Transactional Higher Ed Is Here To Stay

Also, Seattle Pacific to cut its academic program by 40%!

Last August, I wrote about Wendy Fischman and Howard Gardner’s “The Real World of College”. Based upon a decade of research involving about a dozen schools, the found that many students come to college looking for what they can get out of it, namely, a job. As part of their research, they considered the reasons students had for attending college: Inertial (it was the next step); Exploratory (learning about stuff); Transactional (getting a good job that pays well); and Transformational (finding yourself and your calling)1. I wrote:

Fischman and Gardner happily found that only 3% of their students fell in the inertial category. But the largest category was transactional, capturing 45% of the group. This was followed by exploratory at 36% and transformational with only 16%. I should note that for seniors, the transformational percentage went up to 22% (the transactional was actually a point higher than the sample overall, likely due to the nearness of finishing and worries about job prospects).

That nearly half of all students, regardless of year in school, saw college as about jobs and future prospects underscores the argument Will Bunch was making in his book. We have told students for decades that a college degree was their ticket to a job (or more dire, that their prospects without a degree were extremely limited). It should be no surprise that they have taken those lessons to heart and approached college in a transactional way. It is credentialism at its worst and, as Fischman and Gardner argue, is responsible for the tremendous stress and anxiety experienced by today’s students.

The Fischman and Gardner book came to mind last week2 after reading stories that not only highlighted the transactional model, but took the added step of making it normative. First, I noticed on Twitter that a couple of people whose opinion I trusted had shared an analysis by Preston Cooper of the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity.

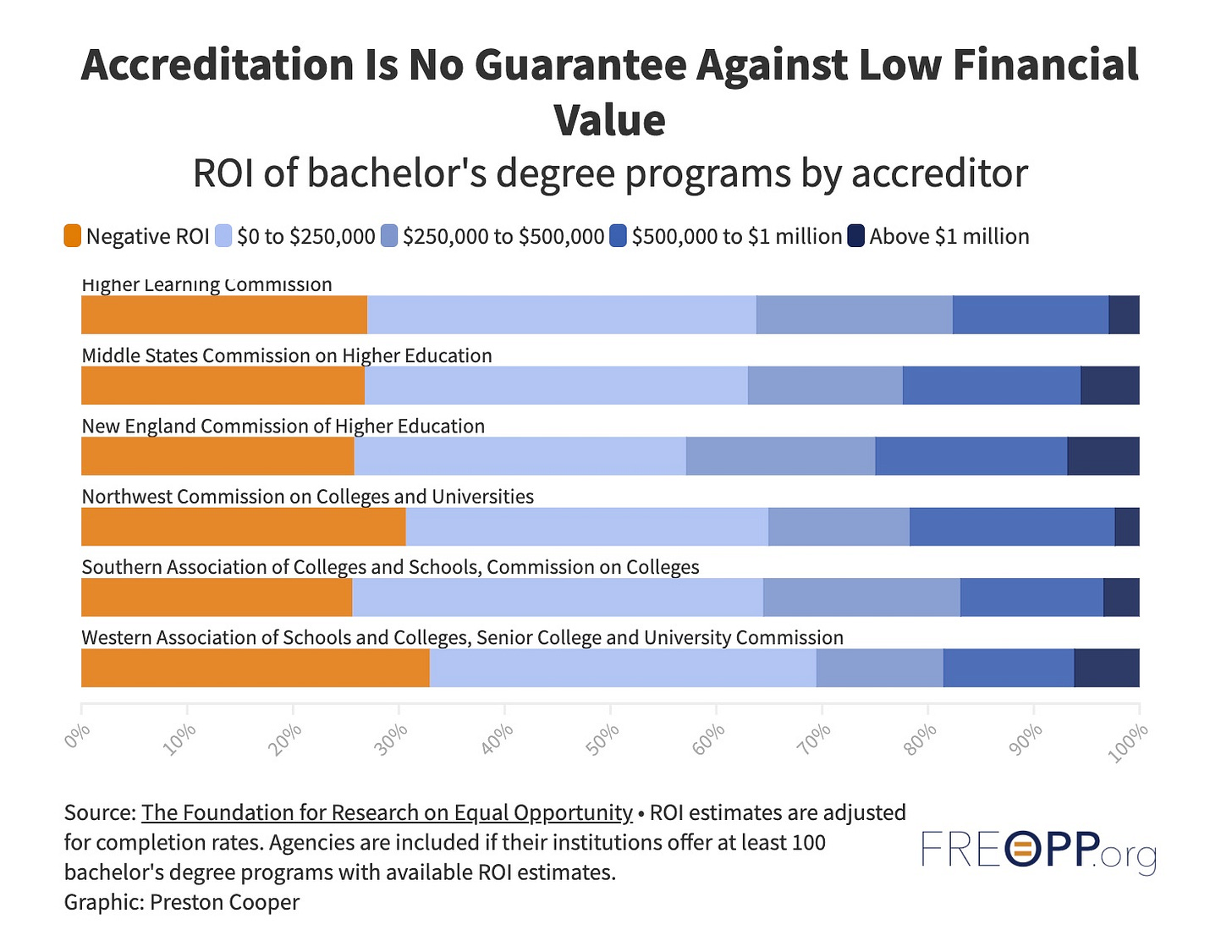

Cooper conducted a robust analysis of the “return on investment” (ROI) for various programs. To oversimplify a complicated analysis, he compares the lifetime earnings of graduates of various college programs (separated by degree level) against the counterfactual of them not attending college at all. So the costs of college (tuition, fees, books, room and board, living expenses) are charged against the median lifetime earnings.

The FREOPP ROI metric compares the lifetime increase in earnings associated with a particular degree to the costs of obtaining that degree, including tuition, time spent out of the labor force, and the risk of dropping out. If the lifetime increase in earnings exceeds these costs, that credential has a positive ROI and typically leaves students better off financially. If costs exceed benefits, the credential has negative ROI and students are typically worse off for having enrolled.

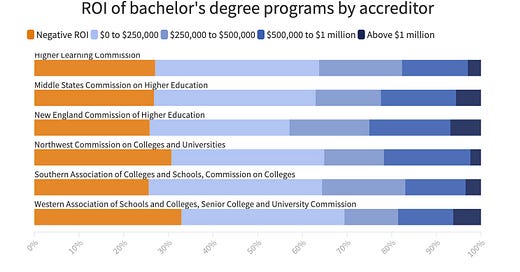

He argues that between 26% and 33% of programs at the bachelor’s level have a negative ROI. This certainly fuels the “Is College Worth It?” debates. The thrust of Cooper’s argument is that the accreditation agencies have failed to properly hold institutions accountable for continuing negative ROI programs. He includes the following chart:

As a Higher Learning Commission peer reviewer3, I have trouble reconciling the accreditation process with the model that Cooper suggests. Institutions are expected to have clearly stated learning objectives for every program offered (including general education and co-curricular programs) and have defined means of assessing how well students meet those objectives. In addition, institutions are to have a method for tracking graduates and evaluating employability. They are also expected to undergo periodic program review to determine what changes might be necessary for a program’s long-term success. Failure to meet these requirements result in an institution having to remedy those gaps and subsequently report on improvements in systems and outcomes.

In short, these requirements are designed to evaluate change in learning over time. In Fischman and Gardner’s terms, this is at least exploratory in nature but is hopefully transformational. If accreditors agreed that the transactional model was desirable, it would be possible to require programs to conduct an ROI analysis on a regular basis. However, the basis of peer review would be to assure that institutions have a means of evaluating program ROI. It would not fall to the accrediting body to determine which programs stay and which should go.

While I don’t think using the accrediting bodies is the best way to accomplish these ends (and am not convinced that these are the “right” ends), such an approach is gaining popularity not just among educational researchers but among government entities.

The Senate Republicans on the HELP committee4 put forth a number of bills5 that seek to reshape higher education. In addition to significantly limiting graduate loans6, they propose going after institutions without sufficient ROI. Beth Akers reports in a piece for the American Enterprise Institute:

And lastly, the package puts colleges on the hook in a big way. Historically, colleges pumping out batch after batch of graduates without the skills to earn a wage above that of a high school graduate could stay on the federal dole indefinitely; receiving grant funding and having their students eligible to take on massive levels of predictably unaffordable debt. One of the bills in this package (the Streamlining Accountability and Value in Education (SAVE) for Students Act) will bring an end to that nonsense by making federal student loans unavailable in instances where half of previous graduates at an institution haven’t been able to earn more than the median level of earnings among high school graduates.

Megan McArdle noted in today’s Washington Post that the bulk of student loan dollars, especially at the high indebtedness level, are associated with graduate degrees. Perhaps an ROI approach might be helpful for these programs. However, many small schools like those I served moved into graduate programs as a hedge against declining undergraduate enrollments. Take away funding and those programs will disappear, putting numerous institutions at serious financial risk.

The overall approach to ROI is now under consideration by the Biden Administration. According to Inside Higher Ed,

The Biden administration is proposing to calculate and report whether students can afford their yearly debt payments and that they are making more than an adult who didn’t go to college for all postsecondary programs with more than 30 graduates or completers.

While the current focus in on for-profit institutions, it’s not hard to see how this could be generalized to all institutions (especially under a Republican administration).

This institution-level focus on ROI is a natural progression from the cost-effectiveness approach causing institutions to significantly reduce, combine, or eliminate programs as I wrote last November. This week, Seattle Pacific announced that it was cutting its academic budget by 40% — an unfathomable percentage.

It is true that SPU has suffered enrollment losses over the last decade. Total enrollment fell from a high of 4270 in Fall 20137 to 3443 in Fall 2021. That’s a decline of 19.4% over eight years. Perhaps the Trustees are anticipating future challenges with the demographic cliff. It’s also possible that the Trustees are pushing back against a faculty unhappy with the Board’s recalcitrance over the last several years.

Like many institutions, SPU has gone through years of belt-tightening to deal with budget challenges. It’s not feasible that there is much fat left on the bone — certainly not 40% worth.

These cuts will hurt. Faculty lines will be lost. General Education courses might be seen as a luxury (they don’t show ROI!). Courses will be harder to get. Classes will be significantly larger. Recruiting new students and new faculty may prove more challenging (on top of the existing challenges).

In one of my administrative roles years ago, I was charged with another cabinet member to see how we could cut the budget by a large amount (not 40%). We went back to the president and argued that to make those cuts would start the institution on a cycle of decline that might be irreversible. No one actually knows where that tipping point might be. It’s likely only discovered in retrospect after the institution closes.

At the heart of all this is the pursuit of the wrong goals. If an institution, especially a faith-based liberal arts institution, pursues transformation in the lives of the students a very different ROI results. It might be more expensive but the transformative result certainly wouldn’t be the same as that of the student who didn’t attend college at all.

If, on the other hand, all we care about is a transactional ROI, our students will go to the cheaper state school following two years at community college and never darken the doors of the Christian Liberal Arts Institution.

[Note: I’ll be at the Mountain Sky Annual Conference on Friday so no newsletter that day. I’ll reflect on Annual Conference for Monday’s newsletter.]

My shorthand, not theirs.

This is the post I’d planned for last Wednesday.

In the past, I played a similar role for the Northwest Commission on Colleges and Universities and the Western Association of Schools and Colleges.

Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions

It’s unlikely that these bills will make it through the Senate. Bernie Sanders chairs the committee.

Even more amazing is that these cuts were made by an interim president and an interim provost!

Correlation is not causation, but 2013 was the year LGBTQ+ discussions began at SPU. It’s hard to know how much enrollment has been lost because of the public relations crisis resulting from the Board’s actions.

I teach at SPU. What your enrollment trajectory doesn't show is that each of those years leading up to around 2021 were smaller drops, whereas the declines from 2021 to 2022, and now going into fall 2023, are VERY steep. This confirms how badly the Board's (and interim President's) leadership over the LGBTQ issues has gone in Seattle, what with the constant negative PR, many lawsuits, everyone's morale being rock bottom: most progressive students don't want to come here, nor do many conservative students either. We're viewed as too conservative (given the policy), or too liberal given the majorities of faculty and students wanting change. The cuts will hurt, like cutting off limbs: it's not merely "Faculty lines will be lost", but 40% of those lines will be gone due to people leaving and them not being refilled, or altogether chopped. I fear we will not be able to recover, and thus I am applying for jobs, looking to other industries... and I think most faculty are doing that, having largely lost hope. What is insidious about this is (i) the leadership continue in their dishonest talking points saying this is due to national enrollment trends, being unwilling to acknowledge that keeping the policy and its many lawsuits has seriously undermined the institution; and (ii) the Free Methodist Church (which continues to have multiple FMC Board members -- including the Bishop who is still being sued, along with the interim President, for fraud over his conduct throughout these controversies!) stands to acquire the property, worth hundreds of millions of $$, if the institution eventually has to close. Talk about a serious conflict of interest. In the absence of proper communication and leadership from the top, we have begun to worry that they do not care, and might actually want, to sink the institution.

Thank you for sharing this information. Much of it I was unaware of. The title of your post is accurate. Thanks again and God bless.