For all my years of schooling, there are two classes I regret not taking. One is Modern Philosophy, although teaching through Michael Sandel’s Justice for years has filled in some important gaps.

The other, far more significantly, is macroeconomics. As a sociologist naturally concerned about the drivers of inequality and what possible remedial steps we could consider, this has proven a terrible gap.1 I want to pose several questions and unpack them a bit. Hopefully, more economically astute subscribers can fill in the gaps in the comments section.

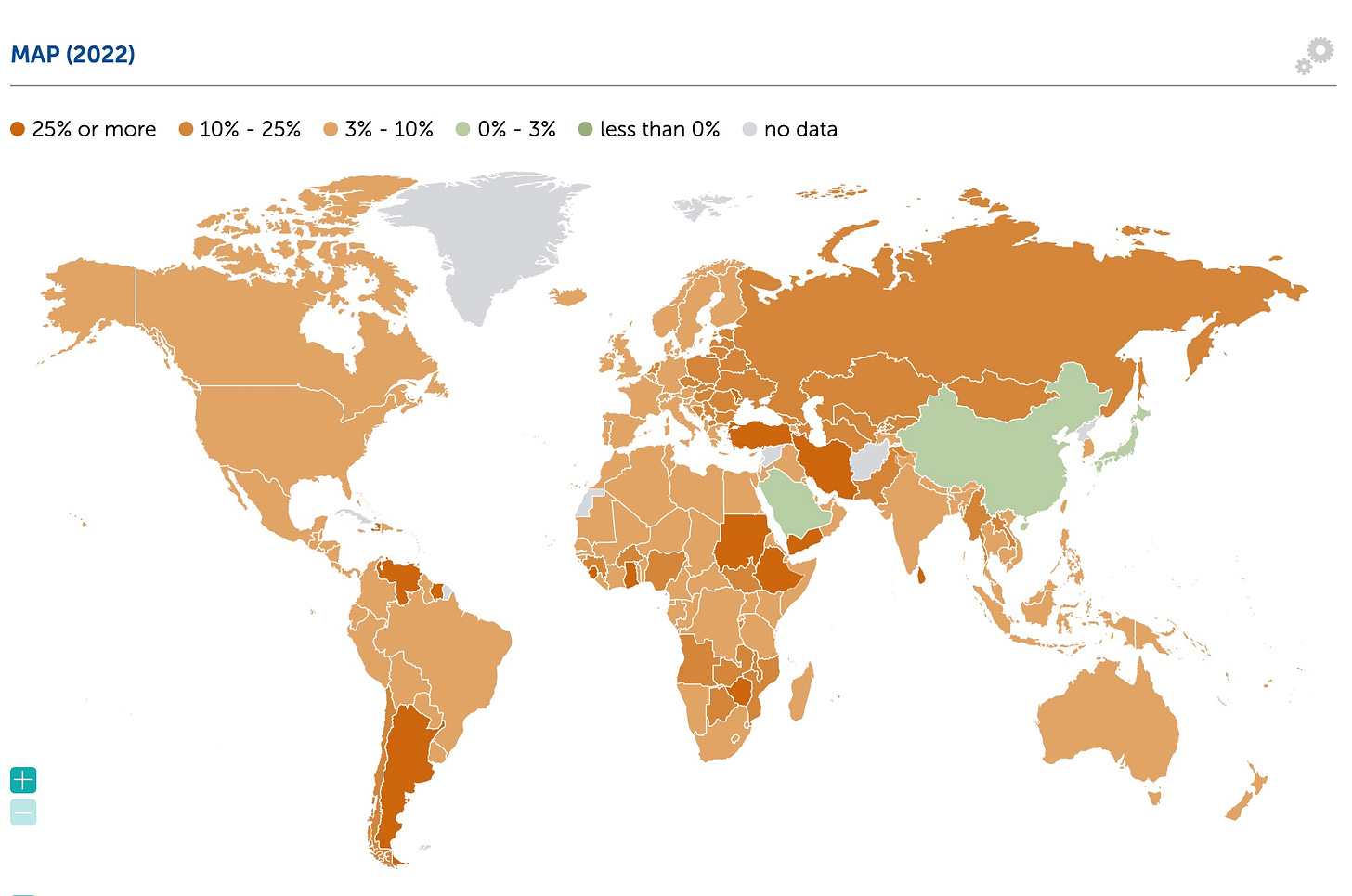

How have Multinational Corporations changed the global economic landscape? Whenever I got to the point in my Sociological Theory course where we discussed Immanuel Wallerstein’s World System Theory, my mind would shift from the political realm (where core countries exploit peripheral countries) to multinationals. It was probably my most depressing lecture as I argued that there was little that any nation could do to control actions by multinationals. Our more naive sense of political economy acts as if actions of the president or the Congress would shape these global entities. The truth is that they cannot.2 This is why the only way to evaluate our current inflationary pressures is from a global perspective. Consider this recent chart from the International Monetary Fund.

I’m not a fan of the wide spread in their legend (3 to 10, 10 to 25), but it is informative nevertheless. With the exception of China and Saudi Arabia, the rest of the world is in a similar place as the United States or else it’s much worse. If there are global supply chains facing inflationary costs, those get priced into US production.3 As much as politicians of both parties love to talk about repatriating supply chains, that’s not going to happen.

How does the Federal Reserve balance inflation and employment? The Fed has a mandate to control inflation while maximizing employment. In principle, the target is to keep inflation around 2%. That’s where things stood in late 2020. After over a decade of “quantitative easing” where the Fed kept the money flow open as we came out of the Great Recession, keeping interest rates near zero for the big borrowers, they started squeezing that supply. Then the pandemic hit and business as usual was not possible. When the economy opened up after the worst of the pandemic, it opened rapidly (unlike the recovery from 2008). This was complicated by supply chain challenges, and also because the CARES act and the American Rescue Plan put capital directly in families’ pockets (as well as temporarily supporting unemployment benefits and child tax credits). While that funding stream allowed consumers to buy goods (thereby helping businesses get back on a normal track), it also raised inflation as there was a surplus of money chasing limited goods. That’s not to suggest that we shouldn’t have taken those stimulative steps. The alternative, as Pete Buttigieg recently pointed out on Face the Nation, would have been economically disastrous. Yes, the Fed could have acted faster back in the first quarter of 2021 and certainly when Russia invaded Ukraine in the third quarter. But the Fed has limited tools. Their primary hammer, for when everything is a nail, is to raise interest rates. They’ve done this several times and are primed to do it again later this fall. Raising interest rates slows the housing market as mortgages are harder to get which lessens construction jobs which impact the surrounding market those workers would have spent their money in. We continue to see robust job growth, even in the face of “quiet quitting”, which suggests that there are other factors the Fed ought to be considering.

Do the Stock and Bond Markets Care about anything other than self-interest?

Back in the 1990s, I remember reading Bob Woodward’s The Agenda. It was the story of Bill Clinton’s first year in office and the passage of his signature middle class tax cut. I no longer have it but what sticks with me is that Clinton triangulated his tax plan with support for the Bond market. He could get away with raising taxes if he could make sure that the financial markets did well. That way, even though the rich paid more taxes on income, they’d benefit from the market over the long run. During the Clinton years, the Dow Jones4 grew by nearly 230%. That focus on the markets as “the economy” has only gotten more pointed over the last two decades. Growing the market seems to be an end in itself rather than the investment vehicle that could benefit the entire economy.5 For example, when the September employment numbers came out the first week of this month, the markets tanked because of fears that more employment meant that the Fed would be more aggressive in raising interest rates. The separation of “wall street” and “main street” is one of our most pressing problems.

What Drives Inflation?

Talk to any conservative pundit or politician and you will hear them quoting Milton Friedman that “government spending causes inflation”. This was repeated multiple times by Senator Mike Lee in the Utah Senate Debate I referenced in my last newsletter. It was also quoted directly by the Republican candidate for Colorado state treasurer (who apparently is a big fan of Lee’s). This represents the anti-government bias I wrote about recently. Again, it’s not that simple. Forbes analyzed the data and argued that in the current case, the stimulus funding may have had a limited impact on inflation. Yet those funds were largely put into circulation by the second quarter of 2021 so it’s hard to see their follow-on impacts. Nevertheless, conservative critics (like the above-mentioned treasurer candidate) argue that families are spending $950 per month more than they were in January of 2021 due to inflation. That claim (also repeated by Senator Lee) caught me up short. The median income in Colorado is just over $72,000 so, if true, that suggests a 16% reduction in purchasing power. I had to do a detour to find out what they were talking about and discovered that this is an estimate from the Republicans on the Joint Economic Council of Congress. They estimate the increased monthly cost of food, housing, transportation, and energy relative to January 2021 and then add these categories together. Of course, while food costs, gas prices, and electric bills are real drivers not everybody buys a car or buys a new house or rents a new property each month. While these legitimately are part of inflationary pressure, they aren’t what families experience. Eliminating the housing and transportation categories reduces that “monthly increase” by over $530. It’s still a problem but it’s best to use logical thinking rather than alarmist numbers.

What’s happening with consumer spending?

This whole newsletter was prompted by three stories that appeared on the same page of yesterday’s Denver Post. The first explained global inflation by looking at how supply issues have affected French bakeries. One chain is having to raise their prices by an entire dime! The subhead for the story reminded us that “the revolution started over the price of bread.” Nobody is saying that this price increase is easy but nobody is really saying it’s prompting revolution either. The second story described how conglomerates like Nestle and Proctor & Gamble are raising prices by nearly 10% this quarter. They are doing so to make sure that their profit margin matches prior that of prior years.6 From these stories (and hundreds like them) we'd all assume that consumer behavior would be squelched. That's why the third story caught my attention. It discussed how consumers will approach the holiday purchasing season. The story quotes a survey that says that 20% of consumers will spend less this season, an increase from prior years. But that means that 80% of consumers will spend the same amount or more! Consumer behavior continues to be positive even though credit cards are getting more expensive thanks to the Fed.

Why can’t we have new approaches to economic policy?

I can’t end this without sharing a clip that appeared on Twitter yesterday showing pundit (and former white house economic advisor) Larry Kudlow cheering the Liz Truss administration back in September for their bold tax cut and austerity budget. The fallout from that same budget yesterday caused the prime minister to resign after 44 days.7 Robert Reich has argued for years that economic investment that benefits the working and middle class causing them to spend more in the production (rather than investment) economy. That may well lead to inflation remaining higher than the Fed's target, but it also might significantly increase the stability of "main street" when it needs it so badly.

The Bottom Line:

When I (and others) feel uneasy about important economic policy issues, we are easily swayed by people who cherry-pick data, make their standard arguments, and are led to see things in as negative a light as possible.

As an undergrad, I heard that econ was highly quantitative and a course in simple probability would fulfill the requirement. That choice was good for teaching stats and research methods but I’m pretty sure I lost out in the long run.

Neither can the supposed “Globalists’ who meet in Davos and are the bane of critics on both left and right.

A point even conservative pundit Mark Theissen argued today (while still blaming Biden).

At the end of 2000, the Dow stood at just under 10,800. As I write this, it’s just over 31,000.

That’s not even considering the popularity of corporate stock buy-backs, which drive up the price of the shares and inflate the Dow.

Thereby benefitting shareholders.

Twitter celebrated Liz as the first prime minister in decades to span the reign of two British monarchs!

Let me take a proverbial "stab" at three of these questions:

Multinational corporations have changed the global economic landscape, but some think that we have entered a process, post-pandemic, of "deglobalization," at least to some extent. I would recommend the essay by Rana Foroohar in last weekend's edition of the Financial Times. It is derived from her book, Homecoming.

The Federal Reserve attempts to balance inflation and unemployment through its influence on the supply of money and credit. If unemployment is regarded as the primary macroeconomic problem, it eases up on the money supply in an effort to stimulate spending. This was the case in 2008 during the financial crisis, as well as in 2020 during the pandemic. Right now, inflation is regarded as the primary macroeconomic problem, so the Fed is tightening the money supply in an effort to restrain spending and mitigate the upward pressure on prices.

The quote that has been historically associated with Milton Friedman is, "In the long run, inflation is always a monetary phenomenon." This means that Friedman laid the responsibility for inflation squarely at the feet of central banks (monetary policy), and not governments (fiscal policy, which refers to government spending and taxation.) Fiscal policy can have an indirect effect on monetary policy if, for example, the monetary authorities take into account the degree of government borrowing when formulating their policy decisions. However, it is not the primary factor.

Economics has never made sense to me. The politicians can’t govern it, the economists can’t predict it—neither group can even manage it well.

I am middle-class. I feel 6 feet from economic disaster each day—it weighs on me and I am tired of it. I dislike our market-driven economy (which insists on exponential growth on a finite planet), yet I rely on this economy because I am immersed in it and must function by its rules. Worse yet, I subscribe to the ethics of a basically penniless carpenter who lived 2000 years ago—a fellow who had not a 401K or Social Security who went around saying we needed to help the poor (and we know what the state and the religious leaders did to him!).

I sometimes joke that economics is some sort of voodoo. I’d much rather try to solve a quantum mechanics problem than deal with economics.

(By the way, it is an election season though, and if you ask the right person, they’ll pronounce that inflation is caused by Joe Biden! Economics is clear during election season…)

Sorry for the rambling! Thank you again John, and God bless.