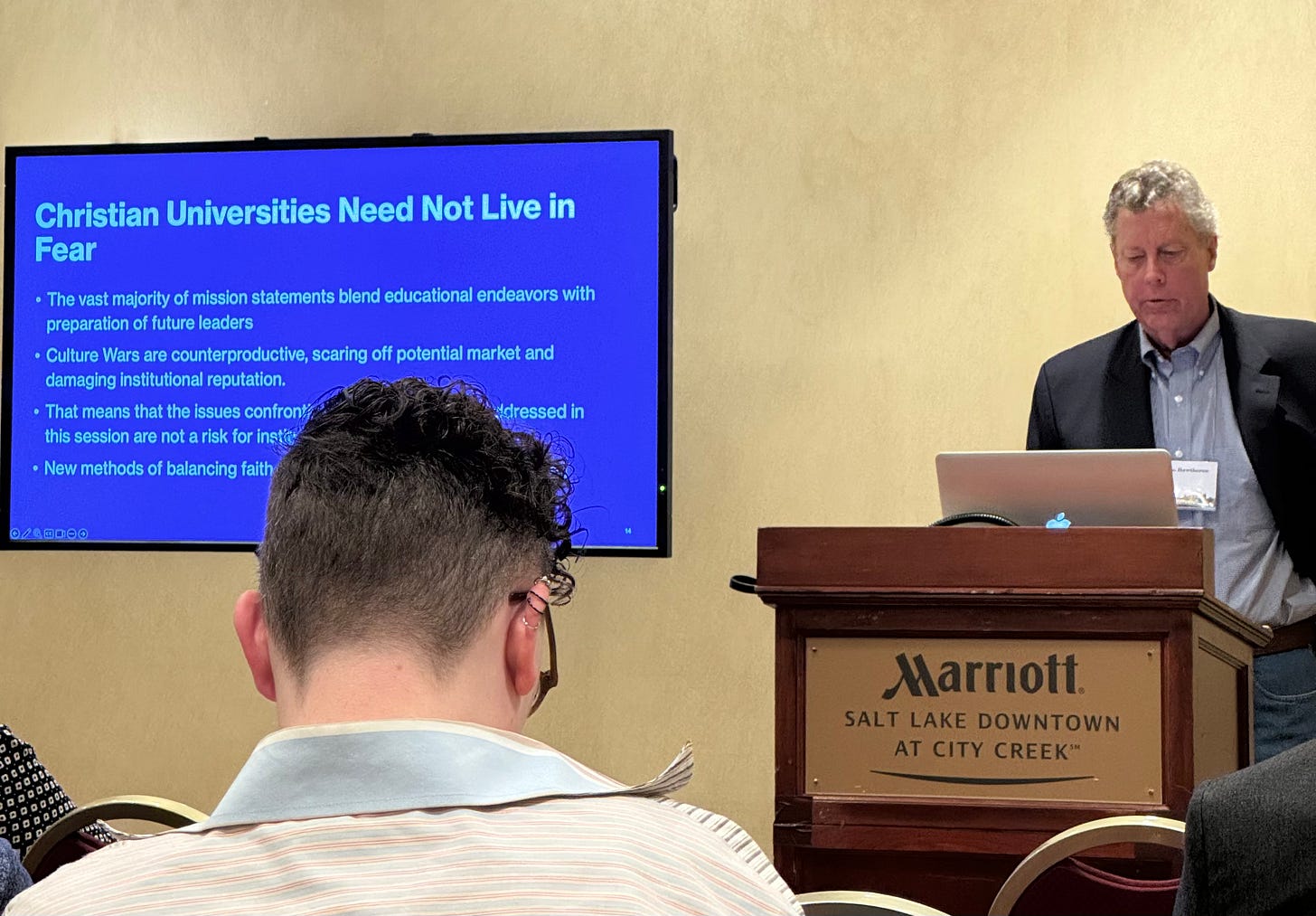

I started my presentation with the Grove City story which I addressed in the post above about SPU. To recap, a year after Jemar Tisby spoke in chapel on themes from his book, an alumni group started a petition stating that Grove City had “gone woke” and endorsing Critical Race Theory. A formal board committee was established six months later and presented a report saying that chapel speakers should be better vetted in light of university mission and values and recommended/required the dismantling of a number of diversity related topics on campus. After using Grove City as my intro, I reviewed an analysis of 30 Christian University mission statements. Doing a rough content analysis, I identified ten themes which I collapsed into four broad categories: campus characteristics (community, holistic education), contrast with external culture (separate from the world, Biblical foundations, denominational identity), academic life (integration of faith/learning, academic excellence, character formation), and future orientation (developing future leaders5). Even though mission statements might involve multiple themes, I catalogued the percentage of mentions by category. Academics was mentioned 32% of the time, Future leaders 25%, Institutional Characteristics 24%, and External focus 19%. From this analysis, I concluded that there is nothing in most Christian university mission statements that mandates continued Culture War battles like we saw at SPU, Taylor, Grove City, or ACU (although that wasn’t part of Suzie’s survey). Rather, we could potentially organize the various mission categories as follows:

This, of course, is the thrust of my book project. By beginning with the questions students bring with them and helping them truly wrestle with their difficulties, we would be preparing students to be the Christian leaders of the future. All of that happens within a strong commitment to being an Academic Community characterized by trust and celebration of diversity that sustains Christian belonging. If that were our focus, Culture Wars are not only unnecessary but inevitably counterproductive.

While we didn’t have as much time for audience discussion as I would have liked, there was tremendous support for what we’d presented. Some people commented that schools seems to be pushed rightward by trustees, donors, and churches and therefore all try to mimic the most conservative options available. I shared that according to PRRI, only 9% of 18-29 year-olds identifed as White Evangelicals in 2022. This suggests that finding another path is essential for institutions to thrive. Becoming more and more conservative (religiously, politically, and culturally) will simply appeal to a smaller and smaller segment of students.

Others pointed out the difficulty of promoting such thinking given the priors of their presidents and trustees (which I’ve written about here and here). That gave me the opportunity to make the argument which will make up the next chapter of the book.

It was a great conversation. Many said that it has been long needed. I hope that similar sessions will occur at future conferences.

Most of it was a picturesque drive but otherwise was right at the edge of my one-day driving limit (9 hours counting stops).

The room was set up to seat about 50 people and this was probably at least twice the attendance of most of the sessions I attended (not counting the plenaries).

My 1980s survey had the same challenges.

This is the kind of collaboration I’m calling for in the next chapter of the book.

Although they are unfortunately vague on how those leaders are developed.