As it often does in relation to our national fascination with gun violence, this week the parody site The Onion shared this insightful tweet.

Undoubtedly, this post was prompted by a range of horrific events. Last month Ralph Yarl was shot and killed by a homeowner when he knocked on the wrong door. Two days later Kaylin Gillis was shot and killed by a homeowner when the car she was riding in pulled into the home’s driveway to turn around.1

The week before in Texas, Daniel Perry was convicted of ramming and shooting a George Floyd protester during 2020 protests in Austin. Perry had claimed he was in fear of his life because the victim had a gun. While he was sentenced to 25 years in prison, Texas governor Greg Abbott wants to pardon him on the basis of “stand your ground laws”.2

On May 1st, Jordan Neely was choked to death by Daniel Penny3 in a New York Subway car. Neely, a homeless man who regularly spent his days riding the subway and panhandling, was allegedly acting erratically while asking for food and money. Penny didn’t intend on killing Neely, but put him in a choke-hold (this is why Penny is charged with second-degree manslaughter).

The Neely-Penny story brings together the perceptions of the homeless as a threat, fears of riding the subways, the failure of mental health infrastructure, and our reliance on the criminal justice system to solve our social ills. This weekend David French wrote an op-ed in the New York Times identifying these systemic failures. While he stops appropriately short of valorizing Penny, the impression left by his piece is “what can you expect?”.

Others were not as nuanced. Greg Sargent and Paul Waldman noted that both Nikki Haley and Ron DeSantis had celebrated Penny as a “Good Samaritan”. DeSantis gave money to a GiveSendGo4 account in support. Marjorie Taylor Greene and Matt Gaetz both celebrated Penny’s action.

In his newsletter in the Philadelphia Inquirer, Will Bunch noted that this is not the story of the Good Samaritan.

It’s been a few decades since I attended Sunday school, so I went back and re-read this parable to see if I was missing the part of the story when the Good Samaritan grabs the traveler from behind, places him in a military-style chokehold and strangles him. If that sentence sounds absurd to you, then you are not a fan of politicians like Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis or a consumer of right-wing media like the editorial page of Rupert Murdoch’s Wall Street Journal. All of them are taking part in what looks to be a coordinated campaign to portray Long Islander Daniel Penny, the 24-year-old ex-Marine whose Manhattan F-train chokehold killed a homeless and mentally ill Jordan Neely, as the “Subway Samaritan.”

This use of Samaritan language got me thinking of laws by that name passed in many jurisdictions to protect a bystander responding to an emergency from future legal liability. The rationale is that it’s in the public interest for someone to help someone in an emergency situation without first wondering if they’d be sued.

Such laws arose in part as a result of social psychological research conducted fifty years ago. Bib Latené and John Darley conducted a series of excellent and creative research projects exploring why people didn’t get involved in bystander situations.5

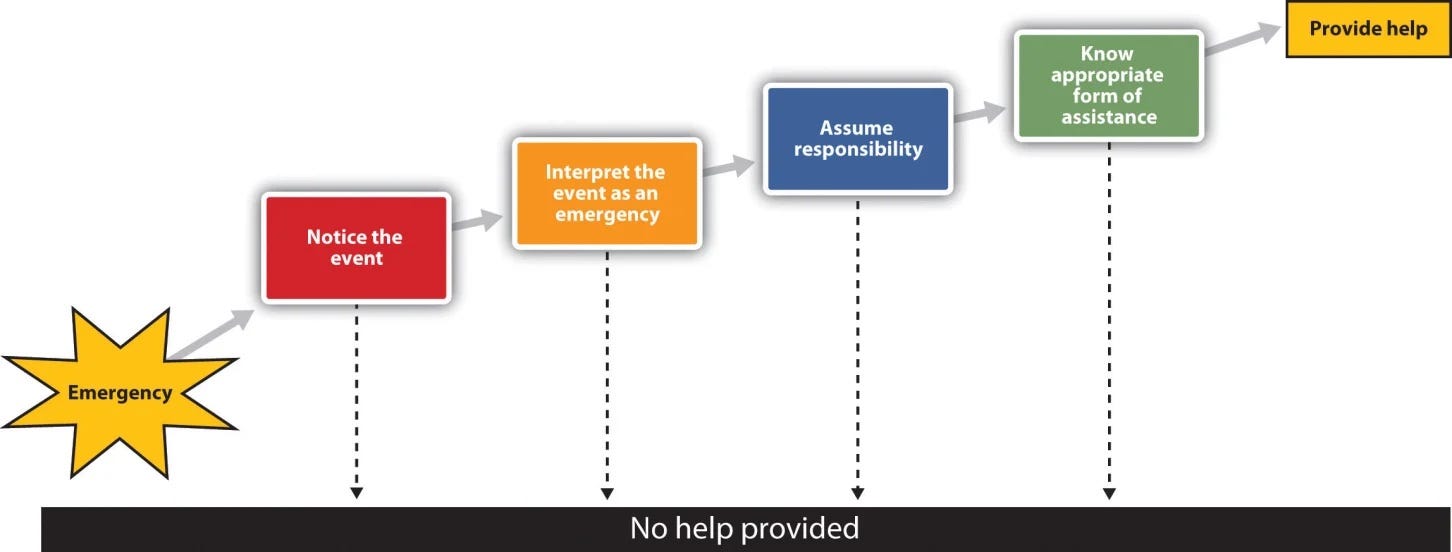

Summarizing their research, Latené and Darley developed a five-step flowchart identifying the steps involved in responding to an emergency.

First, the subject must 1) notice the event and 2)then determine it is an emergency. Next, the subject must 3) decide to take responsibility to act, 4) assuming some specific knowledge of how to react. If all conditions are met, they step in to respond to the emergency.

One of the key ingredients that inhibits helping behavior is ambiguity. If the situation is unclear as to what is going on, then identifying the emergency becomes difficult.6 That ambiguity is a key driver of diffusion of responsibility — if nobody else is panicked, maybe I’m misreading the situation.7

I think that the rise of a concealed and constitutional carry populace has had the effect of reversing the Latené and Darley model. Actors have prepared for the worst and trained (of sorts) on how to use their weapon. Given said weapon, they decide they must act, especially when they don’t know if it’s an emergency or not. Under this process, ambiguity makes action more not less likely. That’s what explains Kansas City and Upstate New York. It fits the Rittenhouse situation in Kenosha. I think it explains Penny on the Subway.8 It’s the message of the Onion tweet above.

Yesterday, on Chris Hayes’ Why Is This Happening? podcast, he rebroadcast an episode from Ryan Busse, a former gun industry executive. Busse explained how both the NRA and gun industry marketing moved from support of hunting to home protection to being ready for anything; including protecting yourself against the government or bad people.

Christine Emba, writing in yesterday’s Washington Post, reported on conversations she had with attendees at a gun show. They picked up the themes I’ve describing here.

Perhaps the most troubling aspect of gun ownership for “protection” is the sharp-edged individualism it implies: an every-man-for-himself mind-set. Institutions can’t be trusted, police will be unresponsive, and the government might one day turn on you. Your only obligations are to yourself and your family.

Individual fear becomes a greater priority than collective safety. Increasing the number of guns in the system will almost certainly spell death for others, but at least your gun will keep you safe.

Today University of Texas sociologist Harel Shapira reported on his research attending firearms classes. He notes that gun safety was an important criteria of the classes he attended and the instructors were diligent in making clear how dangerous guns could be. But there was also another message:

Instructors repeatedly told me that statistics about crime are meaningless when it comes to the need to carry a gun. It’s not the odds, I heard on numerous occasions; it’s the consequences. I have been taught strategies for avoiding interactions with strangers. I have participated in scenario training sessions in which students carrying guns loaded with plastic ammunition enact mock burglaries, home invasions, mass shootings and attacks by Islamic terrorists. Repeatedly the lesson was that I ought to shoot even when my instincts might tell me otherwise.

For example, in one scenario, an instructor pretended to punch someone I know and care about in the head. The instructor’s back was toward me, so I held my fire. Later, I told him that I hadn’t had enough information to act. Wrong answer. Being punched in the head can be fatal, the instructor told me, so there was no time to wait. I had never heard someone advocate shooting an unarmed person in the back. The instructor did it with a sense of moral, legal and tactical clarity and conviction.

No doubt because he is a sociologist, Shapira precisely followed the steps of the Latené and Darley model. He saw what was happening but wasn’t sure how to process the situation, so he held back. But that was wrong, according to the instructor. He concludes his piece like this:

The N.R.A. says that “an armed society is a polite society.” But learning to carry a gun isn’t teaching Americans to have good manners. It’s training them to be suspicious and atomized, learning to protect themselves, no matter how great the risk to others. It’s training them to not be citizens.

To avoid ambiguity, you have to be ready to act. This can turn what should be arguments into deadly encounters. This was made clear to me here in the Denver area recently when two Tesla owners got into an argument at a charging station and one shot the other dead.

When it’s all about the “good guy with a gun” stopping the “bad guy with a gun”, individuals never have any ambiguity about which one they are. And that will continue to fuel incidents like we saw in Kansas City or upstate New York or on the NYC subway.

These events are not meant to take anything away from our ongoing crisis of mass shootings in domestic violence situations or shopping malls or schools. Those have their own etiology.

There are striking similarities here to the Kyle Rittenhouse case in Kenosha, Wisconsin, except that Rittenhouse was acquitted.

The similarity in names of these two Daniels made it hard for me to remember which case was which.

This is a Christian version of GoFundMe.

For years, textbooks have said that this was in response to the sixties-era killing of Kitty Genovese in New York, where everyone assumed someone else called the police (this is called diffusion of responsibility). Reporting decades later showed that actually numerous people had called the police. But the research is still worthwhile.

I think the model works very well when considering the behavior of most of the other people in the subway car when Penny applies the chokehold to Neeley.

One of my favorite experiments in this category involved having a naive subject in a room full of confederates filling out a survey. Dry Ice is triggered to send smoke from under a closet door. The confederates don’t respond. Will the subject?

Perry’s situation is more complicated. He seems to have been hoping for trouble.