It was a little over a decade ago that I became interested in how millennials were different from previous generations1, especially with regard to religion. National polling was discovering a tremendous increase in “Nones”, who had limited religious identification. Robert Putnam and David Campbell argued in their 2010 American Grace that society had experienced the earthquake of “the sixties” followed by an aftershock of the rise of the Moral Majority. They describe a second aftershock in reaction to the first, leading to the increase of the Nones among the youth. The next year brought David Kinnaman’s You Lost Me, an examination of why young people weren’t responding to religion in the same way as previous generations. It was Kinnaman that introduced me to the phrase “discontinuously different”, that I’ve always felt was a great descriptor of the moment.

This generational shift drove my research agenda for the next decade. I wrote a book for students of these younger generations as they considered beginning their studies at a Christian University. I argued that these generations were less institutionally focused and more concerned with connection with others’ stories. I did a content analysis of a series of millennial evangelical memoirs to document the ways in which these new expressions presented themselves. I gathered survey data on clergy in a conservative protestant denomination, contrasting the views of Boomers with Millennials. My current book project can be thought of as a clarion call for how Christian Universities need to reimagine themselves in light of these profound changes.

Not everybody shared my view. Reputable sociologists and religious leaders argued that this was no different from the institutional distancing all young people did in their late teens and twenties. Just wait, they said, until they marry and have kids and they will revert to previous patterns. This is known as a life cycle effect — everyone goes through similar stages in life even if on slightly different timelines (ages of first marriage and childbirth are older today).

My approach is what is known as a cohort effect — that these generations grew up in particular circumstances that shaped their understanding of the world. Central to that shift is the internet which allows us to connect with others different than ourselves. There are also important historic (or period) effects. For the millennials, it was 9/11. For Gen Z it was the 2008 financial crash. Those disjunctions from normal life have long tails — they change how we think of the world in the same way that the Great Depression did for the Silent Generation or the Space Race did for Boomers. One imagines that fifteen years from now we’ll be talking about the impact of the Covid pandemic on the generation following GenZ.

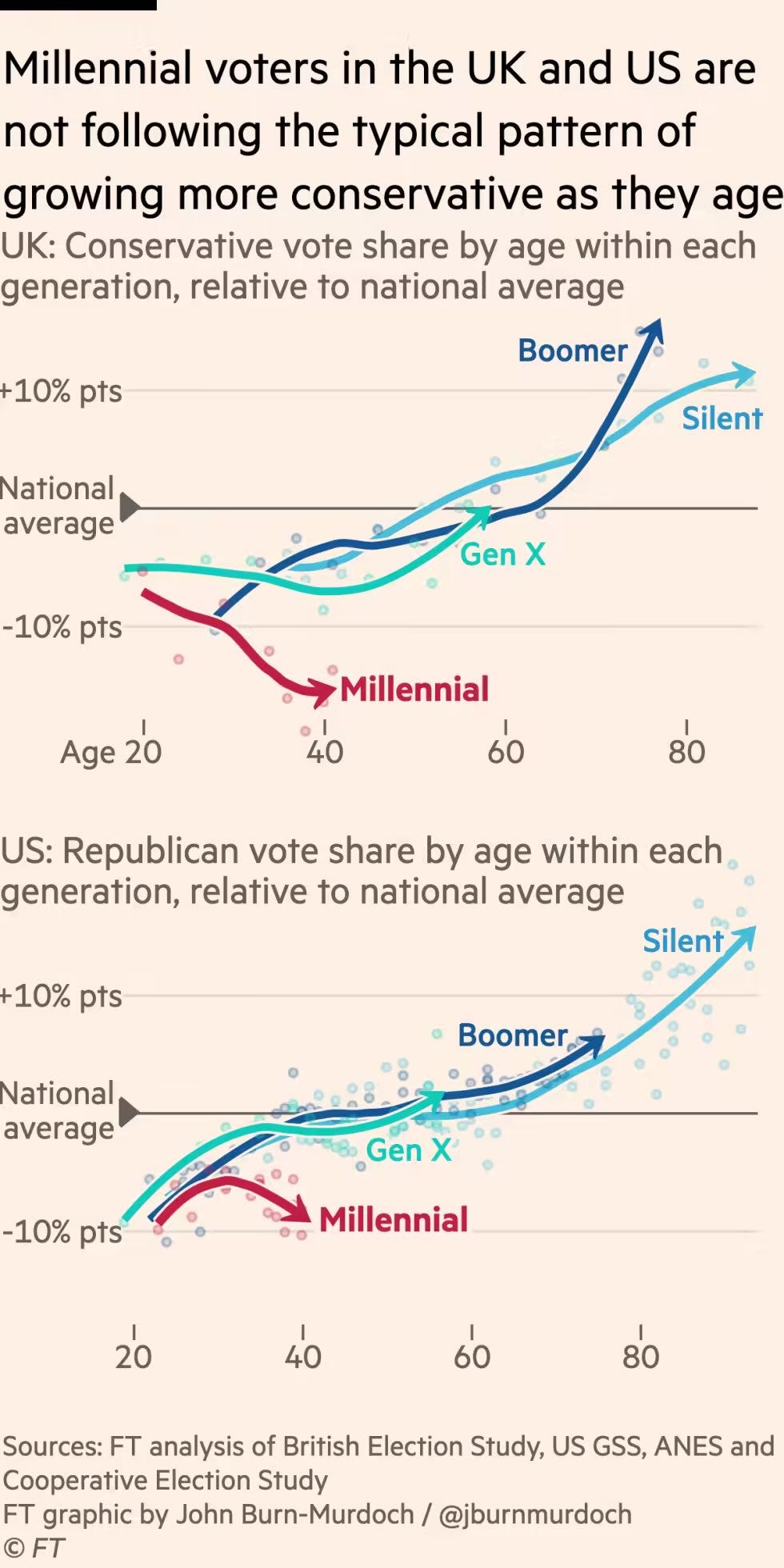

Last week brought new evidence to bear on the life cycle vs disruption question. In a Financial Times article titled “Millennials are shattering the oldest rule in politics”, John Burn-Murdoch documented the end of the life cycle theory. While previous generations had followed a similar pattern of growing more conservative as they age, this was not at all true for millennials.

He illustrates that Millennials2 in the US began to show voting patterns similar to previous generations but that pattern shifted markedly in the last ten years. The changes are even more dramatic in the United Kingdom. Early indications from voting in the 2022 midterms suggest an even greater shift within GenZ3.

When the story hit Twitter the middle of last week, there were a number of reactions that could be characterized as “well, duh!”. Will Bunch, of the Philadelphia Enquirer, observed that economic factors have made buying a home or marriage/family much more difficult while Courts were striking down assumed rights and threatening more. Pastor Ben Marsh had a long Twitter thread arguing that Millennials were no longer buying in to conservative talking points and political posturing.

I think that much of the disruption is explained by 9/11 and Iraq, the financial meltdown, college debt, and a job market that promises more than it can deliver. Add to that the deep concern these younger generations have for issues of diversity, rejection of intolerance, matters of justice, and, surprisingly, a desire for a more hopeful future. I would agree with Pastor Marsh that the younger generations don’t necessarily favor Democrats because there are policy initiatives4 that will address their concerns, but that Republicans seem unwilling to even acknowledge them beyond blaming the party in power.

This discontinuity is important, especially over the long run. I think about Robert Jones’ 2016 The End of White Christian America. In this important book, Jones — the former CEO of PRRI — describes how the rise of the Nones coincides with demographic transitions within the society. As members of the younger generations replace those from the Silent and Boomer generations who die5, the voting pool will be less dominated by White Christians (who make up a sizable percentage of the Republican voting block). This will have a profound impact on the political landscape.6

This is not likely to be a strictly linear process. There will always be young conservatives like those celebrating at Charlie Kirk’s TPUSA conferences. But I tend to see these are rear-guard, reactionary movements. Their popularity arises not from the fact that they are “winning” but that they are circling their wagons against the larger social and culture changes underway.

It is, of course, theoretically possible that the patterns that John Burn-Murdoch found are not a break at all but rather a simple delay in the previous patterns kicking in. It’s possible, but I find it unlikely. The sooner our political and religious institutions grasp the magnitude of the discontinuous difference, the better their chance of managing institutional challenges over the next decade.

Allow me to prebut my critics. I agree that Generational analysis is a crude tool and that there is as much variability within generations as between. Nevertheless, as a sociologist I’m interested in observing the general trends and not trying to overdetermine every instance. In that case, especially if we examine period effects, I find it worthwhile.

For the record, the Millennial generation now covers ages 27 to 42.

The members of GenZ are currently between 10 and 25. That means half of them were of voting age in November 2022.

Although the legislation enacted in the last half of 2022 might improve their views of Democrats over time.

A tough phrase for this Boomer to put in print.

One that, admittedly, will be limited by the structural barriers created by the Electoral College, the composition of the Senate, and actions of a conservative-leaning Supreme Court.