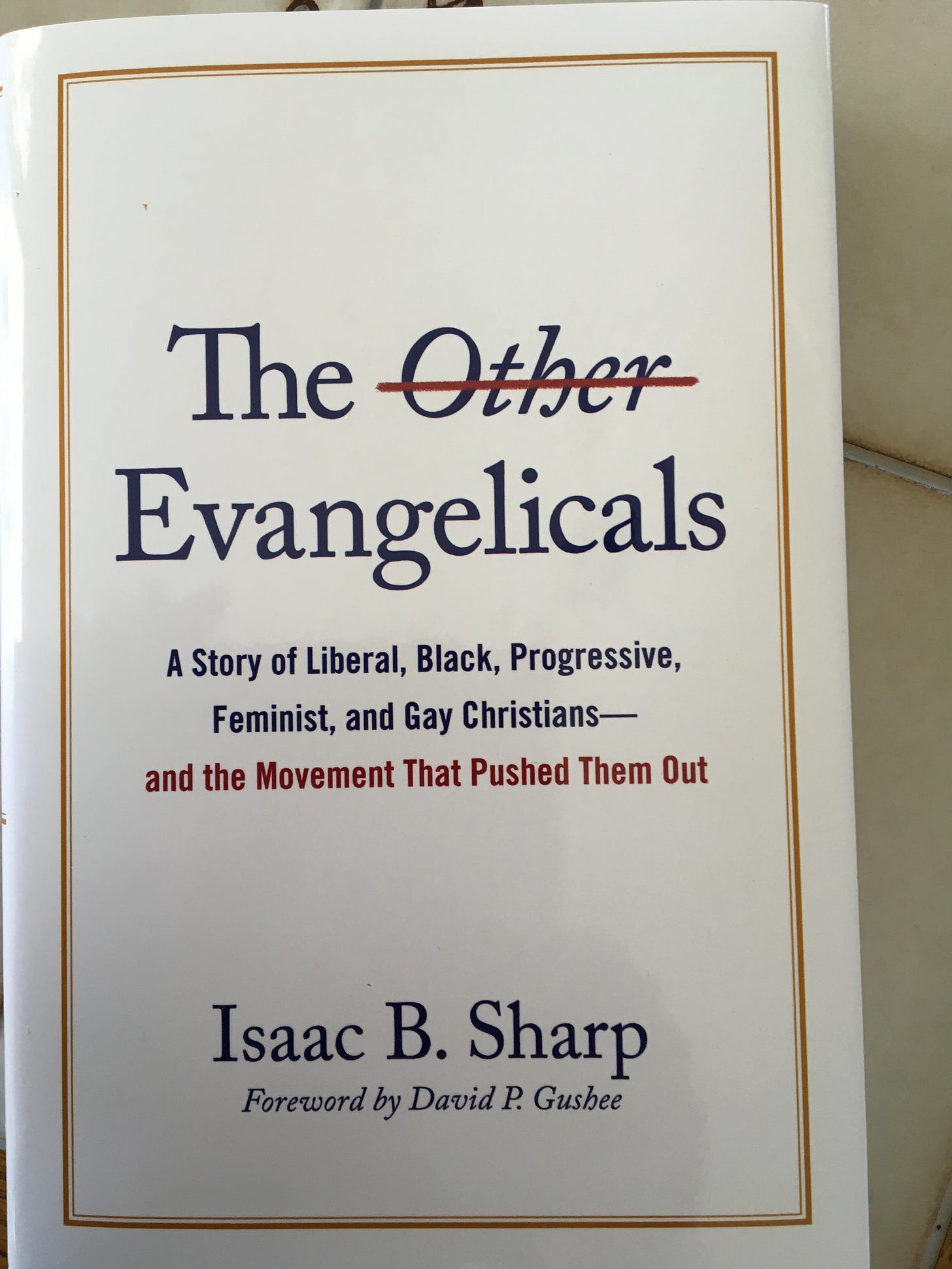

As I wrote on Monday, I’ve been reading Isaac Sharp’s The “Other” Evangelicals.1 I finished it yesterday and highly recommend it. If you’ve read John Fea, Kristin DuMez, Beth Barr, Molly Worthen, David Gushee, and a host of others, this book belongs on your shelf.

The heart of the book explores specific individuals who fall into particular categories: those who studied “liberal” methods of biblical criticism, black religious leaders, politically progressive leaders and periodicals, Christian feminists, and Gay Christians. Each of these chapters follows a similar pattern. First, he identifies exemplars of each of these movements and establishes what ought to be their evangelical bona fides. Second, he documents how the institutional establishment of evangelicalism redefines evangelical in ways that exclude them.

The end of his subtitle tells the story: the Movement that Pushed Them Out. The first generation of Evangelical Establishment in the early 1940s involved the founding of the National Association of Evangelicals, Fuller Theological Seminary, and Christianity Today. The second generation, as I see it, expands to include conservative (generally Southern Baptist) seminaries, the Gospel Coalition, and a host of books, periodicals, and radio programs. Each of these entities work to define the ways in which the “offending party” must fall outside the bounds of what it thinks is True Evangelicalism.2

Sharp describes this exclusionary practice in his conclusion:

When debates reached a boiling point, the uncomfortable reality of internal evangelical pluralism often resulted in an implicit or explicit ruling from the unofficial evangelical gatekeepers that one or the other core commitment, or interpretation of a core commitment, or implication of a core commitment was the preferred evangelical option (p. 271).

While reading the book, I kept thinking about the larger social currents in which these exclusionary tactics took place. This isn’t a critique of Sharp’s book — one has to circumscribe a project in order to finish it.3

So I want to zoom out just a bit from the True Evangelical decisions to set some context. First, the first generation Evangelical Establishment occurs in the period immediately preceding World War II. While not fully connected to all of the America First folks, the Evangelical Establishment is born in a period of intense national pride. European methods of biblical criticism might be fine for their more secularized societies, but Americans don’t need that stuff.4 Christianity Today editor Harold Linsell’s “biblical defense of the free enterprise system”5 occurs in the context of differentiating the US from “Godless Atheistic Communism”, so progressives are challenging America’s very identity. The urban unrest of the civil rights movement drew attention to the structural concerns surrounding racial inequality; far better to leave race issues on the level of personal prejudice and outright bigotry because those can be solved (theoretically) as “sin issues”.6 Christian Feminism arises in a Mad Men world and is rightly seen as a threat to the presumed order of things.7 Gay Christians, at first attacked from the lens of commitments to biblical inerrancy, become symbolically isolated once the AIDS crisis hits the community.

There’s another piece of this social context that is important to highlight: the role of talk radio. Last month, On the Media devoted three shows to the emergence of the form, specifically exploring the role of what became Salem Media. Katie Thornton starts with the emergence of AM radio as a venue for hearing Christian preachers. As the media network expands to more and more stations, it begins adding Christian talk and then political talk.8 In the last of the three episodes, Thornton interviews the Phil Boyce, senior vice president spoken word for Salem. He explains the vision of their programming.

Let me see if I can give you a little more on that. Salem's basic format, the format that started the company is what we call Christian Teach and Talk. It's basically an all Christian, all the time format that helps people accept the challenges of their life through a Christian worldview. Maybe you don't know this, but a lot of the Christian Teach and Talk listeners are conservative politically. Not all of them, but a lot of them are. And if you look at the Newstalk format, a lot of the Newstalk listeners are either Christian or Jewish or have some kind of a faith in their life. So I don't find there's any conflict or any disagreement between the two.

She asks him to elaborate on the Christian Worldview of Salem and he says this:

Well, there's nothing really in writing for that, but we believe that America is the greatest country on earth. And we should do everything we can to protect the Constitution, to help foster the conservative values that we think the country was founded on. You know, I can't give you a paragraph of something out of our handbook. I can just tell you that I know in my heart what it is, the chairman of the board Ed Atsinger knows what it is, our CEO, Dave Santrella knows what it is. And we think we're performing a really important job in America.

The upshot of this is that the Evangelical Establishment was predisposed to see the world through the lens of white middle class patriarchal structures9 and their commitment to inerrancy provided the means through which to defend their position. Since they controlled the official evangelical media organs, they could play the role of Gatekeeper as it suited them.

Early in the book, Sharp pays attention to the sociological contrasts on how evangelicalism operates. Christian Smith argues that the “embattled and thriving” subculture of evangelicalism allows them a great deal of coherence. James Davison Hunter, on the other hand, sees evangelicalism as engaged in cognitive bargaining as they attempt to react to contemporary issues in the modern world.

I’m clearly in the Hunter camp. I’d argue that the Other Evangelicals Sharp covers are as well. They attempt to reconcile new realities (biblical scholarship, race, gender, politics) within the evangelical framework. The Gatekeepers prefer the Smith approach.

But the Gatekeeper role has become increasingly limited. A plethora of alternative publishing houses have sprung up. The Internet allows alternative voices to pick up a following in spite of what the Gatekeepers think.10 Increasingly, the younger generation is demanding that these alternative perspectives be considered.

One of the byproducts of the social media shifts is that today’s Gatekeepers have become increasingly harsh and strident. The list of otherwise Christian leaders who attempt character attacks on innovators grows by the day. Naturally, their stridency only adds to the legitimacy of the alternative voices present.

As I said earlier, nothing I’ve written in the last half of this newsletter is limiting to Sharp’s argument at all. It’s a great book that helps us understand the historic pattern of Gatekeeping around how the powers-that-be defined capital-E evangelical. It also gives us grist for understanding how issues of race, gender, politics, and sexual orientation can potentially become part of that evangelical identity.

Actually, the Other has a line through it but I don’t have strikeout text available on here. Also, David Gushee pointed out recently that he doesn’t know how to read the strikeout.

When Sharp uses this phrase in the conclusion, my mind went immediately to the True Scotsman fallacy. If they believe X, then clearly they can’t be evangelical because everybody knows evangelicals don’t believe X (while denying that evangelicals believe exactly that).

The book is a shortened version of his dissertation.

I think Marjorie Taylor Greene said that on 60 Minutes.

Which stil shows up in some Christian University strategical plans.

As we see today, focusing on structural issues might make white folks “feel bad”.

Sharp includes this quote from Dallas Seminary president Charles Ryrie 1963 article in Eternity: “a woman may not do a man’s job in the church any more than a man can do a woman’s job in the home.” (!!!)

The role of Paul Weyrich in both sectors is remarkable.

Thanks to Kristin DuMez’s Jesus and John Wayne.

The late-too-soon Rachel Held Evans demonstrated how a social media presence could provide ways around the proverbial Gates. And the harder the Gatekeepers pushed, the more voices like Rachel’s flourished.