I first met Seattle Pacific sociology professor Jennifer McKinney in 2014 at the Society for Scientific Study of Religion meetings in Indianapolis. In my presentation, I was contrasting evangelical institutional boundary setting with a testimony-based narrative. It was the early days of what became my millennial evangelical memoir project. I explored the differences between Mark Driscoll’s “Confessions of a Reformation Rev”1 with Addie Zierman’s “When We Were on Fire”.

Her presentation later the same day was on early content analysis she had done around online comments of former Mars Hill members. As we talked, I learned that she was a fellow Purdue Sociology PhD (Boiler Up!), although we missed each other by about a decade. I had the pleasure of speaking to one of her classes right after I retired and we maintain periodic contact over issues in Christian Higher Ed in general and SPU in particular.

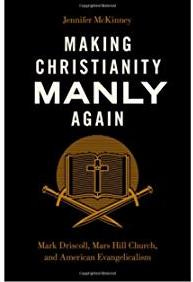

Because of this past connection, I was thrilled when Jennifer’s book on Mark Driscoll and Mars Hill came out recently. I finished reading it this weekend and highly recommend it.

Wait, you might ask, wasn’t there a whole podcast series on Driscoll and Mars Hill? Do we really need another look at what happened? The quick answer presented in Jennifer’s book is, of course we do. Because her book does many things that other excellent approaches have not.

For one, she puts the role of gender relations at the center of the Mars Hill experience. The misogyny present is not an unfortunate by-product. It was the brand. Who better than a gender sociologist to be able to unpack what happened at Mars Hill?

For another, she does a deep dive into content analysis. First, into Driscoll’s various sermon series and writings.2 Second, she uses interviews and online sources of Mars Hill members — those who loved it and those who couldn’t stay — to demonstrate the real world impacts of the Mars Hill masculine ideology.

Driscoll built the brand around the strong man imagery he felt was missing in Seattle. He critiqued modern men as “Cabriolet-driving, sweater-vest-wearing, Spice girls-singing wusses.”3 The Bible, according to Driscoll, required tough guys who like UFC and were willing to take strong stands for the faith. This would be the counter-cultural image that would change Seattle for Jesus.

If strong men were key to Driscoll’s vision, where does that leave the women? The quick answer is “at home with the children”. Beginning with a strong complementarianism that mandates male control, women must be in proper relationship — respecting their men, staying attractive, being sexually available. No two-working parents for Driscoll. Many families followed his strict advice regardless of the personal pain it caused.4

Jennifer’s interviews with Mars Hill families are heartbreaking. Many were attracted by Driscoll’s “solving the men crisis” approach. As the Christianity Today podcast series illustrated, young people were drawn to the church by Driscoll’s outrageous style and approach to a black-and-white scripture (according to Mark). They tried to adjust to his idealized models for masculinity and family. But it never quite seemed to work. They more they became like Mark, the unhappier they became.

Many of them left Mars Hill for other churches. I worry about the many others who thought “if this is Christianity, I’m out!”.

Jennifer’s book is good sociology. Not just on the family and gender stuff but in terms of our larger understandings of religion and culture. I had several questions I’m pondering after finishing her book.

In my own analysis of Driscoll’s memoir, I was struck by his lack of church experience. He was remarkably young when Mars Hill started and had never been on a church staff. Nevertheless, he felt he had the answers. But Driscoll’s answers were largely an extrapolation of his own personal story. He and his wife Grace wrote a book on marriage that largely reified their own marriage as normative for all. His sense of being masculine was generally a reflection of his own lifestyle preferences. Yet others were expected to fit that model. So while he was charismatic5 (in the Weberian sense), his lack of a healthy church culture kept Mars Hill from dealing with his dysfunction.6

If Mars Hill was supposed to be countercultural (in contrast to his imagined version of the local culture), what impact did it have on Seattle? Did people in the church impact the city in general by modeling their masculine Christian commitments? Or did anybody in Seattle care? Certainly, the negative press as Mars Hill was imploding would have had the opposite effect.

It occurred to me as I read the last chapter that Mars Hill was a sect-life organization (in Troeltsch’s formulation). Even though it boasted tens of thousands of members, it maintained an insular focus. The world out there was wrong. Only those of us in here know the Truth. Challenge that truth and you don’t belong.7

As I read the book and Driscoll’s views of masculinity, my mind kept drifting to the movie Fight Club. It felt like Mark loved the movie but missed the reveal at the end that Tyler Durden (or Edward Norton) was mentally unwell. This fits the ongoing “crisis of men” trope but never really deals with what healthy masculinity looks like. If you removed Driscoll’s approach to scripture proof-texting that he uses to defend his masculine superiority, you’d just have Josh Hawley’s book. At the end of the day, I fear that the men who bought into the Mars Hill brand are just as damaged as they were before they ever met Mark Driscoll.

Oh, and just in case you thought the Mars Hill experience chastened Driscoll, think again.

Read Jennifer’s book if you want to understand more about the impact of this kind of hyper-masculine Christianity.8 It will upset you but it’s important if we are to model a more humane Christianity that isn’t conflated with a host of other ideologies.

Hey, I got through this whole newsletter and managed to avoid that TGC article!

My eyes still burn from studying that book.

I imagine Jennifer has even more Driscoll PTSD than I have.

Having lived in the Pacific Northwest for over a decade, this image is hard to reconcile with the flannel-wearing, bearded, lumberjack-wannabees that proliferate the region.

Mars Hill maintained a hierarchical structure even more rigid than Driscoll’s default complementarianism. Challenge the ethic and you find yourself on the outside of the Mars Hill community.

He became famous when Don Miller’s Blue Like Jazz described him as “Mark the cussing pastor”.

Here’s another shout-out to Scot McKnight and Laura Barringer’s A Church Called Tov.

My dissertation was on people who regularly attend church but never join. That is difficult to maintain in a congregation so clearly built around insiders and outsiders. I found that this wasn’t completely true because congregations were willing to accommodate quite a bit to keep people in the pews.

Here’s another shout-out to Kristin DuMez’s Jesus and John Wayne.

I thought the "F" stood for fighting, since the article was about manliness. And in our culture manliness requires fighting at some level.

I recall my dad, when I was quite small, listening to a boxing match between Ali and Frazier that was broadcast on the radio (was it the "Thrilla in Manila" I wonder?). Later when I actually saw a match on TV I wondered why people were fascinated to watch two grown men pound each other. It was pretty distasteful.

Mr. Driscoll, in his message above in your post, is anxious to campaign against LGBTQ etc. I wonder why he doesn't announce a fight against homelessness? Against poverty? He has a platform, so why not fight for a universal basic income, for medicare for all -- these are things that (in my opinion anyway) Jesus would would resonate with. Now that would be manly!

The Prince of Peace is the manliest man who ever lived.

Thanks again John! You always make me think. God bless!

Thank you once again John for educating me. I know of some Mars Hill debacles, but few details about them.

I like to think I'm a manly-man, but I don't know what UFC is. (I think I'm glad about that.)

God bless!