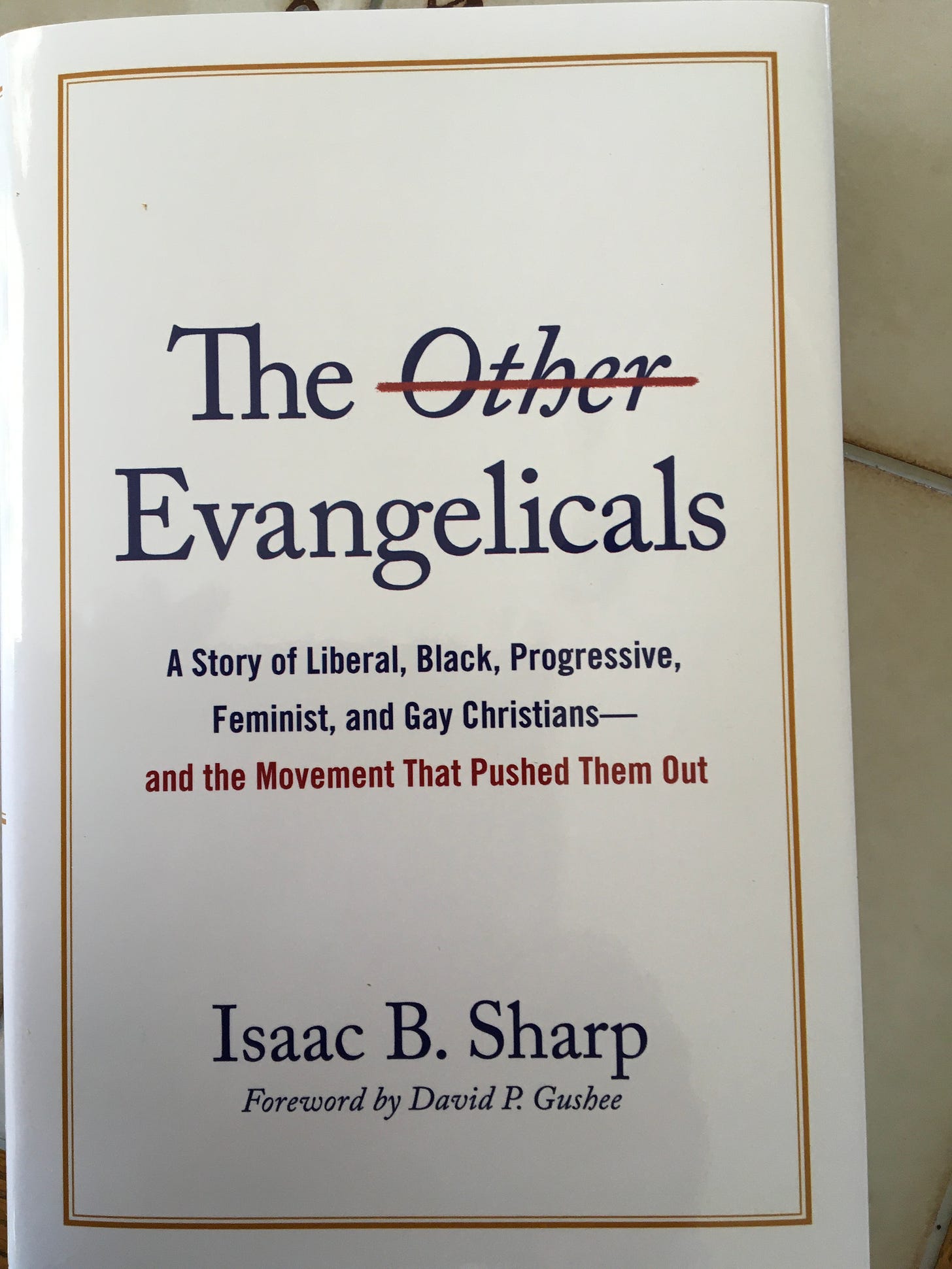

There’s a story I’ve told many times over the past forty years. I usually tell it as an illustration of how diverse parties in an organization can find a point of agreement. I was reminded of the story this weekend as I began reading Isaac Sharp’s The Other Evangelicals.1

Here’s the story: I began my teaching career at Olivet Nazarene University in Bourbonnais, Illinois. The main population center is the better known Kankakee, but adjacent to Kankakee is the city of Bradley and adjacent to Bradley is the Village of Bourbonnais.2 When I moved to Bourbonnais, the most recent Census count showed just over 13,000 residents (it was over 18,600 in 2020).

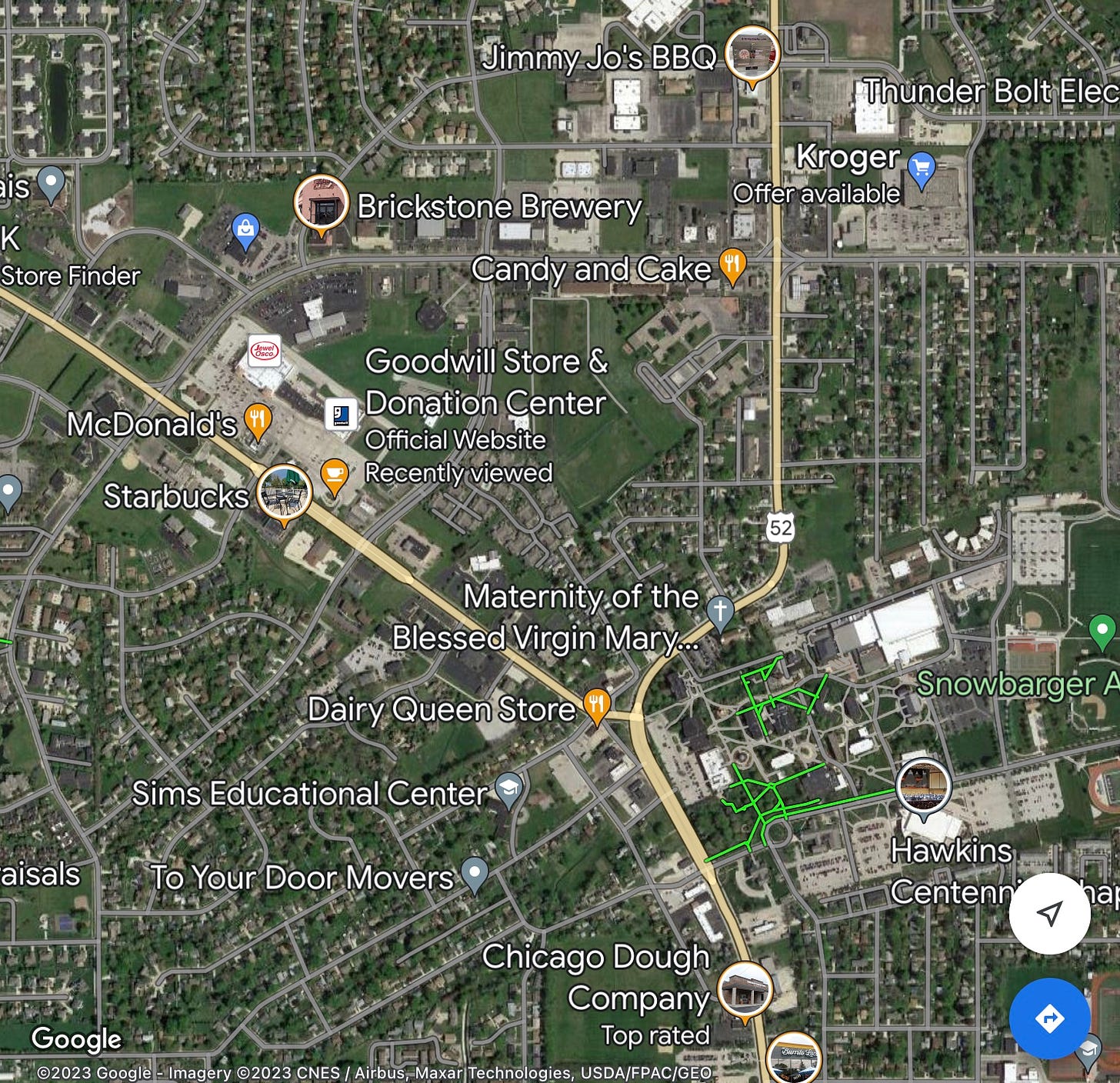

The village, such as it was, was spread out along two major arteries. The street that connected Kankakee, Bradley, and Bourbonnais ran by the university and then split into two roads, one heading North (highway 52) and the other heading Northwest (highway 102). Housing developments and strip malls characterized both arteries but there was little sense of “village-ness”.

Olivet is on the lower right of this map. The two arteries are clearly visible in the upper part of the map. Notice that there is a road running East from Bourbonnais (Armour road: right under the Krogers). It was the back way to get to Interstate 57 without going through town.

The village leaders had a great idea. They would extend Armour road to the west and then have it connect to Highway 102. And Voila! There’s a Village Center!

This cartological trip down memory lane came to mind as I was reading the opening chapter of Sharp’s new book. Here’s the relevant passage:

Because by staking a claim for a new identity space called evangelical, such leaders were simultaneously claiming the power to define evangelical identity however they saw fit. And if being an evangelical meant what they said it meant, then it is no small wonder that standard accounts, be they statistical, historical, sociological, or otherwise, have indeed consistently looked like the relatively small group of theologically and politically conservative power brokers behind flagship institutions like Christianity Today and the National Association of Evangelicals. By positioning themselves as the rightful heirs of the evangelical tradition, in other words, the leaders of the twentieth-century evangelical movement were able to secure their understanding of evangelicalism as the mainstream version. In so doing, their definition of evangelical identity became canonical (p. 23).

It’s as if the leaders of what is now evangelicalism pulled together their organizational structures like the NAE, Christianity Today, and Fuller Seminary (with uncounted numbers more since then) and said “here’s the center of the village”. Moreover, that assertion (that Sharp aptly describes as “canonical”) becomes the default. It’s a short hop from that to “the village center has always been here”.

By the way, Scot McKnight is also writing about the book on his SubStack. He concluded last week’s post like this:

To sum up let me put it this way: the theological culture war by some evangelicals today is phase two of the neo-evangelical gatekeepers. Their chosen battlefields are women in ministry, the sexuality controversies, and the not so-subtle but still less overt battle about racism as systemic.

As Scot suggests, the center of Sharp’s argument is that by interrogating the story of those who held evangelical beliefs but didn’t align on other issues, we find out where the boundaries of evangelicalism developed3. Historical criticism is out. Black evangelicals are welcomed as long as they keep racism as a sin matter and avoid structural concerns (sound familiar?). That these differences were not essentially theological but rather dealt with patterns of association or sociological understandings of the broader society, tells us a great deal about how evangelicalism is operationalized.

Once those boundaries become reified, all kinds of support entities develop (to push my metaphor, I think of the ball fields and green space in the center of the newly defined village). Kristin Kobes DuMez4 (who wrote a blurb for Sharp’s book) has been extremely important in helping us understand how these cultural artifacts help those boundaries stabilize. In Jesus and John Wayne, she writes:

White evangelicalism has such an expansive reach in large part because of the culture it has created, the culture that it sells. Over the past half century or so, evangelicals have produced and consumed a vast quantity of religious products: Christian books and magazines, CCM ("Christian contemporary music"), Christian radio and tele-vision, feature films, ministry conferences, blogs, T-shirts, and home decor. Many evangelicals who would be hard pressed to articulate even the most basic tenets of evangelical theology have nonetheless been immersed in this evangelical popular culture. They've raised children with the help of James Dobson's Focus on the Family radio programs or grown up watching VeggieTales cartoons. They rocked out to Amy Grant or the Newsboys or DC Talk. They learned about purity before they learned about sex, and they have a silver ring to prove it. They watched The Passion of the Christ, Soul Surfer, or the latest Kirk Cameron film with their youth group. They attended Promise Keepers with guys from church and read Wild at Heart in small groups. They've learned more from Pat Robertson, John Piper, Joyce Meyer, and The Gospel Coalition than they have from their pastor's Sunday sermons (p.7).

Here’s one other connection I made to Sharp’s book. Back when I was teaching sociological theory, there was always a lecture about Emile Durkheim’s Division of Labor in Society. He posited that all societies needed some form of solidarity that connected individuals to the larger social values. He further argued that there were two basic forms that solidarity could take: Mechanical Solidarity or Organic Solidarity.

Mechanical Solidarity has sameness as its organizing principle. Leadership and authority are hierarchical and maintaining boundaries is crucial to group stability. Any act of deviance results in expulsion from the group at best and death at worst. The boundaries lie wherever they need to for group maintenance.

Organic Solidarity (referenced in his title) is based on difference. In a complex society, interdependence is key. Each organization, institution, work group, must work effectively with others for societal success. When someone violates norms, the society strives to restore people to correct behavior rather than exclude them; precisely because they are needed for the whole.

In many ways, the crisis of evangelicalism over the last two plus decades reflects Durkheim’s contrast. If one’s viewpoint doesn’t properly align with the evangelical boundary, exclusion is the only response.5 Diversity of thought is otherwise a threat.

I may explore the implications of Organic Solidarity for evangelicalism in a future newsletter. For now, let me just observe that the diversity of views present on topics like race, LGBTQIA+ affirmation, politics, gender roles, and Christian Nationalism makes sense within that framework.6 Because working together effectively far outweighs boundary maintenance, a more collaborative response is needed.

I’m only a third of the way through The Other Evangelicals but it’s already compelling reading.

The official publication date is April 18th, but mine came last week.

The village has used the French pronunciation since its centennial in 1975 but long term residents called it Bur-Bone-Us.

Sharp has a remarkable passage where he describes how Gallup polling “created” evangelicals as a block. This trend has continued without much more nuance than existed in 1976. There is an amazing example of social desirability in some questions. For example, 47% of the respondents (not just evangelicals) claimed that they had witnessed to someone about their faith. Call my cynical, but that figure is remarkably high.

I’m looking forward to seeing Kristin this weekend in Colorado Springs. She was supposed to make a presentation there in February when I was on my accreditation visit but bad weather in Michigan kept her away. So everyone else’s inconvenience turned out quite well for me!

It’s why in 2011 John Piper tweeted “Farewell Rob Bell”

It’s also important that the democratization of our social media instruments allow those diverse perspectives to find voice where they wouldn’t have in earlier periods.

I may have to read this book, too. Helpful context/comments, John! Thank you.