This is my final newsletter (at least for now) prompted by Will Bunch’s excellent After The Ivory Tower Falls. Bunch describes the social separation that has happened between those who went to college and those who did not. He further separates those groups into those who came of age before 1990 and those after. For the non-college group, the before 1990 folks he calls the Left Behind; the subject of Monday’s newsletter. Today we look at the Left Out, those who came of age after deindustrialization but lack the college degree society demands as a credential.

Here is Bunch’s description:

The broader profile of this new, lost generation of America's undereducated is not an especially political one. In looking at how "the college problem" has sliced and diced America into different social groups, I came to consider these noncollege young adults as The Left Out. Despite the growing crises they face, no one is really advocating for political action on their behalf, even as some leaders focus on student debt and the problems of those who'd gotten further along in their schooling. Of course, politicians feel fairly free to ignore this cohort because these young people tend to vote in relatively small numbers. Atomized and increasingly antisocial, millions of The Left Out are essentially off the grid (185-186).

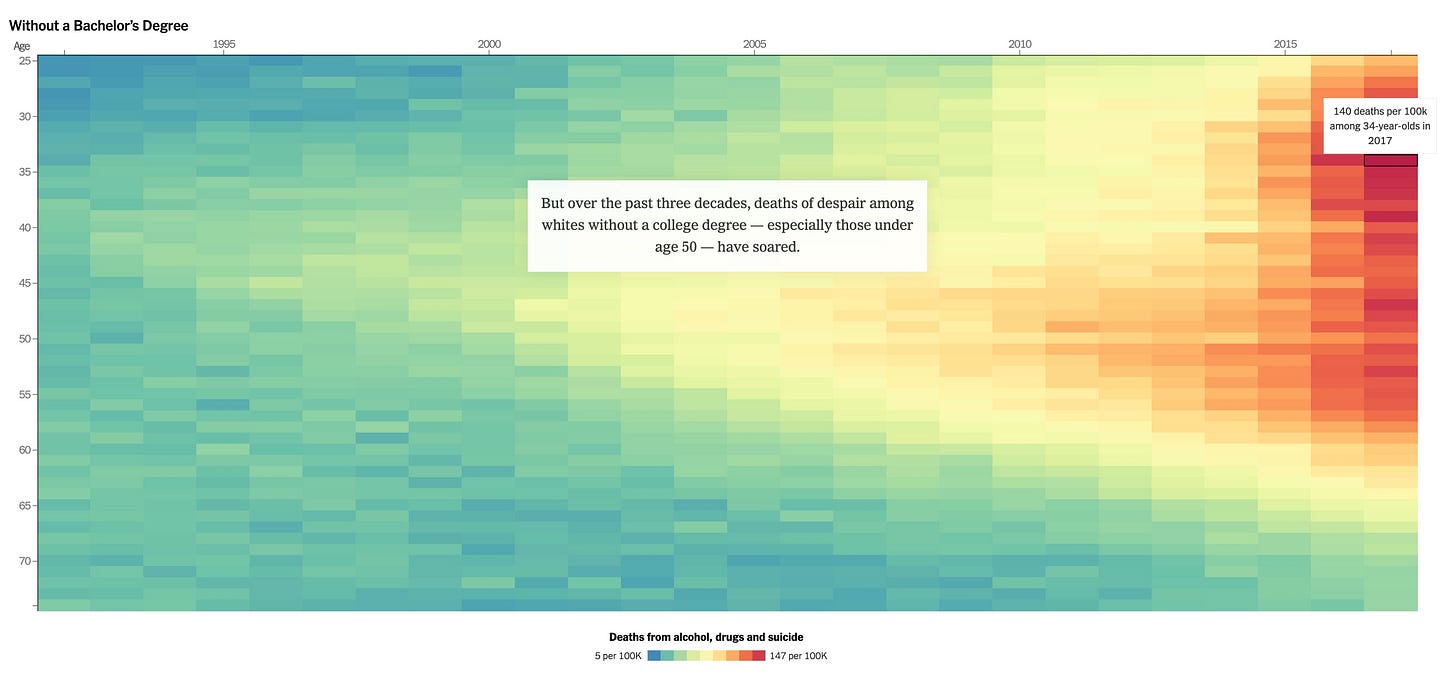

He cites research by economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton that shows how “death by despair” has impacted the non-college educated crowd. In 2020, the New York Times illustrated the Case-Deaton hypothesis with an interactive chart showing impacts by age group over time. This is a screen shot from that chart.

This chart has time across the horizontal axis at the top and age running down the vertical axis on the left. The measure is the amount of death by alcohol, drugs, or suicide by age and time (per 100,000 population). As you can see, the upper right corner, recent data among young people, is bright red showing what ought to be a high level of concern among policymakers. By way of contrast the homicide rate in the US in 2019 was 5.0 per 100,000, an issue that generates lots of press and political coverage.

Not only have we seen the impact of deindustrialization and the concentration of resources in urban and suburban areas, we’ve seen a shift in how we think about adolescence and adulthood. For several years, I have followed the work of psychologist Jeffrey Jensen Arnett1 and used his Emerging Adulthood in classes. He argues that the late 20th century brought on a distinct developmental stage that he calls Emerging Adulthood. Factors such as delay in marriage, college attendance, decline of manufacturing, and “finding oneself” combine to create a life stage that didn’t exist in the 1970s. He says that this life stage is focused on five things:

So, what are the distinguishing features of emerging adulthood in the United States? What makes it distinct from the adolescence that precedes it and the young adulthood that follows it? There are five main features:

1. Identity explorations: answering the question "who am I?" and trying out various life options, especially in love and work;

2. Instability, in love, work, and place of residence;

3. Self-focus, as obligations to others reach a life-span low point;

4. Feeling in-between, in transition, neither adolescent nor adult; and

5. Possibilities/optimism, when hopes flourish and people have an unparalleled opportunity to transform their lives (9).

I really enjoyed using Arnett’s book in my college classes and the students really seemed to resonate with the argument. But I realize the same argument that works for college students might operate very differently for the folks Case and Deaton were studying.

I’d argue that there is a great deal of variability in the forces Arnett describes when it comes to the Left Out. Identity exploration, for example, is harder when your social circle still involves your high school crowd2. You are known by your past. The instability that is positive for college students may be more negative for the left behind, shaped by changes in the community, law enforcement encounters, or family crises. The self-focus and in-betweenness may still be there but in muted form.

It’s that last characteristic of Emerging Adulthood that I think is most critical for the Left Out: possibilities and optimism. What does a non-college, small town or inner city emerging adult think the future holds? Can one imagine a future that allows one to chase dreams, upward mobility, creativity, and fulfillment? Or have the economic and social changes rendered the future to be nothing more than an ongoing repetition of the present struggles?

I’ve reference Brian Alexander’s excellent Glass House in several of my recent pieces3. I want to give it more attention here. Alexander grew up in Lancaster, Ohio, home to the Anchor Hocking Glass Factories. The primary narrative of the book tells the story of how the plant, which was central to the community's well-being, fell victim to the leveraged buy-out, debt-loading, hedge fund practices beginning in the mid-1980s and eventually resulting in bankruptcy in 2015. It's a sad tale of how the financialization of our economy shifted resources to the big guns on Wall Street without consideration of the direct negative impacts on Main Street.

Alexander has a secondary narrative as well. Throughout the book, he provides updates on the lives of two young men born a year apart in the late 1980s.

When we first meet Brian Gossett, a fourth generation Anchor employee, he works the floor at the plant cleaning up debris from the production process. He eventually become an operator in Plant 1.

Plant 1 was so decrepit it had a reputation around the industry for being a "shit hole." Brian dreamed of one day leaving the shit hole. He'd never intended to be a glassman. He wanted to be an artist. He looked a little like a beatnik artist, too, with his neatly trimmed blond beard, his short blond hair, and those horn-rims. His mother had inherited a house on East Main Street, practically next door to a dive tavern called Leo's Bier Haus, and though the house itself was destroyed by a fire and the lot sat vacant, Brian and his parents had a deal. He'd keep the lot mowed and at least a little tidy. In return, he could transform the upstairs room of the antique wooden garage in the back, by the alley, into a studio. The studio was tiny, a low-ceilinged room with a floor that sagged alarmingly to the west (8).

Over time, the financial problems at the plant made Brian take a job he didn’t enjoy in a nearby town. He eventually got on with his art, living a somewhat off the grid existence. Here’s how we see Brian at the end of the book:

So it wasn't just the poor or the working class who felt disaffected, and it wasn't just about money or income inequality. The whole culture had changed. Brian was from a middle-class family, but he didn't believe in any institution or person in authority. He didn't feel like he was part of anything bigger than himself. Aside from his mother and father, and his brother, Mike, he was alone (293).

When we meet Mark Kraft, one year younger than Brian, it is in the context of his drug use. A run-in with a teacher back in high school had put him off the academic track and he works for his parents’ small business. He travels with other users and eventually has a run-in with the Lancaster Major Crimes Unit.4 After a short stint in jail and probation, he goes to rehab. Earlier, Alexander writes:

Mark wished his life had more substance, though he wasn't sure what he meant by that. Maybe "fulfillment" would be a better word, but he wasn’t sure about that, either. When he tried to think of a form fulfillment night take, aside from drugs, he couldn't conjure an image in his mind. He knew that people sometimes claimed to be fulfilled, or said their lives were imbued with passion, but he was unable to step into the shoes of such people. They existed in a fantasy world. He could see them through the glass screens of his smartphone, his computer, his television. They were all far more glamorous and altogether happier than anybody he'd ever known. Mark's world was Lancaster, and America as seen from Lancaster — and in them, with the exception of his own family, there was nothing deserving of his faith. Nobody inspired him. He didn't think this situation was uniquely unfair to him: He imagined himself treading water, kicking his legs harder and faster to barely keep his head above it, but everybody he knew was stuck in the same water, treading just as furiously as he was."The world's stacked against everybody,” he said. That didn't make him feel any less lonely, though (207).

As upset as I am about the way that the financial vultures destroyed Anchor, and thereby Lancaster, my heart breaks for Brian and Mark. Where is their hope? What do they have faith in?

Alexander cites an article by conservative critic Kevin Williamson in which Williamson argues that people should simply pack a U-Haul and leave their little struggling town. But Lancaster is home to Brian and Mark. It shaped them and forged their identity for good or for ill.

I’m searching for a happy ending to this piece, a clear policy initiative that would address the needs of the Left Out. But I’m at a loss. We can decry the drug use, overdoses, alcoholism, poor health, crime, and poverty of these people. But what will we do about it?

We have allowed the hollowing-out of small-town and inner-city America and are now paying the price in health crises and too-early deaths. One would hope that two years of confronting death and loss on a daily basis would make us more compassionate. Sadly, we’ve left too many people stuck on a treadmill that doesn’t lead anywhere.

Disclaimer: Arnett wrote a very nice blurb for the back cover of my book

A favorite narrative trope that carries real power is that of the high school star athlete trying to reconcile past fame with current mundane reality. Think of Updike’s Rabbit series of HBOs Mare of Easttown.

His follow-up book, The Hospital, is equally good. His reporting on small town economic challenges provides some great sociology.

Why Lancaster, Ohio, has a Major Crimes Unit is beyond me.

Good, but sad, post John. Your last paragraph says it all. The hollowing out has resulted, I suspect, in a drop in tax revenue which hurts the local infrastructure--like public schools. Then those students are less prepared to go to college, etc.

Thanks again for the post.